Whisper of the Heart. What a lovely title for a story. Simple, poetic, and evocative of how beautifully transient the simplest of moments can be. It also best describes the appeal of Yoshifumi Kondô’s short-lived legacy as an animator: he came and went like a whisper in the wind, but in that small voice came something deeply human and unforgettable.

Throughout the Studio Ghibli Retrospective, I’ve thus far only written about films directed by the two co-founders of the animation company, Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata. Yet it was clear from the beginning that they weren’t the only two singular talents in the studio. Their company housed hundreds of hard-working animators, and as you’d expect, most background animators tend to have aspirations towards fulfilling their own works.

One of the most promising of these animators was Yoshifumi Kondô, who worked on the animation for many of Ghibli’s films and finally got his chance to direct: adapting a serialized manga titled Mimi o Sumaseba. After the end result, Whisper of the Heart, was released in 1995, Kondô was expected to become one of the studio’s next top-tier animators, and perhaps an eventual successor to its forebearers. That day never came.

In 1998, three years after his directorial debut, Yoshifumi Kondô died of an aneurysm, though many, including Miyazaki, claim that it was the result of career pressure and overworking. The death caused quite a stir at the studio, with it even being the reason that Miyazaki announced his retirement, only to recant for the third time in his career. Instead, Miyazaki simply decided to work at a more moderated pace than before, taking three to five years to make his projects instead of the usual one or two.

Kondô’s death became both a looming and prophetic presence over the studio. He died out of his own hard working commitment and passion for his art, which became a theme in a few later Ghibli films (including their most recent, The Wind Rises) and was part of what Whisper of the Heart was about. While the film was yet another big hit in Japan, it’s still one of the most underappreciated films to come out of Ghibli here in North America.

Like many Ghibli films, Whisper of the Heart is a coming-of-age story, but of a different sort this time around. Rather than focusing on familiar Studio Ghibli themes like the loss and endurance of innocence in an age of cynicism, Whisper of the Heart hones in on more psychologically specific aspects of childhood: the passions that come with creativity at a young age, and the yearning to grow up and expand your horizons while the rest of the world is moving too slowly. It”s fitting that Miyazaki and Takahata thought of Kondô as a potential successor to their legacies, because Whisper of the Heart feels like a bridge between the two animators’ styles: the imagination and whimsy of Miyazaki meeting the more realistic depiction of Japan found in most of Takahata’s work.

