In 1985, veteran Japanese animators Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata co-founded the little animation company that could, Studio Ghibli, alongside Toshio Suzuki and Yasuyoshi Tokuma. Like most upstarting anime companies, the team at Ghibli were unaware of how their work would be received by the Japanese public, let alone the rest of the world. However, it quickly became the only Japanese animation studio whose output was adored both internationally and universally, not only by hardcore anime buffs but also cinephiles and mainstream audiences alike.

Company leader Hayao Miyazaki recently announced his retirement from animation. With his final film, The Wind Rises (or Kaze Tachinu), approaching its North American release, the company will soon go through a major turning point. And what better way to celebrate Studio Ghibli than with a Movie Mezzanine Filmmaker Retrospective?

It’s hard to describe the spark that gives Studio Ghibli films their universal appeal. Roger Ebert summed it up best in his Great Movies article regarding their flagship film (and arguably their most famous), My Neighbor Totoro: “Here is a children’s film made for the world we should live in, rather than the one we occupy. A film with no villains. No fight scenes. No evil adults. No fighting between the two kids. No scary monsters. No darkness before the dawn. A world that is benign. A world where if you meet a strange towering creature in the forest, you curl up on its tummy and have a nap. Whenever I watch it, I smile, and smile, and smile.”

Even in Ghibli’s darker films—which sometimes do contain fight scenes, evil adults, and scary monsters—there’s always that undercurrent of pure, unadulterated innocence and yearning that even the coldest of souls could latch onto. Not since the classic works of Walt Disney has animation been able to fully carry that optimism, which makes it easy to see why many often consider Hayao Miyazaki to be the Walt Disney of Japanese anime.

But great animation is accomplished through teamwork, and it would be a disservice to the great people of Studio Ghibli to do a Filmmaker Retrospective on only one of its leading directors. This retrospective will chronicle all 18 films released under the Studio Ghibli moniker, with the aim of not only highlighting the masterful work from Hayao Miyazaki, but also in introducing readers to the company’s more underappreciated works from its other directors, including co-founder Isao Takahata and Miyazaki’s own son, Goro.

Before we can really delve into the real work of Studio Ghibli, though, we have to go back to 1984, one year before the studio was formed, and examine the film that inspired its creation: Hayao Miyazaki’s second feature film, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.

“After a thousand years of darkness, he will come, clad in blue and surrounded by fields of gold, to restore mankind’s connection of the Earth that was destroyed.”

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is considered by many to be Studio Ghibli’s first effort, even though it was made before the studio was formed. The film was animated by the studio Topcraft, because the company that hired Miyazaki and Takahata to make the film, Tokuma Shoten, didn’t own an animation studio themselves. Created with a relatively small budget of nearly $1 million, it was more of a test run for what the studio could accomplish in the future, but it still has all the staples of Ghibli’s best work and features Miyazaki’s favorite themes: a strong female character who either equals or outdoes the men, a penchant towards environmentalism, the conflict between innocence and the darkness of adulthood, and a fascination with the art of aviation and flight in general. It’s a simple yet engaging story with imaginative visuals, likable characters, and a gorgeous score by constant collaborator Joe Hisaiashi.

