It’s not easy to shock Mel Brooks, and even harder to offend him. But there is one place where he draws the line. In Ferne Pearlstein’s upcoming documentary The Last Laugh, which explores the impact of World War II and the Holocaust on Jewish comedy, Brooks is asked point blank if he could ever make jokes about said Holocaust. His response: “No. I can’t go there. I personally, who have done a musical called The Inquisition, with Jews floating around and being dunked in water and tortured—I cannot go there.” Nor could he bear seeing other comedians make such jokes. During the presentation of his Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2013 AFI Awards ceremony, when Sarah Silverman cracked a joke about how the thing the Jews hated most about the Holocaust was the cost, Brooks looked visibly shaken and disturbed.

For Brooks, one of the defining voices of 20th-century comedy, Jewish or otherwise, it’s one thing to mock Hitler and the Nazis. He built his career on it, from doing Hitler impressions in stand-up sets in the Catskill Mountains in the late 1940s to his breakthrough directorial debut, The Producers (1967). “Anything I could do to deflate Germany, anything, I did,” Brooks recounts. It was revenge through ridicule. But how are you supposed to ridicule an act of genocide? There is no revenge to be had laughing at millions of innocent men, women, and children being slaughtered. It brings no comfort to the survivors, no justice to the victims, no punishment to the perpetrators.

Not that that hasn’t stopped artists from trying to grapple with the Holocaust through humor. The results have, to put it delicately, varied. On the one hand, you have Jerry Lewis’ unreleased, and apparently tone-deaf, The Day the Clown Cried, a film about a clown forced by the Nazis to entertain children about to be executed in the gas chamber. On the other, you have Roberto Benigni’s Life is Beautiful (1997), an Academy Award-winning tragicomedy about a father who protects his son from the horrors of the Holocaust after they are interned in a concentration camp by tricking him into thinking that it’s all a highly orchestrated game. (For the record, when asked about it in The Last Laugh, Mel Brooks calls it one of the worst films ever made, while Abraham Foxman of the Anti-Defamation League calls it one of the best.)

