Nothing sad happens in the opening fifteen minutes of Hayao Miyazaki’s eighth feature film Spirited Away. Nothing really even happens until the very end of the opening, where a traumatic event occurs to our protagonist that will change her life forever, but it does not and is not meant to inspire grief. So why, exactly, do I always find myself tearing up whenever this film simply does what all movies do and begin?

The reason why is because to watch Spirited Away feels like a special gift. It is a film of such startling imagination, originality, intelligence, and emotion that I feel inexplicable joy when the opening title card fades in as Joe Hisaiashi’s rapturous score starts to play. There’s the oft-debated difference between the “favorite” and the “best”. I already mentioned that Kiki’s Delivery Service is my personal favorite of Miyazaki’s filmography, as it is his most delightful film and the one that most resonates with me on a very personal level. There’s no doubt in my mind, however, that Spirited Away is his most remarkable accomplishment, and his best film in general. To see this film is to be transported to a world you can not find anywhere else, and I feel simply overjoyed whenever I have the chance to watch it again.

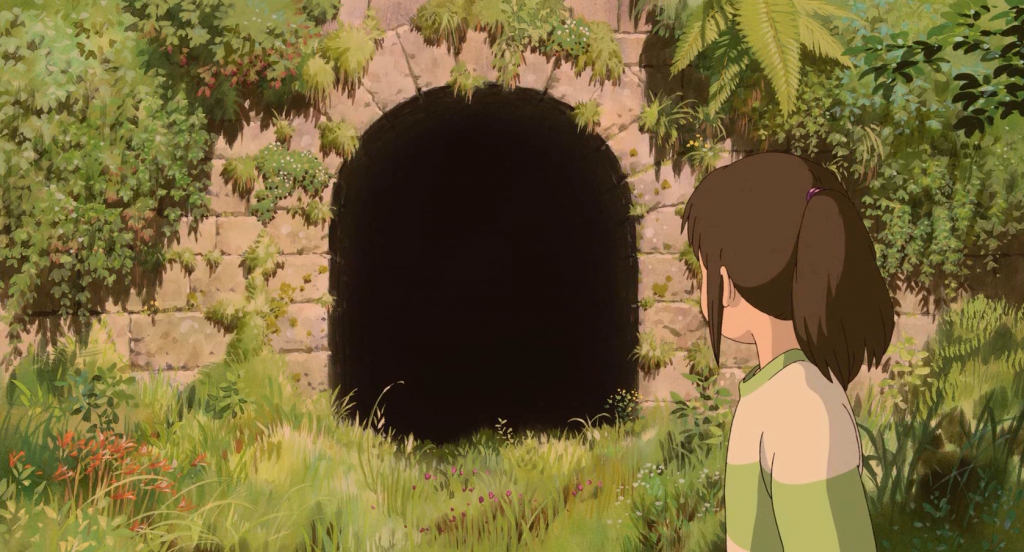

The film is–what else?–a coming-of-age story centered on a young girl named Chihiro, who’s really bummed out about moving to a new city where she won’t be able to be with her old friends. Her mother and father, who mean well but still shrug off her depression, are ready to move into their new home when a wrong turn on the road leads them to a mysterious, abandoned theme park. Or so they think. It turns out that the family has stumbled upon a passage to the spirit world, with Chihiro’s parents transformed into livestock after unknowingly consuming the food of the spirits without permission. Frightened and utterly alone, the only way for Chihiro to survive in this strange new world is to toil and work herself raw in a bathhouse run by a wicked sorceress.

It’s a story rife with familiar influences, from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland to Japanese folklore and, of course, Studio Ghibli’s now expected coming-of-age elements. But never has a film been so visually alive and imaginative that you can’t recall anything else like it. And still, to this day, unlike most other visually revolutionary films, its singular style has still not been ripped off after a decade. And how can you? There’s always been instances of strangeness in Hayao Miyazaki’s visuals (and this becomes broader when we take into account the other Ghibli films he didn’t direct), but Spirited Away is, visually speaking, his most unapologetically weird.

