When I first saw No Country for Old Men in theaters, I thought it was an immaculately crafted film but I couldn’t get past the queasy feeling that the Coen Brothers’ adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s 2005 novel was an immoral one. After all, the hero dies while evil triumphs and gets to walk away from it all. I saw it again and this feeling sunk even deeper. But, upon my third recent viewing, I realized that No Country for Old Men is far more morally complicated than it appears at first glance.

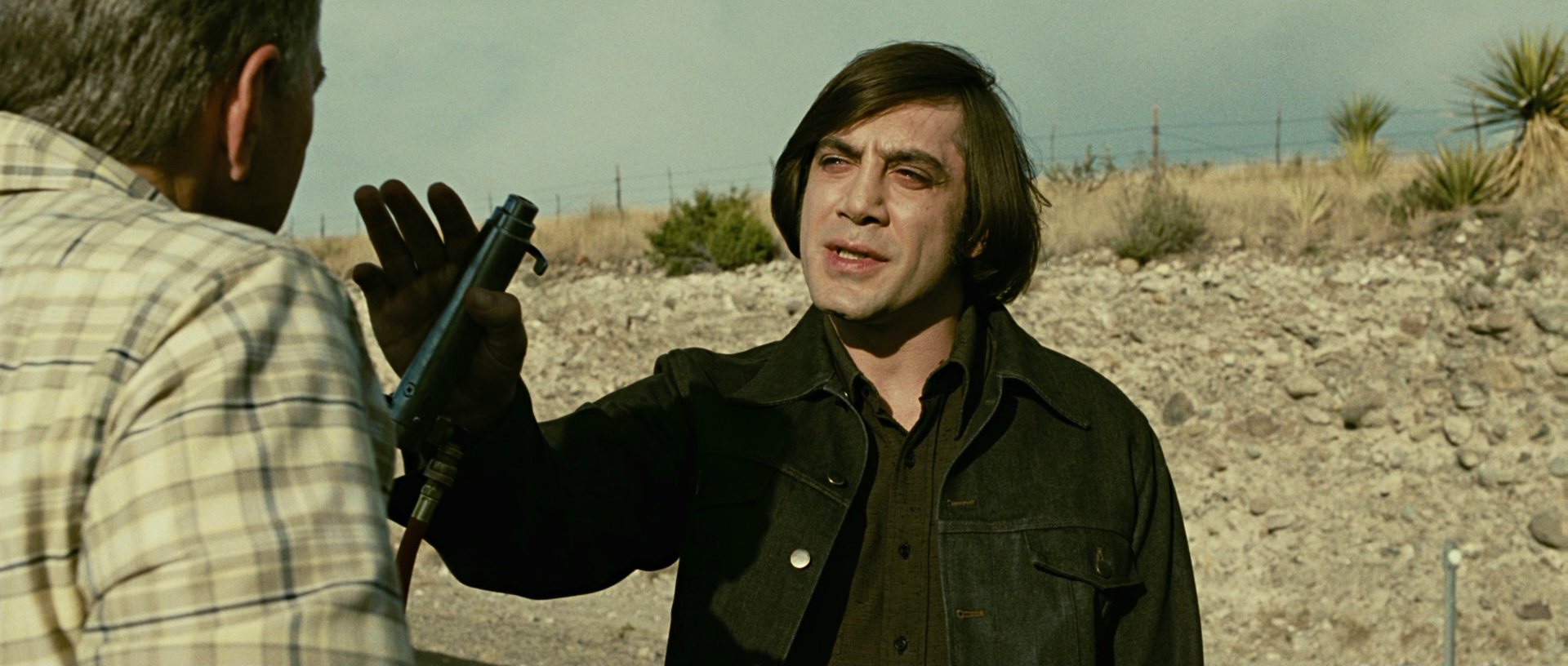

The main moral force of the film is Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), a psychopathic killer who often leaves a coin toss to decide who lives or dies. He represents random, indifferent suffering. The coin is his morality. Only random chance makes sense in such a world. Likewise, many of his killings are pointless and done in such a cold, clinical manner that it’s not certain if Anton gets any pleasure from the killing.

By the end of the film, he’s killed the ostensible hero of the story, Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin) and possibly killed his wife, Carla Jean (Kelly Macdonald) as well. Sure, he doesn’t get the money he’s been hired to recover, but he walks away with his life and, more importantly, fulfills both his personal promise to kill Llewelyn for inconveniencing him and also his threat to visit Llewelyn’s wife.

Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), a small-town sheriff, follows Anton’s path of destruction and is unable to comprehend the evil he sees. He talks about the senseless and brutal killings he reads in the paper with a sort of sad indignation. How can people be so evil? Why do they get free rein over the earth and triumph over good people?

All this led me to believe on my first viewing that No Country for Old Men is a nihilistic picture, a post-modern Western that examines the disillusionment towards good triumphing over evil and the hero riding off into the sunset. Seeing it again, though, while nihilism is certainly still there, overall, I was surprised to find a considerable measure of hope in it.

For one, there’s a deep sense of morality in the film. It’s easy to see Llewelyn as the hero of the piece, but he makes a choice early on to take the money that leads to the entire chase. Maybe death is a steep penalty for theft, but perhaps not. Llewelyn does something evil and Anton is a sort of grim reaper coming to punish him for his transgressions.

But more than that, the characters refuse to buy into Anton’s philosophy. When Anton tries to cut a deal with Llewelyn, Llewelyn refuses, believing that he can save himself, his wife, and keep the money. He’s wrong, it turns out.

The whole linchpin of this rejection of Anton’s nihilism comes when he confronts Carla Jean at the end of the film. He says he will leave her fate to the coin and asks her to call it. She refuses, saying it is Anton who makes the choice to kill, not some random flip of the coin, and thus demanding that he take responsibility for his brutal actions. Even as random as the violence may seem, Carla Jean refuses to accept the world as simply an indifferent flip of a quarter.

Right after this scene, Anton’s philosophy comes back to bite him in the ass as he gets T-boned by another car, breaking his arm and leaving him bloody in the street. Random chance has made him the victim this time around. His belief in a world of chaotic evil is disrupted by two boys who come to his aid as he lies on the street. Anton offers to buy the shirt from one of the boys, but the boy offers his shirt for free and only reluctantly takes the money. Anton is thus undone by the simple goodness of ordinary, everyday people. The world is not nearly as senseless or evil as he would like to believe it to be.

But where does that leave Ed, this old man unable to comprehend all that he’s seen? As he talks to others, he doesn’t save Llewelyn or arrest Anton, and he certainly doesn’t solve the problem of evil. He’s left just as flabbergasted as he was at the beginning of the film.

The Coen Brothers tell a similar story in Fargo. Marge Gunderson (Frances McDormand) is a chipper small-town police chief who is seven months pregnant. Like Ed, Marge becomes embroiled in a world of evil as she tracks down two hired kidnappers—Carl Showalter (Steve Buscemi) and Gaear Grimsrud (Peter Stormare)—by following the victims of Gaear’s bloodlust. Unlike Ed, she finds Gaear, but not before he has shoved most of Carl’s body through a wood chipper after a petty disagreement about who keeps the dealership car their corrupt benefactor gave them.

Marge places Gaear in the back of her car after wounding him as he tries to escape. On the drive back to the police station, Marge lectures Gaear about the people he’s murdered for money: “There’s more to life than money, you know. Don’t you know that? And here ya are, and it’s a beautiful day. Well, I just don’t understand it.” Marge, like Ed, isn’t able to comprehend the evil she sees, but justice wins in the end and Gaear faces the condemnation of the law. The film ends with the promise of new life in Marge’s unborn child. Marge’s simple goodness is a flame in the midst of a cold, dark world.

Similarly, at the end of No Country for Old Men, Ed tells his wife about a dream he’s just had: a dream of his father riding on a horse with a horn carrying a flame. His father says not a word as he passes but Ed knows that his father has ridden on ahead, braved the dark and cold, to prepare a fire for Ed. If that’s not the most eternally hopeful ending a film could have, I don’t know what is.

Anton only wins in the most superficial sense. He may escape the grasp of man’s law, but Ed’s dream imagines something greater beyond this mortal coil. After all, Anton may kill others, but what has he gained? He is none the wealthier or wiser by the end and none of the good people have come around to his way of thinking. But some men, men like Ed, have a hope far greater than anything Anton could begin to imagine. There may be no country for old men, but perhaps there is a kingdom for them.

3 thoughts on “The Complex Morality of “No Country for Old Men””

Just to correct you, he doesn’t kill Moss, and he does recover the money.

Yes. Hard to take this interpretation seriously when the author doesn’t know what actually happened in the film.

Yeah. Anton does get the money, and he does kill the wife. Hence why he checked his shoes. Attention to detail Mr Author! I stopped reading after it said he didn’t get the money. Attention to details says he got the money. There was scratch marks on the duct in the motel when Bell was in there, and he gave those kids a $100 bill.