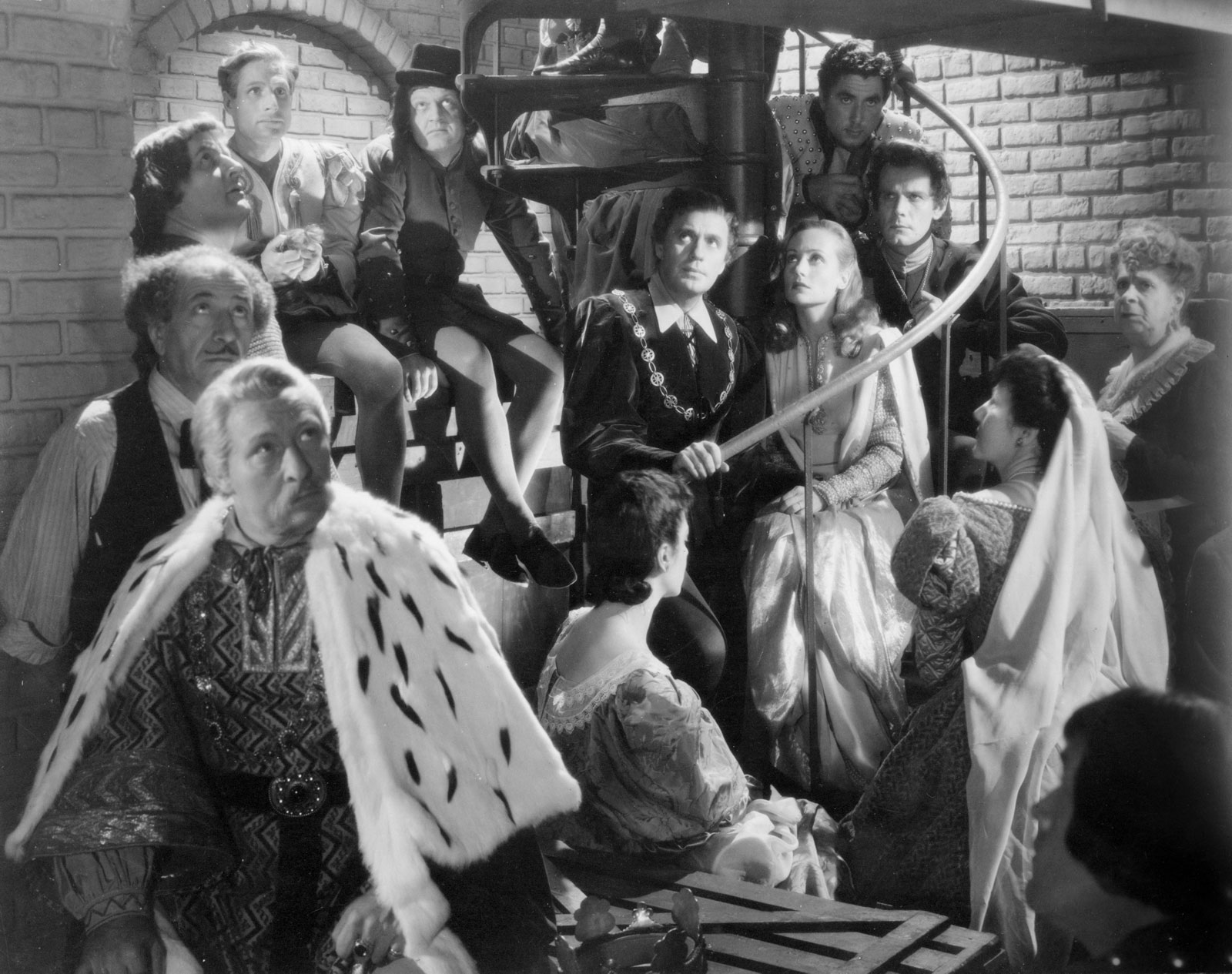

But somewhere in the middle of the spectrum of good and bad taste is Ernst Lubitsch’s To Be or Not to Be (1942), a wartime Hollywood comedy about a troupe of actors in Nazi-occupied Poland who help stop a Gestapo plot to eliminate the Polish Underground. The troupe is led by infamous ham actor Josef Tura, played by the very popular—and very Jewish—Jack Benny. His wife and co-headliner Maria—played by the equally popular yet conspicuously not-Jewish Carole Lombard—enters into an affectionate yet chaste affair with Polish Air Force pilot Lt. Stanislav Sobinski (Robert Stack). When the Nazis invade Poland, Sobinski and the other surviving pilots relocate to Great Britain. Upon learning that Polish resistance leader Professor Siletsky (Stanley Ridges) is returning to Europe for a clandestine mission, they give him the names and addresses of their families and their contacts with the Underground so he can give them messages. But when Siletsky doesn’t recognize Maria Tura’s name when asked to contact her, Sobinski realizes that he can’t be a real Pole—it would be like an American not recognizing Rita Hayworth or Betty Grable. When the Allied Command realizes that Siletsky is a double agent, they order Sobinski to return to Poland, rendezvous with the Underground, and eliminate him before he gives the info to the Gestapo.

The ensuing scramble elevates To Be or Not to Be to the heights of Hollywood comedy, with Josef’s troupe impersonating various Nazi officials in order to deceive Siletsky into giving them his contacts. Lubitsch deftly mixes espionage intrigue with screwball romantic shenanigans as Siletsky falls for Maria, Sobinski falls even further for Maria, and Josef damn near ruins the whole operation with jealousy and fury over his wife’s affair. As petty romantic squabbles upend the troupe’s deceptions, Josef, Maria, and Sobinski are forced to assume more and more false identities until barely anybody can keep straight who’s who anymore. The film climaxes with the troupe crashing a Nazi event attended by Adolf Hitler at their theater where one of their number, a bit player named Bronski (Tom Dugan), impersonates the Führer and rescues Maria from the predations of the bumbling yet vicious Gestapo commander Colonel Ehrhardt (Sig Ruman). Having saved the Polish Underground, Josef, Maria, Sobinski, and their entire troupe escapes to England.

Though coolly received by audiences of the time, To Be or Not to Be has since been heralded as one of Lubitsch’s best films and one of the greatest comedies of its era. Key to this re-evaluation was the film’s brazen lampooning of Nazism in a time when the war was far from decided. Allied victory was hardly assured in February 1942, the film’s original release date: Japan’s supremacy in the Pacific wouldn’t be toppled until the Battle of Midway later in June, and the Allied invasion of Italy wouldn’t be for another year. Axis victory was still a very real, very scary possibility. And yet here was a film—a comedy, no less—where Jack Benny dresses as a Nazi, Carole Lombard flirts with several members of the Gestapo, and one of the troupe’s actors—the Jewish-coded Greenberg (Felix Bressart)—creates a distraction during a Nazi event by reciting Shylock’s “Hath not a Jew eyes?” speech from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. It was bravery the likes of which many audiences weren’t prepared for.

An outcry was understandable when Mel Brooks announced that he was going to remake it in 1983. But that failed to stop one of American cinema’s greatest provocateurs. The remake condensed, clarified, and expanded Lubitsch’s narrative. For one, the characters of Josef Tura and Bronski were combined into one character, Frederick Bronski (Brooks). And a confusing subplot in the original film concerning whether or not Maria—here named Anna Bronski and played by Brooks’ real-life wife, Anne Bancroft—was a member of the Polish Underground was omitted entirely. But for the most part, the original film’s story beats were left intact.

But though directed by Brooks’ long-time choreographer Alan Johnson, To Be or Not to Be is a Brooks film through and through. Freed from the ravages of the Hays Code, the remake traded Lubitsch’s effete, Continental manners for Borscht Belt bawdiness. The jokes are bigger, naughtier, and more absurd. There are three separate musical numbers where Brooks & co. are allowed to stretch their song-and-dance muscles, the best being one entitled Naughty Nazis where Bronski dresses as Hitler and bemoans to his Gestapo lackeys that he doesn’t want war, just “Peace! Peace!…A little piece of Poland, a little piece of France! A little piece of Portugal, and Austria, perchance!”