Not a single idea regarding this film’s world and characters feels borrowed or repurposed. Just when you think the film couldn’t possibly top itself with an impossibly, beautifully strange image, it gives you something more: the ferry that holds within it colored sheets with eerie paper masks over their heads, the overweight radish-person, the old man with multiple arms that can stretch to any length he wants, the giant duck thing that’s there for no reason, that iconic No-Face with his vacant mask and ominous black presence, the stink god made up of the pollution of the rivers (which brings up Miyazaki’s prominent theme of environmentalism), a lamppost that hops around on a single disembodied hand…I could go on for another paragraph if I wanted.

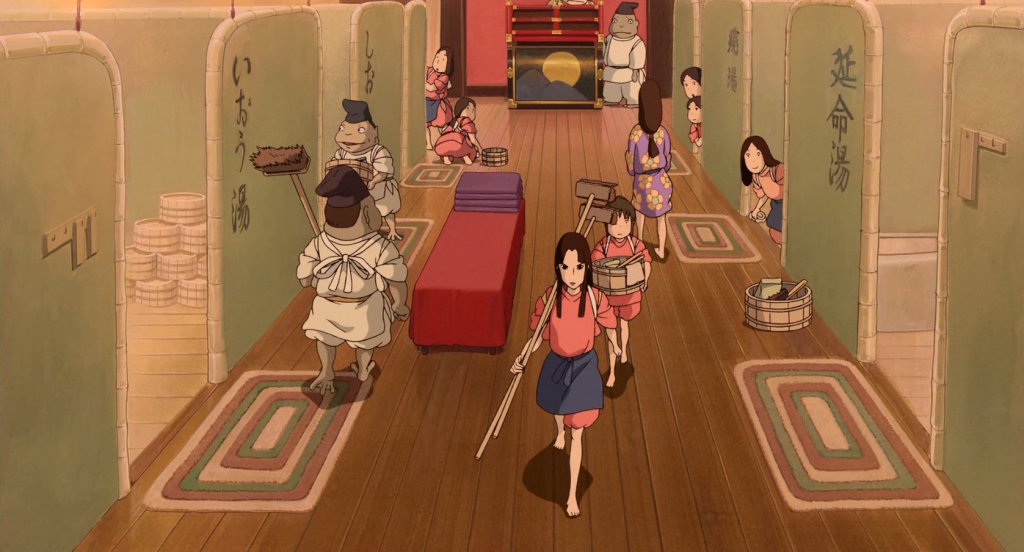

And it’s all contained in this immaculately drawn and delightfully mysterious bathhouse, a perfect backdrop for this cavalcade of delightfully bizarre spirits, which Miyazaki has stated in interviews was inspired by an actual bathhouse in his childhood hometown that he imagined to be haunted and contain a multitude of secrets. The bathhouse of Spirited Away, despite being only one building, is itself a whole other world, and not just because of the strange spirits that inhabit it. Its design is so meticulous and fully realized: stairways with no railings pose imminent danger; elevators are strung up to a multitude of floors that suggest that the building is bigger on the inside than out; secret compartments allow employees to send messages to the crazy old spider-guy who lives in the furnace; and even more details that don’t necessarily need to be in the movie, but further envelop the viewer in its surreal dimension.

Watching Spirited Away for the first (and perhaps second and third) time, it’s so easy to lose yourself in Miyazaki’s spirit world that it becomes even easier to ignore, or at least underappreciate, not just the beautiful simplicity of its story, but how within that simplicity is packed a multitude of themes that run the gamut from psychological to sociological.