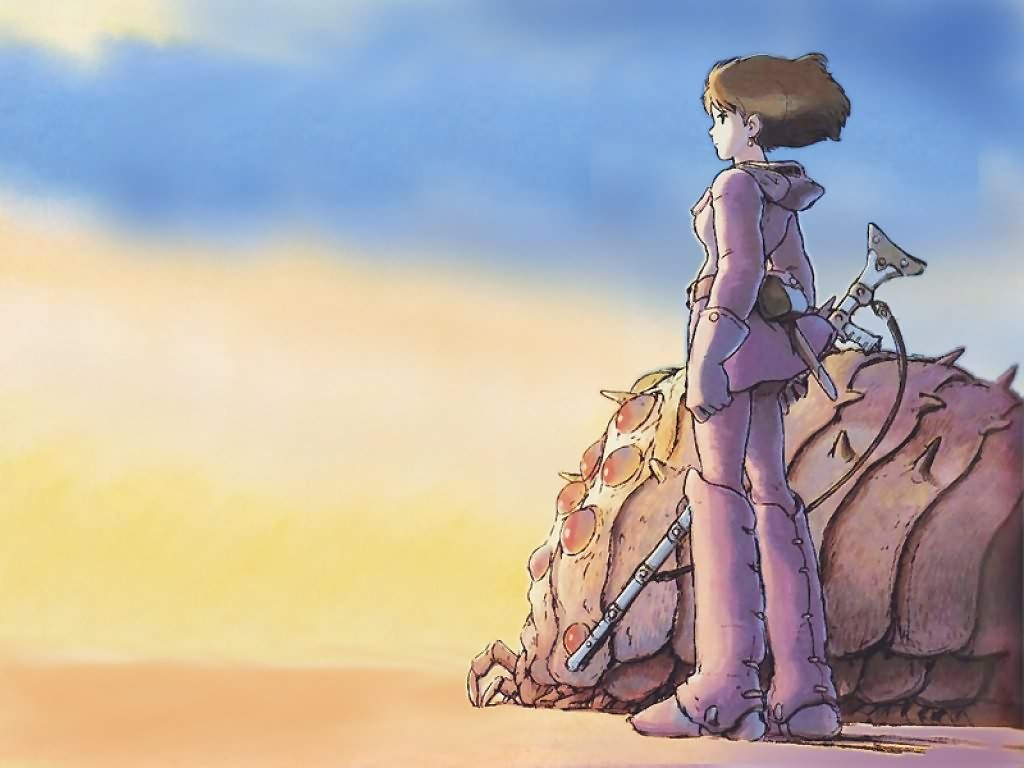

Adapted from a serialized manga written and drawn by Miyazaki himself, Nausicaä is a post-apocalyptic fantasy film that takes place in a world taken over by a “Toxic Jungle” which was formed by the aftermath of a devastating war. Dubbed “The Seven Days of Fire,” it obliterated most of the human race and left behind a sea of pollution-based spores that both kill anyone who ingests them and mutate the insects around them, creating large, insectoid beasts including the near-indestructible “Ohmu.” The last remnants of humanity are divided into settlements, one of which is home to our hero, the titular Nausicaä.

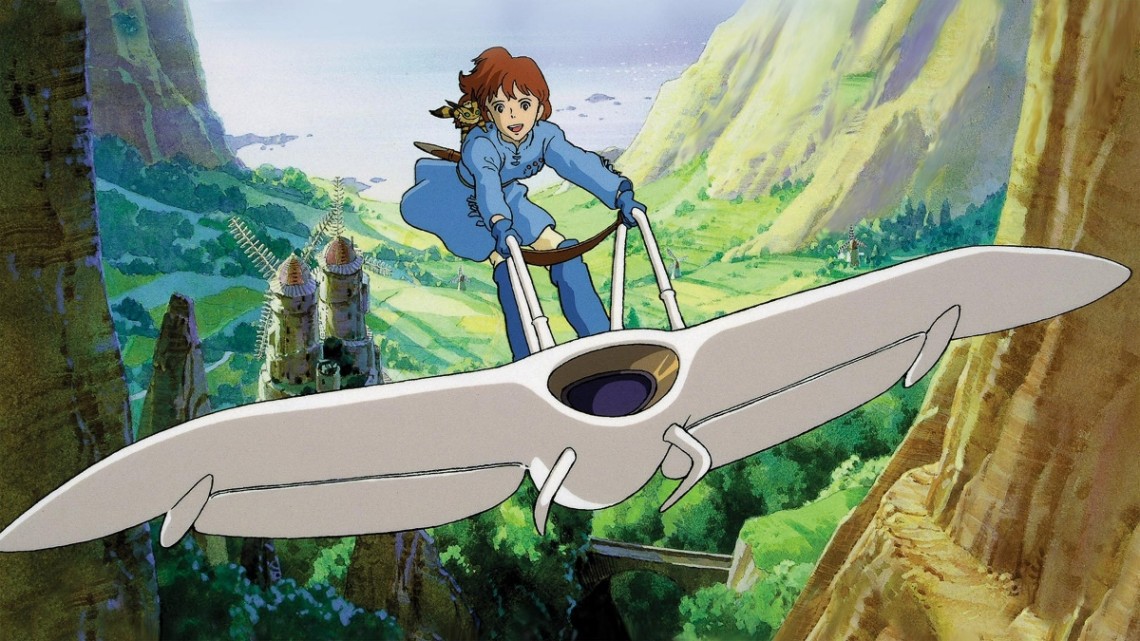

Nausicaä is by definition a “princess” (thus predating Princess Mononoke), but rather fancies herself as the contradictory combination of “warrior/pacifist.” Rather than staying in the Valley, she enjoys venturing into the Toxic Jungle on her gliding apparatus (the first evidence of Miyazaki’s adoration for flying) to study the various creatures. She devises creative means of surviving without harming or killing others, but the film’s best drama comes when she’s forced to pick a side.

The conflict between Nausicaä’s innocent, empathetic spirit and the cold survival instincts that come with living in this perilous landscape reinforces another of Ghibli’s recurring themes: the importance of embracing nature and environmentalism. Better still is that while there’s clearly a “good” side and a “bad” side, the people who find themselves in favor of survival are depicted in a nuanced manner. We can understand why they’d adopt certain strategies, even though these methods are often cruel, unnecessary, and destructive to the world they live in. While it’s not Miyazaki’s most morally complex film, it has its shades of gray that keep the plot intelligent enough for a young audience to actually learn something.