Most tellingly, Brooks brings the Jewish element of Lubitsch’s film to the forefront. The plight of Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland was present in the original, but it was largely ignored in favor of telling a story about Polish/European resistance. Everything from the opening montage of Warsaw shop windows bearing Polish family names to the non-kosher meals of salami and cheese sandwiches eaten by the characters underscores the otherness of Polish Jews. Of all the characters, only Greenberg was explicitly Jewish, and even then, the word “Jew” is never used.

But Judaism is integral to Brooks’ film, even though neither Brooks’ nor Bancroft’s characters are Jewish. Far from being othered, the Jews are considered an important part of thespian culture. As Bronski mutters after a Gestapo interrogation, “Let’s face it…without Jews, fags, and Gypsies, there is no theater.” In one of the added subplots, the Bronskis hide a group of Jewish refugees during a Nazi round-up in their theater. When it becomes clear that the Bronskis need to flee Europe after helping to kill Siletsky, Anna convinces Frederick to bring them along in one of the film’s most powerful exchanges:

“How can we take them?”

“How can we leave them?”

The film then considerably rewrites Lubitsch’s climactic scene at the Nazi rally by including the Jewish refugees in Bronski’s troupe’s scheme to escape. During one of the troupe’s established acts, a farce involving clowns, they dress the Jews up like the actors and have them exit the cellar where they were hidden, enter onto the stage, proceed down through the central aisle as part of the act, and board a disguised Nazi truck on the street to be taken to an airfield. Perhaps the best moment in the film comes when one of the Jews, an elderly lady, can’t go through with it and starts to crack up while halfway down the aisle. The audience full of Nazi officers look on suspiciously until one of the troupe members grabs one of their hats, throws a Star of David onto the woman, and yells “Juden! Juden!” He pulls out a prop gun that shoots a Nazi flag, yells “macht schnell,” and escorts her out of the theater as the officers roar with laughter. No other scene better underscores Brooks and Johnson’s ability to juggle comedy and pathos—the situation may be comedic, but there’s not a drop of humor in any of it.

The whole film is effused with a dignified, even occasionally mournful, gravitas reminiscent of Lubitsch’s original. The invasion of Poland is treated as a tragedy: Johnson shoots the scene of Nazi stormtroopers marching into Warsaw with Frederick and Anna looking on in devastation in black-and-white. The cheerful song sung by the exiled Polish pilots in Britain before they unwittingly hand off their secrets to Siletsky is changed from a rowdy, rousing sing-along in the 1942 version to a slow choral lament. And the scene where Greenberg performs his Shylock speech is treated as one of the film’s emotional climaxes instead of just one part of a multi-step scheme.

Brooks even deconstructs one of his favorite go-to gags, the flaming homosexual. The film updates Maria Tura’s dresser, a minor, insignificant character in the original film, into Sasha (James Haake), one of the most ostentatiously gay characters this side of Bronson Pinchot in Beverly Hills Cop (1984). At first, he seems like another gay stereotype like Roger De Bris from The Producers, speaking with an obnoxious lisp, dressing in women’s clothing, and gleefully gossiping with Anna without having an affair with Sobinski. But as the film goes on, his subplot darkens considerably. The scene where he reveals to Anna that he has to wear a pink triangle is heartbreaking. “I hate it…it clashes with everything,” Sasha bravely jokes to Anna. Neither of them thinks it’s funny. After being arrested by the Gestapo, Frederick and Anna make his rescue one of their main missions, tricking Colonel Erhardt (Charles Durning) into releasing him. The humanization of Sasha is completed during the aforementioned theater-escape scene: He is the one who puts the Star of David on the terrified woman and escorts her out of the theater. Much like the dignified treatment of Jews in the original film, Brooks’ treatment of Sasha is especially prescient from today’s perspective considering that at the time, the LGBTQ+ community was in the throes of the AIDS epidemic. It’s perhaps too much to say that the film is pro-LGBTQ+, but it is one of the few films of its era to make an obvious homosexual both a human being and a hero.

Comparisons between To Be or Not to Be and The Producers are inevitable, with Brooks mercilessly lampooning the Nazis in both films. But the former takes place in a real world full of tragedy, while the latter is fantasized burlesque. The Springtime for Hitler number in The Producers is shocking and absurd, but it takes place in a universe that is in itself shocking and absurd, full of unscrupulous agents who sleep with dozens of old ladies, grown men neurotically attached to blue blankets, and drug-addled flower-power weirdos. Furthermore, it only works so well as comedy because it takes place in an era and culture where condemnation and condescension towards the Nazis was taken for granted as the norm. But late 1930s Poland had no such benefit. That’s what makes To Be or Not to Be so much braver and more necessary in these precarious times: It finds ways to defang the horrific and unthinkable without punching down. It admits that human monsters are real and powerful, but they need not be invincible.