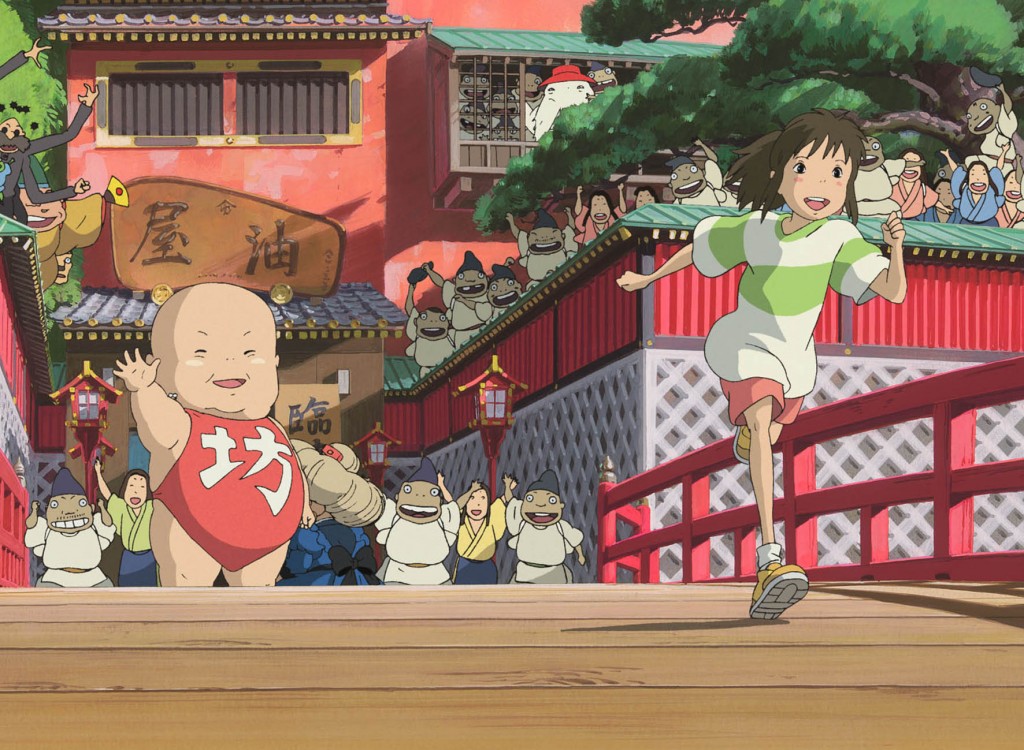

The main conflict we get here is Chihiro’s journey to escape the clutches of Yubaba the sorceress, bring her now transformed pig-parents back to their original selves, and escape the spirit world. Along the way, she learns to mature and come of age, which should be enough for any reader regularly following this retrospective to give a resounding “Duh!” because Miyazaki. But the real detail of interest here, one simple detail that contains a multitude of meanings, is how Chihiro’s coming-of-age is also a quest to preserve her identity.

Upon agreeing to work in Yubaba’s bathhouse, the sorceress literally steals Chihiro’s name and changes it to “Sen”. This is revealed to be how Yubaba imprisons people’s souls to working in her bathhouse forever: she steals away the identities of her workers and gives them more suitable names. These names tend to be more simplified–Sen, Haku, Lin, to name a few–thus sucking away the instances of verbal personality in them for something that is more functional and quick to say/write. Once your name is stolen, you slowly lose your memories of the person you once were, which will be important for Chihiro as she must be true to herself in order to escape this alien world.

I have seen Spirited Away countless times ever since it released on DVD and aired somewhat regularly on Cartoon Network for a couple of years. I know this film by heart, and have seen both the Japanese and (terrifically directed) English dub multiple times. But it wasn’t until rewatching the film for this retrospective that I finally decided to look beyond its sumptuous surface and find a web of ideas that I had never even thought of before lurking underneath.

Namely: Spirited Away is actually a workplace drama.

When you get right down to it, once Chihiro/Sen has started working at the bathhouse, while her concerns of escaping are always her primary goal, new conflicts arise to accommodate to the strange new rules of not just the spirit world, but of the workers’ world. Chihiro is chastised and harassed by her superiors because she is a human, so she experiences racism firsthand. She and her female coworker Lin are mistreated by their male coworkers, so there’s not only sexism, but even implications of sexual harassment as they make catcalls to the ladies.

All the while, each of the workers–male or female, spirit or human–have been robbed of their individuality, each one reduced to a homogenized resource by way of giving them all similar appearances. Not just in uniform but in physical structure too, as most of the males have deformed, large, frog-like faces, while the women are overly slender and shiny like stretched up putty.

In other words: similar in essence to any regular old workplace in real life, the only difference being the fantasy elements. In a way, the bathhouse of the spirits is like some kind of mini-dystopia, not just in how it depicts a society in which the workers are content but unfulfilled as they’re forced to literally serve and pleasure the gods, but also in how it connects these themes to very real problems in our current workplace society. How I had never picked up on these themes is a testament to how fully Spirited Away engrosses you into its fantastical world.

