Here’s part 1 and part 2 of cinema as authorial therapy.

Many films that act as self-therapy tend to work on a certain level. Documentaries like Waltz With Bashir are literal therapeutic workings, with the author directly interacting with their own strife. Fictional narratives like 8 ½ analyze the author’s own creative skills, attempting to discover their own artistic worth through themselves, and themselves through their own artistic creation. Meanwhile, a film like Melancholia works on a more abstract level, dealing with something as general as the author’s own depression. Evolving from that are films like The Tree of Life, which deal more specifically with moments from the author’s past that they wish to reconcile with. All of these films have fixed their makers through the power of storytelling.

And then you get to Hideaki Anno’s landmark animated feature film, The End of Evangelion, which combines all these aspects.

It is impossible to consider or even understand End of Evangelion without having seen the seminal anime television series Neon Genesis Evangelion, which the film continues and concludes. Animator Hideaki Anno—who originally worked with the likes of legends such as Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, and other such animation idols—co-founded Studio Gainax in 1984 and worked on various feature films and anime series. His latest at the time, Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water allowed him little creative control, bringing him down into a period of depression that continued onto his next project in 1995, Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Created as a response to Anno’s growing resentment towards the “otaku” lifestyle in anime fanbases, Neon Genesis Evangelion was created as an attempt to deconstruct the popular “mecha” genre of anime, and otaku fans in general. Its protagonist, Shinji Ikari, was a deeply antisocial individual unable to relate with or understand others. His only means of connecting with the world around him was by piloting the show’s titular giant robots, hoping that people would respond with the affection he craved.

