Pom Poko is a strange film, and not just for the obvious reasons. Isao Takahata’s first foray outside of the realism that defined his previous two features in the studio contains a premise that’s strange enough on its own; about a clan of Japanese raccoon dogs–known in their homeland as “tanuki”–whose home is being ravaged by the growing presence of urban development and how they set out to fight back against the humans and reclaim their territory. When you think about it, a good bit of American animated films have ripped this premise off, most notably Dreamworks’ thankfully forgotten Over the Hedge. So what makes Pom Poko even stranger? There are many factors, but you can’t hear them over the sound of one word: Balls. So. Many. Balls.

Pom Poko is by no means a particularly good film. In fact, it might even be the studio’s weakest effort in the realms of storytelling. But as a cultural curiosity and a showcase for stunningly bizarre animation, there’s nothing else quite like it.

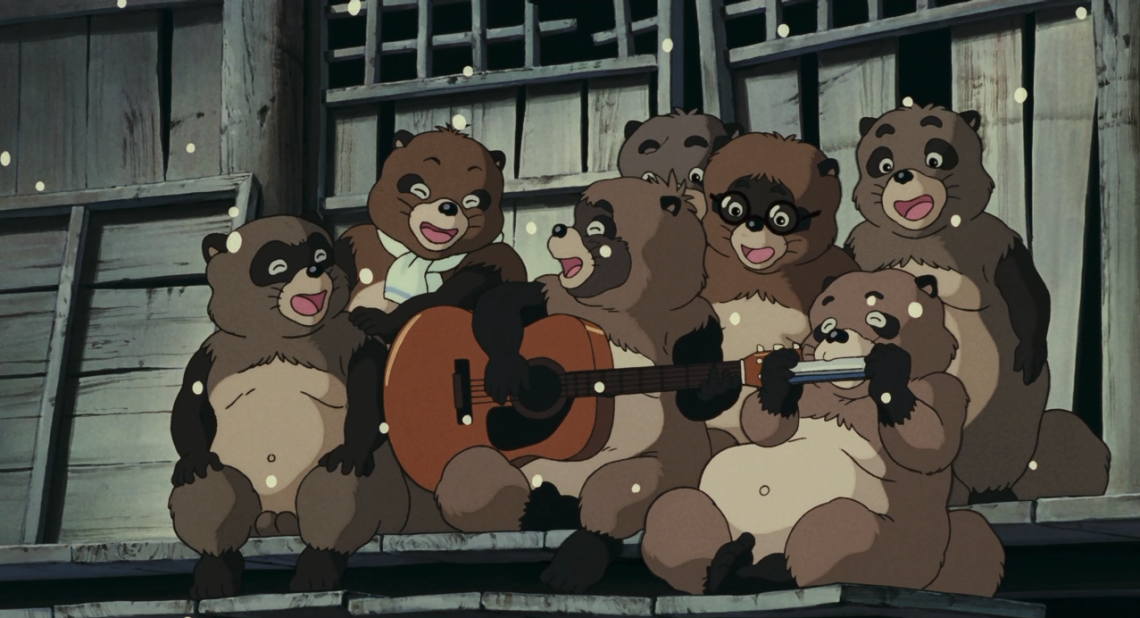

The detail I forgot to mention, the one that ultimately sets Pom Poko apart from the films that it inspired, is that the tanuki in question inexplicably have the ability to transform into any object or form they so desire–a popular aspect of the creature in ancient Japanese folklore–and they use that gift to infiltrate human society by disguising as ordinary objects or even humans. This is where the aforementioned bizarreness comes in, as the tanuki employ several different tactics to drive the humans away from their homeland.