These themes truly come to life with the character of No-Face, a semi-transparent spirit with no real discernible form and whose only defining feature is a vacant, creepy mask that’s almost expressionless (pay close attention to how the mask is animated and see how subtle the difference is between its smile and its frown). If the various bathhouse workers are like a spiritual proletariat, then No-Face is representative of the lowest of the lower class. Deprived not only of a name but even a corporeal identity, he’s never allowed inside the bathhouse, as if he were a vagrant. The real reason why, however, is that No-Face’s power comes in mirroring the wants and desires of those around him, thus why Yubaba isn’t keen on letting him in–he’d only expose her and her workers’ greed. Y’know, like every time the poor comes face to face with the upper class.

So yes, Spirited Away is a coming-of-age film, like so many Studio Ghibli movies are, but it’s one that holds very real and potent problems found in the adult world, transferred into fantasy, and experienced by our child character at the young age of ten. Except here, Miyazaki evolves his theme of innocence into something more: not just as an intrinsic part of the human spirit, but also an intrinsic part of human identity. Spirited Away is just as much about the adult world’s continued efforts to sand off that identity as it is about preserving it.

This theme culminates as two of the greatest scenes Miyazaki has ever created.

The first is the film’s now famous train sequence (sadly not available on YouTube in a good enough quality), a lengthy stretch of the movie that has no dialogue and relies solely on mood and music, but boy is it the most melancholic thing Miyazaki had ever animated (that is, before he conjured up the ending of The Wind Rises). Chihiro, in order to save Haku, must travel all the way to a faraway swamp by way of train. This scene should and very well could have been just a simple segue from one plot point to the next, but Miyazaki transforms it into something powerful.

The train tracks are submerged underwater, making the train appear as if gliding across the ocean. Inside the train are a bunch of spirits, each of whom are faceless and never speak. Chihiro, the now-friendly No-Face, and the many faceless spirits simply sit on the train, waiting for the sixth stop. Nobody ever speaks to one another for the entirety of the train ride, and each of the spirits leave for the next stop until only Chihiro, No-Face, and the little mouse and bird are all that remain.

Listen to Joe Hisaiashi’s track in this scene, which is so achingly depressing it’s practically the perfect track for a long train ride. Consider the images we see throughout the train ride: a single house and a tree isolated in the middle of the ocean; the way the train coldly passes by two wandering spirits who are clearly father and daughter; the distance between each isolated train stop, the amount of time that passes to get to each one as day transitions to dusk and then night; the way a young girl spirit–clearly around the same age and height as Chihiro–stares blankly away at the train as it passes her by; the neon signs the train whisks by but are not attached to any visible buildings; the look of calm determination on Chihiro’s face as she nears ever closer to her destination; the mouse and bird sleeping on her lap as if her own children; and the reflection on the window contrasting the Chihiro of before and the one of now.

If My Neighbor Totoro is Miyazaki’s celebration of childhood, then Spirited Away‘s single train scene is a requiem: the ultimate depiction of a sad, lonely adult life devoid of joy and laughter. It is the death of youthful innocence; the sunset signaling the start of a long, dark night. Had it not been for Grave of the Fireflies, this single scene would have been the most grim and beautifully depressing thing to ever come out of the Studio–and it’s certainly the most grim and depressing to ever come out of Miyazaki.

But this leads us to the second scene, which acts as the second piece to the broken-heart necklace that begins with the train scene. Whereas the train scene is adult existential despair personified, the “Reprise” scene is the resurrection of joy, as Haku–a mysterious boy who seems to be one of the only people in this world willing to help her–reunites with Chihiro (in the form of a dragon, no less) and she rides with him back to the bathhouse. As she is riding atop him (and considering the wording of that sentence plus the phallic shape of the dragon, it’s safe to assume that sexual awakening is being symbolized here as well) Chihiro manages to sift back through her memories and remember Haku’s true name that Yubaba took from him–the name of a river that she once fell in as a young child that Haku himself saved her from, thus revealing Haku to be an old river god.