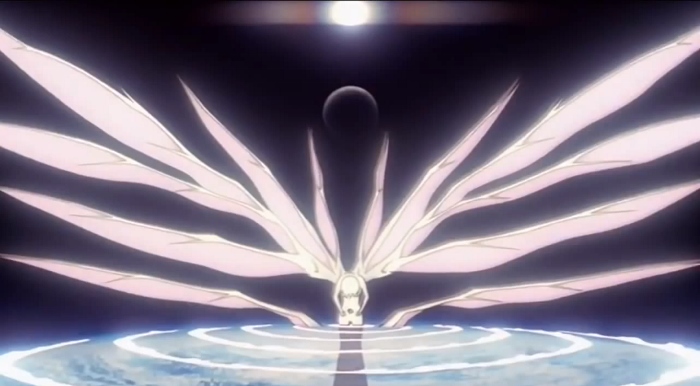

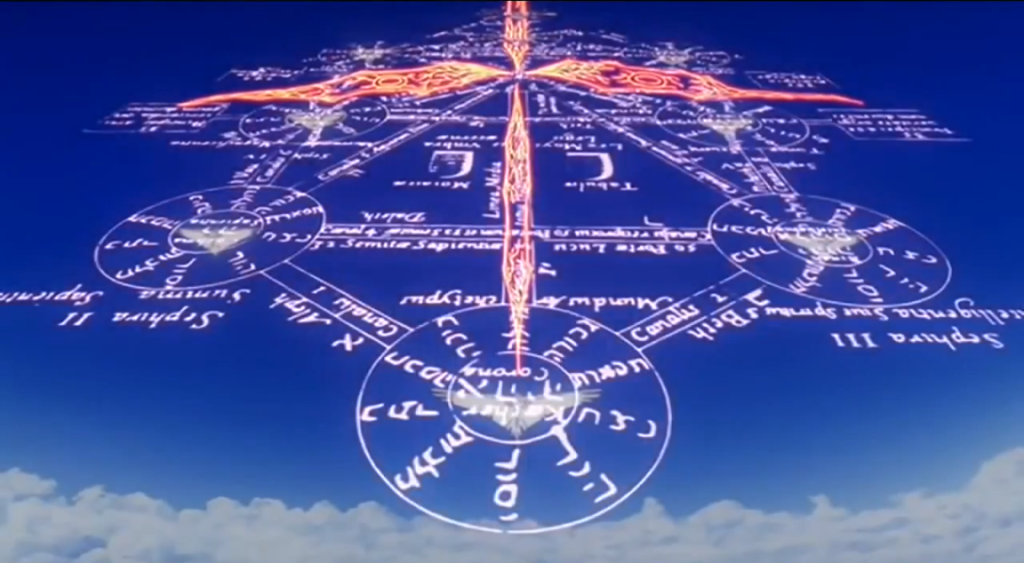

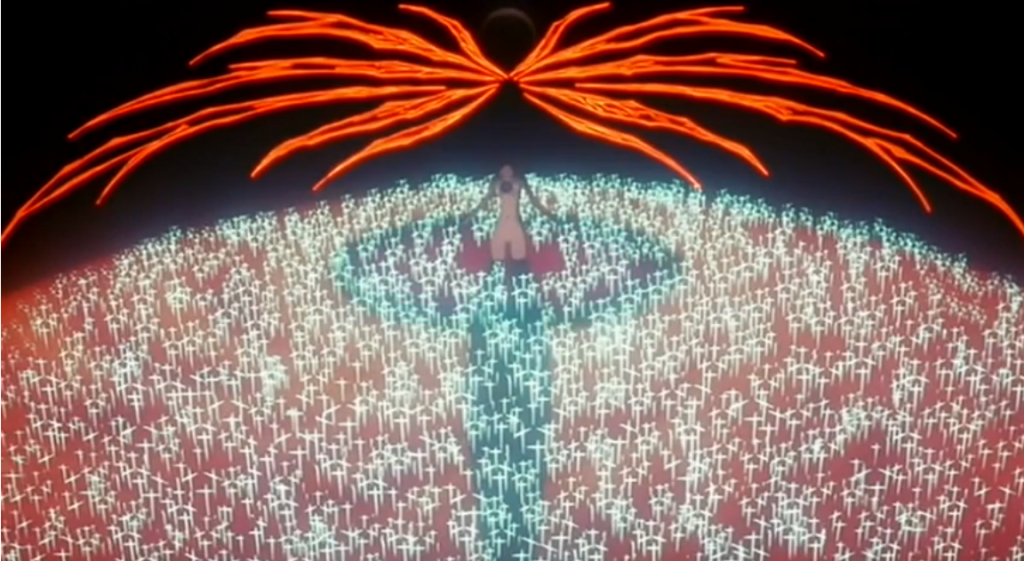

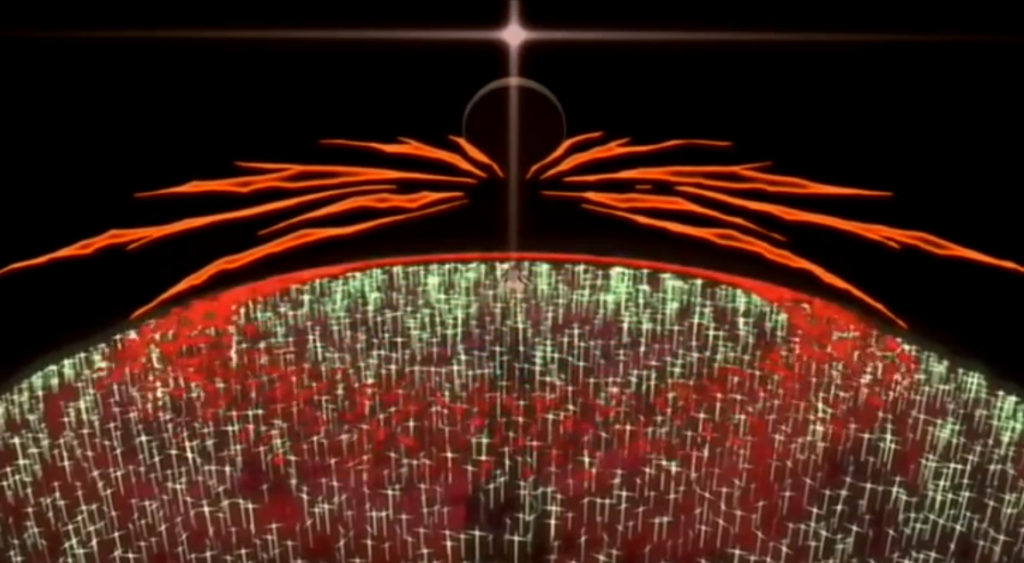

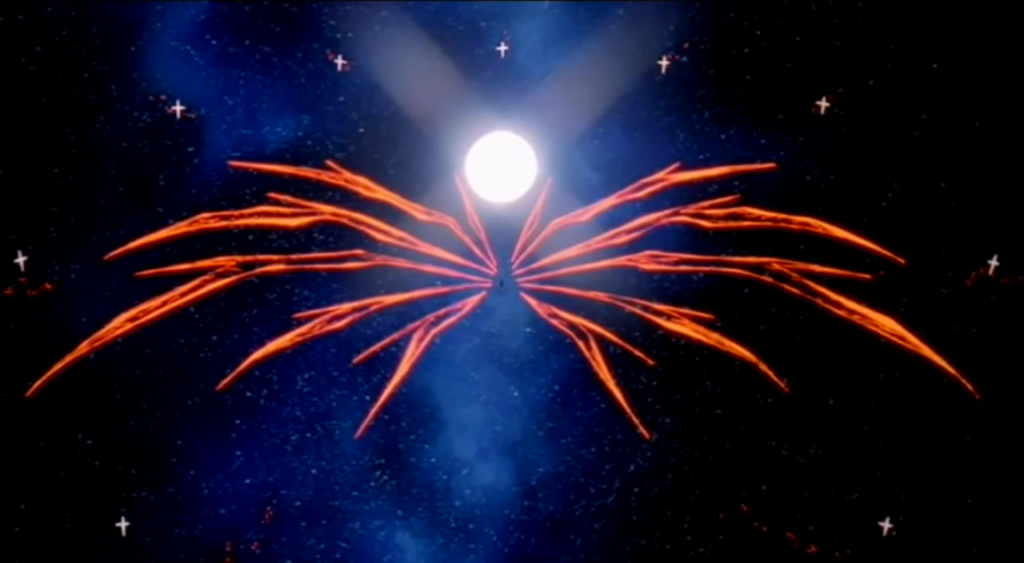

A combination of giant mecha vs. kaiju battles and Judeo-Christian iconography and terminology, the main plot revolved around a military organization called NERV in the then-far-off-future of 2015, attempting to stop an incoming apocalypse that would be caused by alien beings called “Angels”. The only means of defeating them were giant bio-mechanical beings called Evangelions (aka “Evas”), which could only be piloted by child soldiers. The show followed three of these pilots: the aforementioned Shinji Ikari, the mysterious Rei Ayanami, and the hot-headed perfectionist Asuka Langley. As the show progressed, questions regarding the origins of the Eva project, what the Angels were, and NERV’s mysterious, shadowy intentions unfolded, while also creating new ones along the way.

But various production challenges kept Anno from creating his show the way he wanted, from a constantly dropping budget to disagreements about the show’s direction, and Anno’s own depression coming back to haunt him as he received creative pressure from every angle. This caused the show to take experimental “shortcuts” with its animation, sometimes holding on still images for uncomfortable lengths, and attempting different styles during flashbacks and dream sequences. Anno was even displeased with the positive reaction of fans—the very otakus he wished to “enlighten”—who were more obsessed with facile concepts like the characters’ “cute” appearances and sexual tension.

As a response, the series became darker and more psychoanalytical as it progressed, with its child characters moving to the verge of insanity from both the Angels’ psychic powers and the constant pressure that comes with piloting the Evas. Shinji, Rei, and Asuka suddenly became personifications of Anno’s own incredibly damaged id, ego, and superego respectively, with the final two episodes becoming a series of psychoanalytic therapy sessions taking place entirely within the characters’ minds. At that point, Anno put his own creations and his audience through the cerebral wringer in order to cope with his deteriorating mental state. It went from Mobile Suit Gundam to Inland Empire territory.