At first, no joke, they use their skills to flat-out murder a bunch of people (y’know, for kids!) by transforming into bridges that disappear and send construction workers plummeting to their deaths, or pretending to be civilians on the road that cause their cars to swerve off the road. When that doesn’t work, they resort to scaring humans by using their transforming abilities to pretend to be vengeful spirits haunting the forest, leading to a plethora of odd scenarios and eye-popping visuals that give the film a surreal, manic energy. Unfortunately, that same energy wears out its welcome even before we’ve gone halfway through the film’s two hour running time.

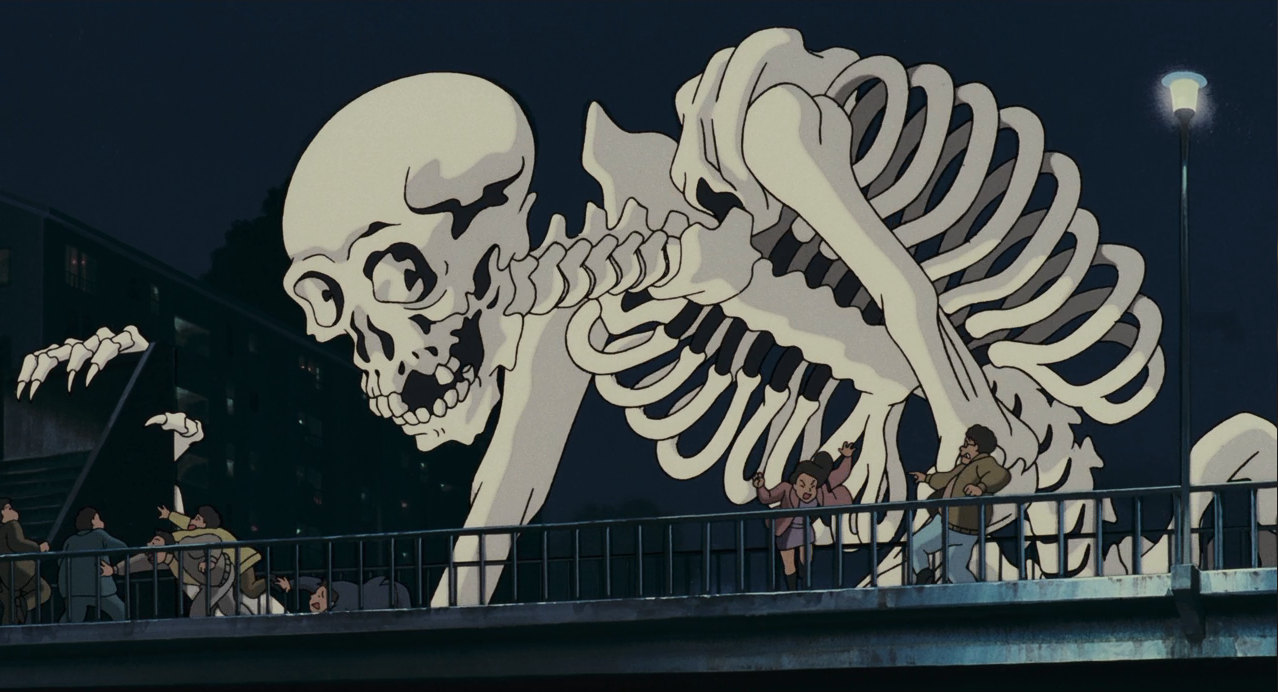

The film’s oddness peaks in two specific scenes in the second half. The first is when the clan devises a large scheme that requires channeling all of their faculties into creating a series of transformations and illusions large enough to terrorize the entire town. Soon, the humans bear witness to gigantic, bizarre monsters crawling across the buildings to create a spectacle that even Salvador Dali would have been terrified of. There’s even a large tsunami that materializes out of nowhere, sweeps up a few people, and then vanishes without a trace. The scene goes on much longer than it needs to just so Takahata and his animators can relish and indulge in making trippy visuals.

