Film, like all great art, is a medium that can emotionally connect with the audience in incredible ways. Outside of revealing profundities that no other art form can depict in the same way, we watch movies to fill our own voids, both emotional and psychological. The best films transcend escapism. They allow us to see the world, and sometimes ourselves, in different and vital ways.

But this effect goes beyond the audience. Some of the most fascinating, inspiring, and transcendent works of cinema have come not from a director’s desire to enlighten the audience, but instead to plumb the depths of his or her own heart, mind, and soul. Sometimes the director and/or writer—we’ll just use the term “author” for this series of articles—will look within themselves not just to find something that can universally connect with the audience, but to face the darkest parts of themselves head-on. In these cases, the author is unable to find any other means of communicating his or her emotional turmoil outside of cinema.

I find this sort of project utterly fascinating, and after recently watching a certain animated feature for the first time, I wanted to highlight some of the greatest works of cinema that were created as a means of “authorial therapy” (I’m open to suggestions for better-sounding terms, but this will do for now). This article won’t be a comprehensive list of every single film that acts on this principle; I’m just going to highlight over the course of three articles some examples that truly resonate with me as both deeply emotional viewing experiences and startlingly personal pieces of that particular author’s soul.

The most literal form of cinema as authorial therapy comes in documentary film, with the authors in question tackling what’s emotionally disturbing them in a very direct and rather literal manner. Many documentaries have done this with results ranging from masterpieces to indulgent vanity projects, but two that really stood out to me were a couple of films that could not be more different from each other in content, but use similar techniques to visualize the emotional struggle of their creators: Terrence Nance’s An Oversimplification of Her Beauty and Ari Folman’s Waltz With Bashir.

An Oversimplification of Her Beauty seems like one of those aforementioned works of indulgence at first glance. New York filmmaker Terrence Nance, after going through a break-up, compiles archival footage, letters, journal entries, and internal monologues from the time he spent with his girlfriend Namik, and uses them as the backdrop of an exploration of his own relationship and why it was that it failed. What Nance does to elevate this material, however, is combine all of those aspects with visualizations of his romantic fantasies via every single form of animation he could possibly master, from sketchbook drawings brought to life, to stop-motion, to animated paintings, and even more elaborate means.

Ari Folman’s Waltz With Bashir, an Israeli documentary about the Lebanon War, does something somewhat similar, but on a much grander, more harrowing scale, and with a more serious subject matter. Upon realizing that he remembers nothing about the Lebanon War, Folman interviews friends, colleagues, historians, psychoanalysts, and scholars alike to discover the source of his amnesia and learn more about one of the most troubling moments in recent Middle Eastern history. Folman also visualizes these people’s stories—and sometimes fantasies—through animation. His visual style is sharp and consistent compared to the experimental and sketchy variety of Oversimplification, with a look inspired by graphic novels, using deep shadows and lighting to create an ethereal, more subtly dream-like (or nightmarish) mood.

The ways in which both films utilize animation are incredibly bold, further blurring the line between memory and fantasy. By being able to visualize what can’t normally be shown with conventional documentary filmmaking, using a style that could actually do justice to these dream-like images and abstract ideas without requiring an overblown budget, these films manage to “solve” their creators’ baggage while offering something universal for the audience. Nance delves so deeply into the psychological complexities of his romance that he manages to make concrete visualizations of some of the abstract emotions we all experience throughout our own relationships. Folman, meanwhile, discovers the objective truth through numerous subjective lenses, offering something that acts as both a history lesson about the Middle East and a study of memory and the passage of time.

But of course, documentaries aren’t the only films with the capacity to rip the author’s soul bare. There have been many almost autobiographical films about the act of filmmaking itself, drawing from the author’s experiences in the field and then deconstructing them along the way. The most famous example of this is Frederico Fellini’s 8 ½, which follows a film director named Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni) facing all sorts of pressure from producers, mistresses, spouses, colleagues, and journalists alike during pre-production for his latest film. As the annoyances continue to multiply, he retreats into his subconscious where he experiences memories from his childhood, fantasies that re-purpose and “direct” the many people of his life, and various other forms of daydreaming.

Guido is very obviously a stand-in for Fellini, and many aspects from Guido’s memories actually come from Fellini’s own childhood, such as his Catholic upbringing. He recreates these details to see how it affects his own creative process, why certain themes interest him, and ultimately how it can sometimes prevent him from approaching his creative endeavors confidently. This is especially problematic when both he and Guido are constantly being pressured into crafting something that’s “true,” “meaningful” “profound,” and “universal,” when all he can do is draw from his own seemingly meaningless experiences, acknowledging his failures more than his strengths.

This culminates in the film’s bravura ending, in which, after canceling the production of his film, he has one last moment of reconciliation with his memories. Hundreds of his family members, friends, colleagues, and acquaintances—basically everyone he’s ever known in his life—all join hands as he directs them like a circus ringleader, unifying their experiences with his own to create something truly universal: a chain of human experiences. It is through Guido’s failure to create a film, a failure that represents Fellini’s own pressure and sense of inadequacies, that Fellini actually succeeds in crafting what is arguably his greatest masterpiece. He turns his fears into strengths.

Charlie Kaufman actually meta-analyzes his own abilities as a screenwriter twice. The first time is with the Spike Jonze-directed Adaptation. Unlike 8 ½, which recreates experiences and events that inspired the film that you’re currently watching, Adaptation doesn’t hide in fiction, but rather playfully melds it with reality.