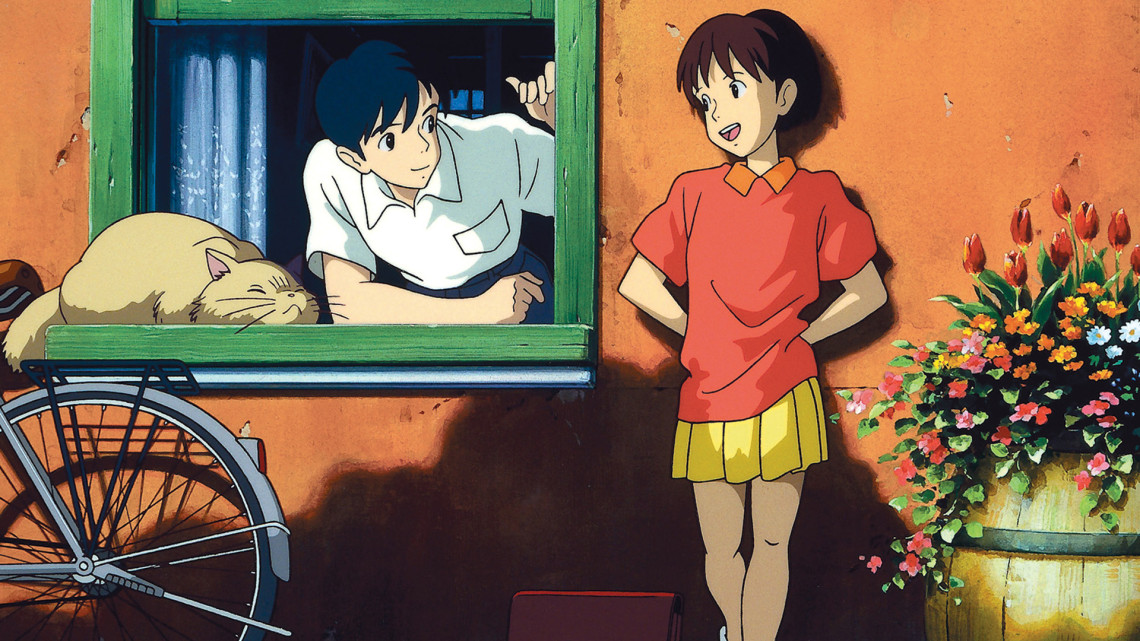

The film follows middle-schooler Shizuku Tsukishima as she’s nearing her graduation. She’s a bright kid living a simple middle-class life in Tokyo who goes to class, hangs out with friends, gossips about who’s dating who, and entertains the fantasy that something more interesting could happen to her — like something out of the many books she likes to read for fun. She gets her wish when she follows a stray cat to an old antiques store and meets a boy who wants to become a maker of violins, and their lives hurdle together as a result.

The genius behind Whisper of the Heart is how deceptively slight it is. You can’t quite blame anyone for watching the first half of the film and thinking it’s just a simple teen story, but when it eventually blossoms, it doesn’t cram your face in heavy melodrama. Instead, it gracefully segues towards a deeper understanding of how these characters desire to transcend their simplistic lives.

The main conflict comes when the boy Shizuku likes, Seiji, moves away to Italy for two months so he can become an expert violin craftsman. Realizing he’s moving forward with his life while she’s slipping away into the recesses of childhood, Shizuku decides to test herself by trying to make a work of art of her own; in her case, writing a story. Kondô’s depiction is a very specific one: the creative teen who already wants to specialize in art before even reaching college, filled to burst with ambition and ideas but lacking the life experience necessary to accomplish such a task. (These themes especially hit home for me because, really, you’re all lucky that you can’t find my early attempts at writing short stories on the internet anymore).