The second scene, which is the one that every viewer of the film has embedded in their brain, is an infamous sequence near the end in which a band of tanuki, realizing it’s all or nothing, attack a band of policemen with their giant testicles. In Japan, tanuki are actually known for having large testicles, and there are a lot of famous artistic depictions and Japanese folk songs that make reference of that. But with the tanuki’s shapeshifting powers, their balls become twenty times larger so they can turn into trampolines, parachutes, and even weapons. Seriously, just look at this scene and be awed.

As you can already tell, there’s an inconsistency in this film between juvenile and raunchy humor that, weirdly enough, is considered somewhat acceptable in Japan (like many of Studio Ghibli’s films, it was the highest grossing movie at the Japanese box-office the year of its release, and was a hit with families) but would never fly well in the West. In a way, it’s kind of fascinating to watch as an outsider what kind of humor the Japanese make of their folklore. If nothing else, this is the kind of movie that can be used for anthropological studying; a film of such cultural specificity that it barely translates.

And despite Pom Poko‘s schizophrenic mixing of childish and mature elements, there’s something self-aware about the way Takahata incorporates larger stakes and adult humor to the proceedings. The most notable example of which is when the tanuki are unable to resist their animal urges and end up mating during the spring time. The scene is played for laughs at first, and then romance when two main characters end up having children together. Later, though, that humor is undercut when we learn that the clan’s population has spiked at precisely the time that food and shelter have begun to grow scarce. For all the lunacy that powers this film, there are real stakes and consequences to the characters’ actions that Takahata fully acknowledges and incorporates all throughout the film.

While the tanuki are constantly arguing about how much they hate the humans for taking their land away from them, the only way they’re able to even fend them off is through human tactics. They find an old television that they use to gather intel and news about what’s going on in the human world, becoming absorbed in the media firestorm that their “terrorist” actions create. When having to find another means of food distribution, one of the tanuki suggests a human society-like organizing method that forces one of the militant members of the clan to question his allegiance. It’s almost like some sort of cruel, cosmic joke. Even when they’re fighting human culture, they’re only sucked into it further.

This irony forms into a rather potent, tragic punchline in the film’s conclusion, which is in no way a happy ending. The clan loses, urban development continues on, and many of the tanuki die. The remaining ones are forced to disguise themselves and live among the humans. One of them even has a desk job and uses public transit while his wife works at a bar. Even an animal of nature is forced into the crushing modernity of urban life, which is as somber a finale as you can get from this kind of movie.

The final sequence tries to incorporate a helping of hopefulness to soften the dour denouement (resulting in a rather poorly thought-out moment in which one of the tanuki breaks the fourth wall to give a lesson to the audience), but that irony is still there. It’s unfortunate that while the rest of Studio Ghibli’s family friendly offerings could be enjoyed by all ages, Pom Poko leans a bit too heavily on the juvenile side, even though there are some interestingly mature developments that keep it from being outright childish film. If nothing else, it’s worth watching for its astounding animation and as an artifact of what a different culture perceives as family entertainment.

Meanwhile, Hayao Miyazaki was still working on his next project, which would be the biggest and most ambitious one he’d attempted since Castle in the Sky at the time. In the meantime, however, Studio Ghibli was ready to debut their first film from a director that wasn’t from the co-founding duo of Miyazaki and Takahata. On the next installment of the Studio Ghibli Retrospective, the criminally underseen and underappreciated masterwork from Yoshifumi Kondo, Whisper of the Heart.

Previous Editions:

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Previous Movie Mezzanine Filmmaker Retrospectives:

The Darren Aronofsky Retrospective

One thought on “The Studio Ghibli Retrospective: ‘Pom Poko’”

The last bit about how the film is interesting as an example of what one culture considers family entertainment smacks of jingoism. Considering the pernicious ideological baggage that Western family media tends to haul around, while raccoon dog ‘pouches’ having magical qualities is certainly absurd and strange, it is in a lighthearted way. Along with the film’s other themes, it is still a better overall quality of film to put a kid in front of than some sort of disney or pixar consumerist schlock.