The fan outrage quickly turned Neon Genesis Evangelion into one of the most controversial moments in Japanese pop-culture. Anno received a variety of responses, with fans strictly divided into love-it/hate-it camps. Anno even received multiple death threats from ex-fans. As they all cried out for a new conclusion, Neon Genesis Evangelion only skyrocketed further in popularity, warranting him an excuse and a budget to create a new ending: the one he truly intended to make and the one fans have clamored for.

Which finally brings us to End of Evangelion, which wasn’t the conclusion fans wanted, but the one they all deserved.

Created at first to appease the fanbase, it instead became the product of Anno’s disintegrating psyche, anxiety, depression, and all-around pressure from the very fans he wished to both please and lampoon with his work on the television show. Here, Shinji immediately morphs into a pure avatar for Anno’s id, as End of Evangelion‘s now-infamous opening depicts him masturbating over the unconscious body of one of his fellow pilots, Asuka, who attempted suicide before the show’s finale. Right off the bat, Anno is trying his damnedest to alienate fans from the characters they loved.

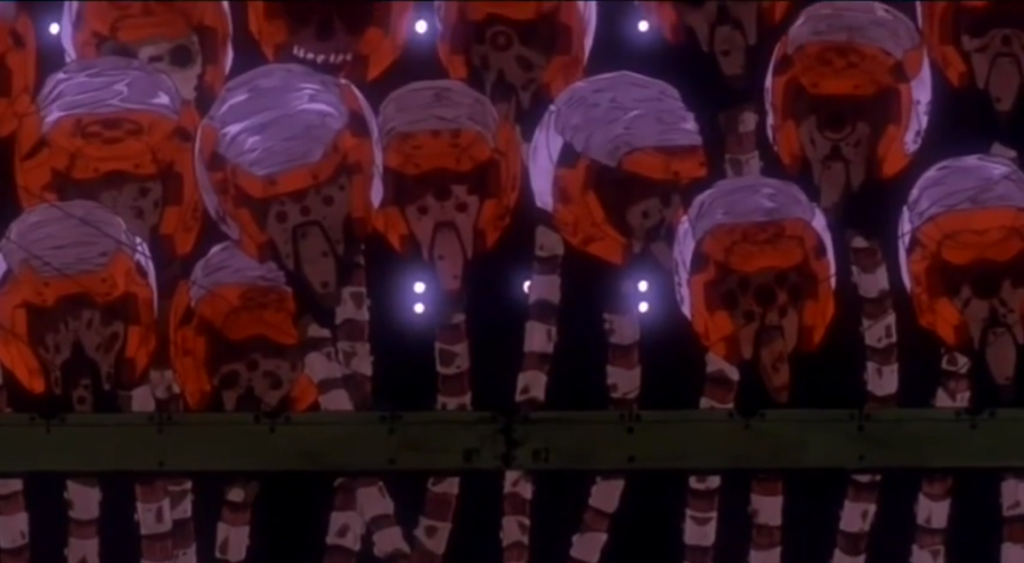

The film immediately transitions to a corporation named SEELE attacking NERV so they can gain control of the Evas and use them for a ritual known as “The Human Instrumentality Project”, which will unite all human souls and transform them into a single entity: their Angel form. “The Fate of Destruction is also the Joy of Rebirth!” they chant.

Following that is the franchise’s first real explanation for what the Angels are: alternate evolutionary endpoints for the human race. “We are the eighteenth angel,” says Shinji’s mentor, Katsuragi Misato, explaining that the human race itself has actually been fighting variations of its own future. “We could not co-exist together, even though we are fundamentally the same creatures.” It becomes increasingly apparent that Shinji’s battle with the Angels is his refusal to both mature and to empathize with others.

This truth reaches its apex when Shinji discovers SEELE has brutally murdered Asuka and experiences a mental breakdown right as they take control of him and his Eva to launch Instrumentality. Soon, the fate of mankind rests on whether or not Shinji accepts or rejects the unification of souls.

It’s at this particular moment that Anno’s influence dominates the entire rest of the picture, as Shinji picks the option you’d least expect in any other movie, but has ultimately been fated ever since Shinji’s mental state began to corrode over the course of the show: Shinji and Anno condemn (or bless) the human race to neither Instrumentality or Salvation, but instead a form of Rebirth.