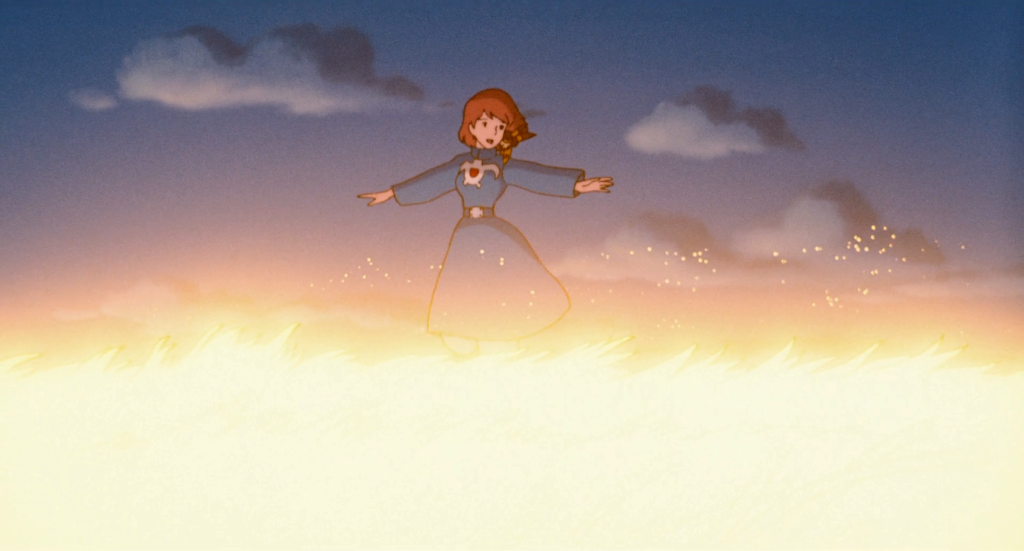

The film’s conclusion is remarkably beautiful, with Nausicaä deciding she’s willing to sacrifice herself for the good of the planet even if it means being hated and murdered by the very people she wishes to protect. And like all of Miyazaki’s films, no good deed goes unrecognized. It could’ve been a hackneyed ending, but Nausicaä’s resurrection is so beautifully animated that, when coupled with Joe Hisaiashi’s lovely music, it transcends cliché and even gives children a legitimately hopeful and enduring lesson about doing the right thing in times of crisis.

Each frame of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is lovingly hand-drawn and incredibly detailed, melding fantasy elements with “steampunk” (another recurring motif in Miyazaki’s filmography). Ghibli would continue this commitment to hand-drawn animation until the mid-90s, when Princess Mononoke was drawn with the assistance of subtle computer effects. Even today, their animation usually only utilizes computer effects when they’re absolutely required.

(And while we’re on the subject of animation, here’s a fun fact: one of the Nausicaä‘s animators was Hideaki Anno, who would later become the creative force behind Studio Gainax and Neon Genesis Evangelion. Remember that name well, because it will be mentioned later when everything comes full circle in The Wind Rises).

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is also noteworthy for being the film that ultimately dictated how Ghibli would distribute their films in North America. The original American release of the film was re-titled Warriors of the Wind and shaved off 21 minutes and 50 seconds from the original cut. Not only were various scenes trimmed to dumb down the film, but names were changed in the English dub (Nausicaä became Princess Zandra, for example), the Ohmu were made out to be monstrous villains instead of the gentle giants depicted in the original Japanese version, and the film’s environmentalist themes were almost completely excised.

The Warriors of the Wind cut was such an abomination that the studio has asked fans to erase its existence from their collective memory, and they’ve since adopted an incredibly strict “no-edits” policy to anyone wishing to distribute their films overseas. That rule was kept when the studio’s North American distribution rights were bought by the Walt Disney Company in 1996, with special regard to the notorious Harvey Weinstein’s attempt to cut their 1997 feature, Princess Mononoke. They responded by mailing him a Japanese katana and a note that simply read “no-cuts”.

Studio Ghibli was formed a year after Miyazaki and Takahata proved themselves with Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. Now a fully-developed animation studio, they were given a bigger budget for their first feature. It was another fantasy film, but of a different sort, lighter in tone and and more brimming in spectacle, but in no way skimping in the main qualities that made Studio Ghibli unique even before they were Studio Ghibli.

Next week: the birth of an animation studio and Castle in the Sky.

Previous Movie Mezzanine Filmmaker Retrospectives:

The Darren Aronofsky Retrospective