And as soon as she utters his true name, a virtuoso moment occurs when she and Haku plummet from the sky, holding on to each other. Not a single ounce of fear is conveyed in their faces, the two of them simply overjoyed that they can remember their innocent identities as they are falling closer and closer to the ground, their tears drifting above them. Whereas the train scene was a lamentation, the falling scene is one of rebirth, suggesting that though childhood is impermanent (they’re gonna hit the ground eventually) it’s never too late to fly and fall down again. Like the train scene, it is sadly not available on YouTube, but really, Joe Hisaiashi’s magnificent music during this scene speaks for itself.

This leads to the film’s conclusion, in which Chihiro is granted her and her parents’ freedom, but only if she could solve a riddle for Yubaba, bringing to mind Greek and Roman myths with similar riddles incorporating high stakes. Yubaba presents a group of pigs to Chihiro, and she’s forced to guess–or perhaps just know–which of them are her parents. She answers that none of them are, and she’s set free. All the other times I saw this film, I questioned how it was she was able to figure the riddle out. I somewhat accepted my own answers and excuses–that she simply knew her parents so well, or that she had grown so much that she could just tell–none of which were all that satisfying, but did the job for me.

It wasn’t until this rewatch, however, that I finally understood after all these years: even if Chihiro’s parents were among the pigs Yubaba had presented to her, she still would’ve been right. Because now that they are livestock, they are not her parents anymore. Just as Haku and Sen had forgotten their true names, they weren’t the river god or Chihiro anymore. Just as Lin and Kamaji and all the other spirits have given up their names, they may never be their true selves. Just as how the office worker drone you may be as an adult is not the same person as the wide-eyed child you grew up as. The person you were before is what defines your identity. And when that’s gone, whether it be through magic or loss of innocence or the pressures of adult society, you are no longer that person.

Such is the harsh reality of adulthood that Chihiro ultimately learns: it becomes harder and harder to hold onto that person when concepts like greed, enterprise, and wrath lurk in every corner. But that doesn’t mean you necessarily have to let go.

The film ends with Chihiro going out the same way she came–complete with the recycling of dialogue and animation from the opening scene–given only one rule: that she must not look back at the bathhouse as she’s leaving, or she’ll lose her newly won freedom, bringing to mind both the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, and the Biblical story of Lot’s wife looking back at Sodom and Gomorrah. This presents to us an interesting paradox: the entire point of the film is to always remember the person you once were before, but at the same time, the only way to be free of the past and come of age is to always look forward. Perhaps, then, the real lesson of Spirited Away is not that you must both abandon and stay true to your past self, but that the person you always were never leaves you. It is–excuse my cheesiness here–inside you all along. So long as you remember your true name, you can still move through the adult world, and keep that flame of innocence in your heart.

Spirited Away is far and away the most successful film to be released by Studio Ghibli. More than just a hit at the box office, it was a phenomenon. It became the first film to ever gross $200 million before even releasing in North America, surpassed Titanic as the highest grossing film of all time in the Japanese box office, and became the first ever Japanese animated film to win an Academy Award for Best Animated Feature (and the only Best Animated Oscar winner to be made outside of America).

With their biggest success in tow, Miyazaki had a mighty hard act to follow with his next film, but before that, a new animator approaches to direct the Studio’s first ever sequel…if it even counts as a sequel. Next time on the Retrospective, we cover Hiroyuki Morita’s The Cat Returns, the follow-up to Yoshifumi Kondô’s Whisper of the Heart.

Previous Editions:

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Previous Movie Mezzanine Filmmaker Retrospectives:

The Darren Aronofsky Retrospective

The Terrence Malick Retrospective

3 thoughts on “The Studio Ghibli Retrospective: ‘Spirited Away’”

I always knew Spirited Away was about the brothel work place, but I never really thought about it being /our/ workplace, and that we forget our identity as our lives progress. That’s interesting.

Your analysis of the ending with Chihiro’s parents also makes a lot more sense than anything I’ve thought of.

Thanks for your thoughts, I will be reading the rest of your Ghibli retrospectives!

I really enjoyed reading this piece, Christopher! I came across “Sen to Chihiro no kamikakushi” two years before it’s released in the US as Spirited Away. It was my first time seeing a Ghibli Studio movie, and I was immediately enchanted with the movie within 2 minutes. Seeing a vividly imaginative story telling at its best was really memorable. Now thanks to you, I want to see it again!

Pingback: Review: Spirited Away (8/10) | scottmathis