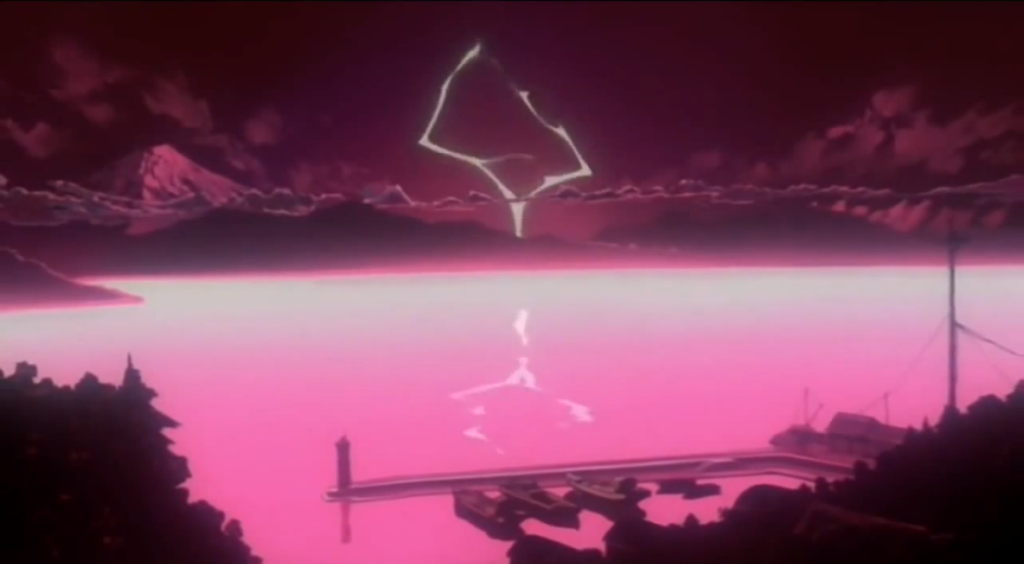

Soon, every single human body dissolves into a tang-like substance, and each soul is united into a new origin, all becoming the same primordial soup that humanity and the rest of life on Earth evolved from. Shinji would rather force everyone on earth to become one with his own form than go back to the life he had before: unable to socially connect with others, or find an individual who unconditionally loves him for who he is. In this new beginning, everyone would automatically accept Shinji, because he would be a part of everyone, and everyone a part of him. Shinji and the entire human race will, for a moment, be suspended in a state of eternal “childhood”.

“This is the very world you wished for,” Rei tells Shinji in a later scene.

The same could be said for Anno, who experienced a similar kind of social dysfunctionality when the final two episodes became so controversial. Would he rather that everyone empathized with the amount of hardship he went through to make his most enduring artistic creation? If so, would he rather that everyone have the same opinion of it? Just so he could maintain his own sense of self-worth?

At first it may seem that both Shinji and even Anno might become lost to this extended adolescence. That is, until Shinji ultimately realizes the mistake he’s made. Not in the sense that he realized he just forced unification on an entire species. His revelation is much smaller: Shinji discovers that in becoming part of the whole, he finds out how much his individuality means to him. He cannot simply confide his pain with others, because they would all be a part of him. Without pain, he will never be able to grow, evolve, or experience new things as a person, because he will be trapped in an eternally embryonic state of being. Instead of solving his loneliness, it only makes him that much more alone.

Anno himself comes to this same realization as well when the film makes one of the most jarring smash cuts arguably in cinema history: switching from the animated cacophony of souls being converted into one, and cutting inexplicably to live-action footage of an empty movie theater that suddenly fills up with a full audience—presumably anticipating the viewing of The End of Evangelion. They sit there in disgruntled silence, unsure of how to react to the images on screen. In a later scene, Anno quickly flashes between shots of all of the different fan letters that have been sent to him since the show’s finale. Some are from devoted fans telling to keep doing what he’s doing. Others are the very death threats that brought him to his meltdown. Just as Anno sees a reflection of himself on the characters he’s created, Anno finally pulls the mirror to the viewer. This is me, he’s saying. And that is you.

