Studio Ghibli was officially formed in 1985 after proving themselves with Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind a year earlier. Believe it or not, the name “Ghibli” actually comes not from the Japanese language, but from a mispronounced Arabic word referring to a warm wind that would be carried all the way from the Mediterranean to the arid Sahara deserts of Africa. It’s a name that highlights the studio’s intention from the get-go: to bring a breath of fresh air to Japanese animation.

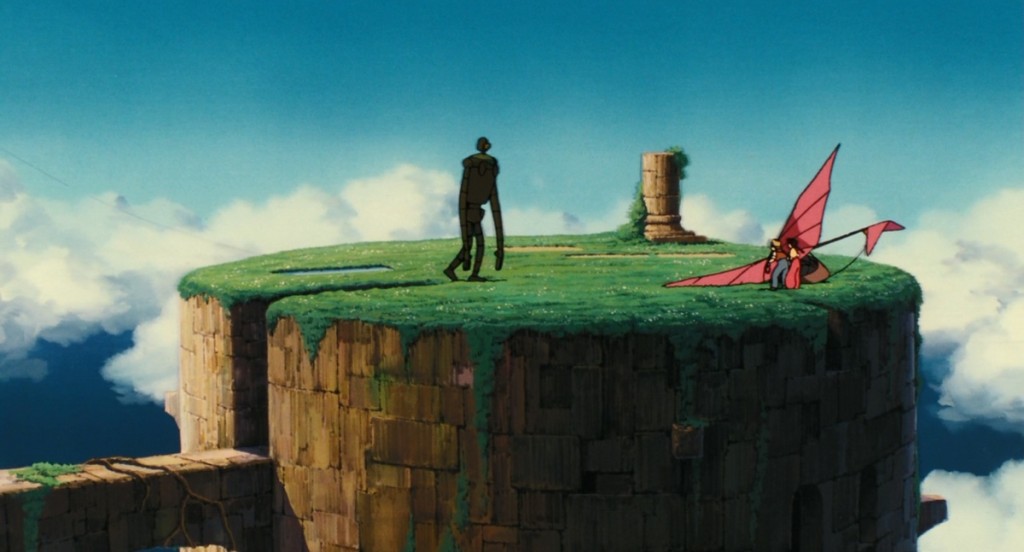

No longer needing to outsource their animation to a separate company, Hayao Miyazaki had more control than ever over his team of animators was even given a higher budget for their first feature as a fully-formed studio. That feature was Castle in the Sky, which revolves around a central image that may very well encapsulate the wonder and optimism that makes Studio Ghibli so beloved: that of a floating fortress hidden in the clouds, an image full of majesty and mystery, wonder and awe, a youthful belief in the impossible and the promising future of progress. Years later, it’s easy to see why it’s become one of Ghibli’s most enduring images, alongside their emblematic Totoro.

“Take root in the ground, live in harmony with the wind, plant your seeds in the winter, and rejoice with the birds in the coming of spring.”

Castle in the Sky is a children’s adventure story filled with lovable characters, imaginative visuals, a simple yet essential moral, and breathtaking action and animation. If any film in the studio’s filmography has inspired the works of Pixar, it’s surely this one.

The film takes place in a fantasy/steampunk setting—like Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, only without the post-apocalypse angle—that melds magic and spellcraft with giant robots and imposing airships. It opens as a young girl named Sheeta is almost kidnapped by air-pirates, only to fall from the sky as a result. She lands in the arms of Pazu, a boy her age who lives in a mining village and is obsessed with building an airship of his own so he can find the mythical kingdom of Laputa, which resides on a floating island in the clouds that may contain untold treasures. When it’s revealed that Sheeta may actually be the last living citizen of Laputa and the key to unlocking its treasure, this sets off a chain of events as pirates, military forces, and a deliciously evil government agent all begin a frantic chase for the girl and the castle in the sky.

The plot feels heavily inspired by old serial adventures, but it’s remarkable how Castle in the Sky brings together disparate elements to create something both universal and incomparably original. Why force yourself to work in either fantasy or science fiction when you can have both? And if you’re going to have a story inspired by American serial novels, why not make the visual design an inventive mixture of European and Asian influences? And why not take things off the ground, while we’re at it? The movie continually amazes with its fresh, inventive world, and this constant marrying of different visual and conceptual influences would continue to evolve throughout Miyazaki & Studio Ghibli’s career.

The finely tuned visuals are paired with composer Joe Hisaiashi’s best work to date. The main opening credits theme is honestly one of the best film score themes I’ve ever heard. It’s immediately recognizable, epic, wondrous, innocent, and elegantly composed, not only setting the mood but also capturing the feeling of discovering its titular monument. Hisaiashi opens with a string of piano notes as wistful as the passing of the clouds, a playful yet brief segment of brass and woodwind instruments evoking childlike innocence, and finally an increasingly powerful, rising sense of awe as the flying kingdom emerges from those very clouds.

The rest of the score propels and complements the action beautifully as well, though there are actually two different versions of that score depending on which version you watch. The original Japanese iteration had a more synth-inspired score, while the American release is more orchestral and bombastic. Hisaiashi was actually happy to expand on his score for the American version, creating some additions to his music that arguably improve the overall picture. Regardless of which version you listen to, it’s phenomenal work by a musical artist at the height of his powers.

Of course, Castle in the Sky wouldn’t have worked if it was just pretty pictures and sounds without fun characters to guide us along. Pazu and Sheeta are childhood innocence and wonder personified, and they’re both incredibly charming without being cloying, even if they don’t have quite the surplus of personality found in, say, Porco Rosso or Chihiro from Spirited Away. It’s the supporting characters that are the most fun to watch, however, like the aforementioned villain chewing every inch of the hand-drawn scenery (voiced in the English dub by none other than Mark Hamill), as well as the delightfully goofy band of air-pirates who are all captained by their domineering mother.