Kaufman (played in the film by Nicolas Cage) writes himself into his script—a move that he himself calls “self-indulgent,” “narcissistic,” “solipsistic” and “pathetic”—at a crucial moment of severe writer’s block. While trying to adapt Susan Orlean’s (Meryl Streep) novel The Orchid Thief, Charlie fails to find a way to make a book about flowers cinematically interesting. Meanwhile, his twin brother Donald—a fictional creation who’s also a screenwriter played by Nic Cage—is basking in the success of his script for a twisty psychological thriller called The Thr3e, despite being, for all intents and purposes, a hack. (“Mom called it ‘psychologically taut.'”)

Charlie’s (the real Charlie, not the Movie-Charlie) script takes an even stranger turn when he realizes he has to change the events of the book, and thus, the real events revolving around Susan Orlean and the Orchid Thief John Laroche (Chris Cooper). This brings Movie-Charlie’s journey down a road that devolves/evolves (your mileage may vary) into the same classical storytelling tricks Kaufman abhors in the beginning of the film and which his twin Donald embodies, including as car chases, deus ex machina, shootouts, and other such devices.

Soon, Susan Orlean the real person is morphed into Susan Orlean the character, who finds herself in a romance with John Laroche. Laroche also experiences a metamorphosis in Charlie’s script: he’s not only the titular orchid thief, he’s also the only one who knows how to re-purpose the plants into psychotropic drugs. And Charlie himself ends up entangled in their story as well, forced to face these characters, and thus his own shortcomings as a writer, directly, with his other half Donald in tow.

While Kaufman may feel somewhat guilty for not being able to make a movie that was simply about flowers, his diving into his own creative process and having to adopt older and more classical means of screenwriting makes for an intriguing metamorphosis that we as the audience are able to witness, through both the meta aspect of his adapting of the novel, and of Susan Orlean diverging from her source material right before our very eyes.

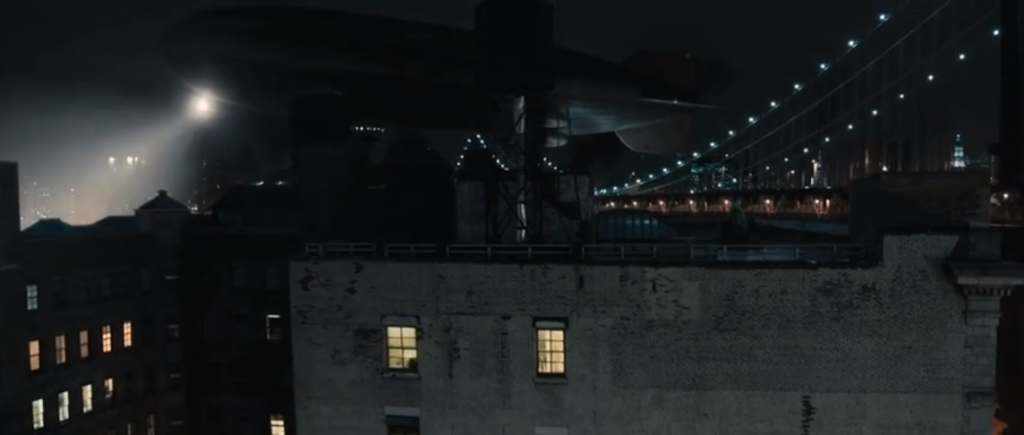

Kaufman would top that film’s meta-functional depiction of an artist striving to create something truthful without surrendering to indulgence six years later with Synecdoche, New York, the most polarizing in Kaufman’s career, and one he also directed. It follows a playwright named Caden Cotard (Phillip Seymour Hoffman) who receives a MacArthur Genius Grant that allows him an unlimited budget to create his magnum opus. To accomplish his masterpiece, he rents a giant theater the size of an entire metropolis and fills it with as many extras as he can fit, all to create the most unflinching depiction of real life imaginable: a recreation of all of New York City. He wants every single citizen of New York to be played by an extra. And those actors working in the play need to have actors playing them as well. Art imitates life, life takes a few cues from art, new art evolves from this new life, and now even more art must be made to imitate that as well.

The play takes up decades of production,with the entire city of New York being swallowed by his indulgent creation, as art and reality head toward a spectacular crash course… and is ultimately never finished as a result of Caden’s ever-expanding ambitions. The film ends on a bleaker, determinedly less hopeful note than Adaptation, with an apocalypse that leaves the city and its fake inhabitants in ruin.

Adaptation ended with Kaufman still being able to retain his signature meta-aspects while also balancing it with traditional storytelling. Through his adaptation, he discovers truths about himself and ends up delivering a story about human nature and, well, adapting. Synecdoche, New York doesn’t have that silver lining. Cotard, who is ostensibly Kaufman’s stand-in, leaves his entire creation in ruin due his own ambition. He can’t even complete his own work, and even dies along with it. By chasing truth and meaning through his art, he lived a life that was ruled by despair, sadness, and an unhealthy obsession with recreating his sorrowful past over and over again.

That’s what made it such a divisive film. By allowing itself to be swallowed by its own indulgence, is the film worthless? Or does the film organically use that indulgence as a necessary part of its statement about the tenuous relationship between art and reality? Let’s hope we continue arguing, because it’s a debate worth discussing.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EHeyI28UQqQ]

In the next article: Lars von Trier deals with his own depression, Darren Aronofsky works through the five stages of grief, and Leos Carax and Terrence Malick both reconcile with the tragedy of suicide.