We could not co-exist together, even though we are fundamentally the same creatures. Only we have to co-exist, precisely because we are the same. If we can’t connect, then there is no progression in life, and thus, no worth. Not everyone will like what Anno has made, and indeed the film was just as divisive as the show’s final 2 episodes, but it is his. His creation, his psyche, his heart and soul poured into the pen and ink that make up the fabric of his strange, surreal world. It helped him grow as an artist, and it allowed him to create this masterpiece of animation and filmmaking.

In the end, Shinji and Anno reach their two evolutions: that they have to grow up, and that their lives, decisions, and creations do have worth. Not because a father-figure, a voice in radio giving orders, or a rabid fanboy said so, but because they are theirs.

Shinji finally awakens outside of the primordial “Sea of LCL”—the waters that life originally evolved from—regaining his individuality through his own will to evolve as a person. The only other entity sitting with him is Asuka, alive and well again after her grotesque murder. Shinji performs another unexpected act, and attempts to strangle her—partly out of his still-existing contempt for her and also out of his desire to confirm that his actions may still have consequences, even if no one else in the world exists.

And in a move that breaks the hearts of Shinji and most fans of the show, Asuka gently places her hand on Shinji’s cheek instead of fighting back. And just like that, Shinji loosens his grip on her neck, and experiences the warmth and affection he’s been searching for his entire life in that one, small act of forgiveness. And for him, it was all worth it.

Many argue that Anno is strangling his own fans with this movie, which still wasn’t the conclusion that fans felt they were entitled to. But in the end, there were still those people who were deeply moved by the movie. And those were the ones that made Anno’s own destroying and resuscitating of his own material worth the blood, sweat, and tears.

Prior to that scene is an exchange between Shinji’s mother and father. The father asks his wife if, in creating the Eva series, they were attempting to recreate God, in a way. His mother replies with yes, and explains why in dialogue that perfectly encapsulates how Anno found his own self-worth through his creation, and all art in general:

“Humans can only live on this planet. But Eva can live forever, along with the heart of the person inside it. It will exist even if the Earth, Moon, and the Sun are lost after 5 billion years… Even if I live alone. I will be lonely, but as long as I live…—”

“The sign that someone existed won’t be forgotten.”

That’s not just the very world Anno wished for. It’s the very world we all wish for. And it all comes tumbling down, tumbling down, tumbling down…

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BNT279MpY74]

(The above clip is NSFW)

2 thoughts on “The Very World You Wished For: On Cinema As Authorial Therapy, Part 3”

Granted the first time I watched End of Eva, I thought it was great from a cathartic perspective but on subsequent viewings I’ve kind of come to consider it worse each time. It’s cataclysmic but for the majority it favours action and its characters become very one-dimensional in comparison to the series. I see the appeal of End of Eva if from a conventional viewpoint but I think it’s mostly only there to appease people who want a conclusion to the drama. As this essay sort of addresses indirectly, the end of end of Eva is perhaps where the most interesting aspects to it lay.

I never really minded the action. While I do agree that the main focus and heart of both the show and the film has always been the characters’ psychological and emotional baggage, at the end of the day, it’s still a mecha anime (albeit, as I previously opined, a send-up of that subgenre) and one that should still satisfy on that basic front. And the reason why I think that the action-oriented scenes prior to the more heavy, surreal moments in EoE work is because it’s backed up by the knowledge that these giant robots end up becoming all they have.

Being a pilot is what brings Shinji to emotionally and socially connect with others, Asuka is able to have purpose by being “the MVP” after her mother’s traumatizing suicide, and Rei is able to partake in fitting in with the human race–which she isn’t a part of–by saving them from the destruction that she would, ironically, kickstart in the events of the film.

It’s an interesting topic though. Could action still be as much a center for true, human drama as much as more contemplative scenes? I think films like EoE are good examples that it can. While the scenes in which SEELE is attacking NERV are noticeably less interesting (mostly because they’re only there to set up the main conflict, and not much more), Asuka’s final fight is one of the highest points of the entire franchise.