All of these qualities fuse together to make superlative action sequences, which I’d argue compare with the pure, adventurous spirit of the Indiana Jones pictures. Not only is each one lovingly animated, but they manage to communicate more than just excitement. Some of them are really funny, as the bumbling air pirates banter back and forth, while others communicate more pathos than even the film’s more heavily dramatic scenes, such as one in which Sheeta witnesses the death of the robot that protects her. They all manage to advance the plot, world, or characters; there’s hardly a wasted scene in the entire film, and the exceptional pacing spurs everything further.

The film’s marriage of different aesthetics and influences actually manages to fit quite nicely with its overarching themes. It’s no accident that two completely different things are always sharing the same space, from a witch that’s protected by a giant robot to a band of pirates being commanded by an old lady. This is because just about all of Studio Ghibli’s films—namely Miyazaki’s work—are about the balance between two seemingly irreconcilable forces. In Nausicaä, it was as simple as nature and humanity having to share the same earth. In Castle in the Sky, there’s actually more than one dichotomy at work.

At first, Laputa appears to be nothing more than a myth, a lost kingdom similar to Atlantis. As the layers are slowly peeled back, however, we learn that it’s actually a technological marvel of constantly rotating propellers, guarded by giant robots that can both tend the gardens and destroy anything on sight with equal effort. Further scenes reveal that the castle is also powered by a large, magical crystal, confirming that both technology and magic are responsible for this sovereign wonder. Nature also plays an important role. Laputa is also lush with gardens, man-made rivers, and a giant tree growing from the center, its roots supporting the very base of the island.

These forces are in a state of balance, and the villain attempts to tip the scales by exploiting its technology for his own cruel ends. Laputa is ostensibly a monument of progress, representative of the potential that mankind can unlock when in harmony with the uncontrollable elements. However, that potential can take on new meanings and results depending on who controls it, and this brings up the film’s second main duality: innocence vs. adulthood—or rather, optimism vs. cynicism.

This struggle between the world of children and that of adults is presented as eternal as that between good and evil, as the latter attempts to seize the once innocent castle with corrupt motives. The children, of course, win the day thanks to The Power of Love™, but it’s less a victory for the world and more of one for innocence, optimism, and human empathy. Castle in the Sky calls for the thing that Laputa itself represents: balance. Only when different forces coexist can humanity be its best. At the same time, however, the film realizes that attitudes of innocence and cynicism will always be in conflict. The stance it takes isn’t as IQ-numbingly simplistic as “Adults are evil jerks who don’t know how to feel love anymore,” but that if there’s one quality that’s more important than the other, it’s that which allows for love, forgiveness, and kindness.

Castle in the Sky was a success at the Japanese box-office and also managed to find an audience in North America. It wasn’t nearly as successful as their future endeavors, but that’s understandable since this was a first feature for a premiere animation company. Overall, the film did more than enough to establish Studio Ghibli as a voice to keep an eye on, and as their name predicted, they brought a breath of fresh air to a nearly barren landscape.

Now that they’d proven themselves, what would come next for the still newborn studio? Believe it or not, Ghibli began work immediately after Castle in the Sky on not one but two new features, one from Miyazaki and the other from co-founder Isao Takahata. They could not be anymore different, and next week we’ll examine both. One brings with it a cinematic despair like no other, as we dive into the haunting WWII drama from Takahata, Grave of the Fireflies. But before that, we can’t continue on without taking a look at Studio Ghibli’s flagship title, Miyazaki’s beloved classic My Neighbor Totoro.

Previous Editions:

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Previous Movie Mezzanine Filmmaker Retrospectives:

The Darren Aronofsky Retrospective

6 thoughts on “The Studio Ghibli Retrospective: ‘Castle in the Sky’”

This is no doubt his crowning achievement.

It’s definitely in my Top 5, though I have another film that I consider his greatest that I’ll be talking later in a few weeks.

That being said, I finally got a chance to see The Wind Rises, and that film is really hard to shake off.

The site’s new design compliments these reviews well. It’s great having such vivid clear pictures (more like paintings) of Miyazaki’s work. As usual, great reviews and keep them coming.

Thanks! I love the new design too. Be sure to thank Andrew Robinson, Corey Atad, and our editor Sam for the bang-up job! I agree that it really makes the screenshots sing out. More retrospective pieces along the way!

Sometimes I think Castle in the Sky is Miyazaki’s masterpiece. It takes those core themes and ideas he loves like Nature vs Mankind, the old vs the new, and his love of aviation and puts in a wonderfully-paced, gorgeous action adventure. He doe similar stuff in Nausicaa and Princess, but the lighter, breezer tone here makes his themes more palatable to my taste(especially compared to Mononoke, a movie that demands respect more than admiration in my eyes).

But then I watch Spirited Away again and its like, “No, this one is definitely the best still”.

I just spend an entire weekend watching as many Miyazaki movies as i could,

I LOVE adventure movies, with steampunk’ish tech, strong female characters (they are pretty much impossible to find in the anime industry, trust me, I spend a long time searching)

I’m a bit annoyed I didnt discover these sooner, but non the less, my personal favorites of Ghibli and Miyazaki movies is, in no particular order:

Laputa, Valley of the wind, howls moving castle, Porco Rosso . Princess Mononoke, Spirited away,

I prefer the mechanical ones the most though, and I keep thinking about Laputa, since that’s what i kicked off my marathon with, and I can barely remember it, since it was so breathtaking for an 32 year old anime movie, I had no oxygen left in my brain to remember stuff with =)