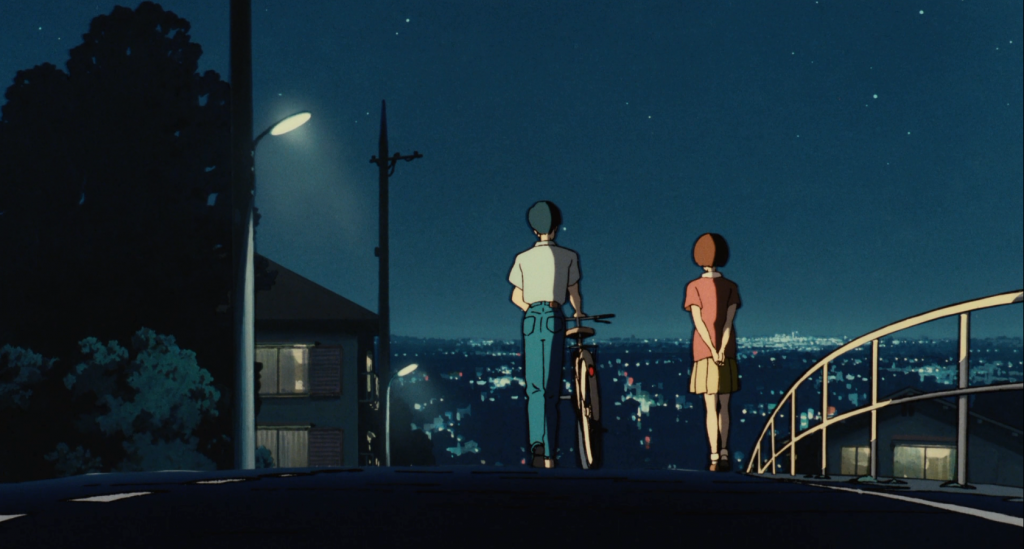

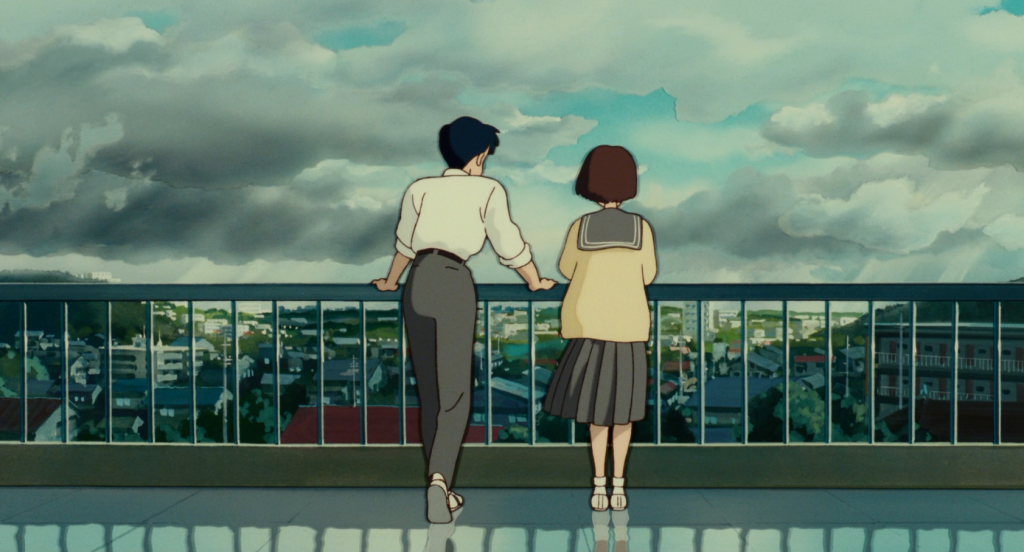

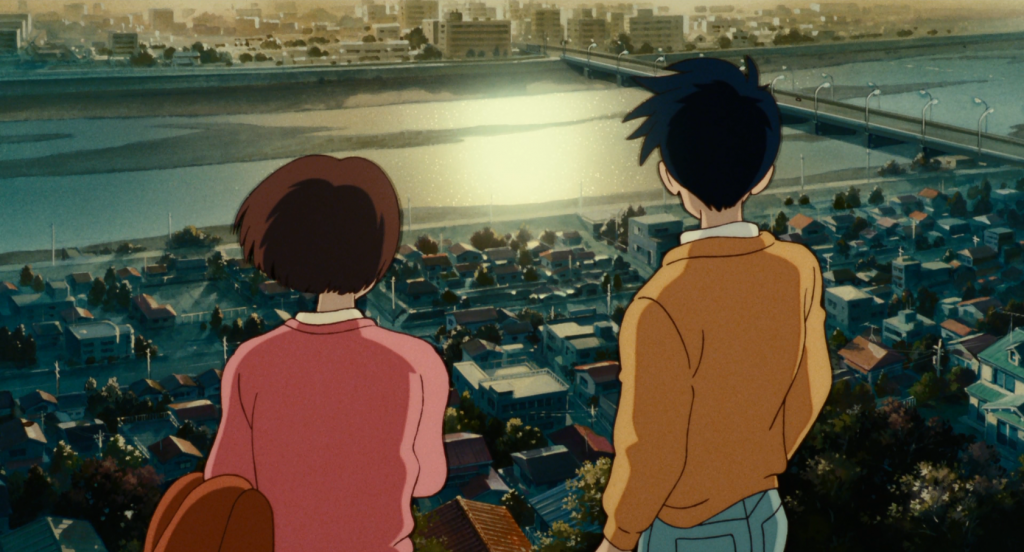

Kondô visualizes her almost hopeless battle through his lovingly detailed depiction of suburban Tokyo, as Shizuku is constantly ascending and descending its hilly environment, stressing how easy it is to move downward and the amount of effort it takes to move up. He even manages to create a subtle visual motif out of Shizuku and Seiji staring out at the horizon by utilizing a similar shot three times: the first with a low angle mostly looking up at the faraway stars, the second with a level angle that has the buildings and trees overtaking the sky, and the third and final time during the film’s conclusion, with a high angle that looks down at the houses and a river reflecting light from the sky they once knew. Right away, Kondô displays a strong yet restrained mastery of visual language that you rarely get with animated or even live-action films.

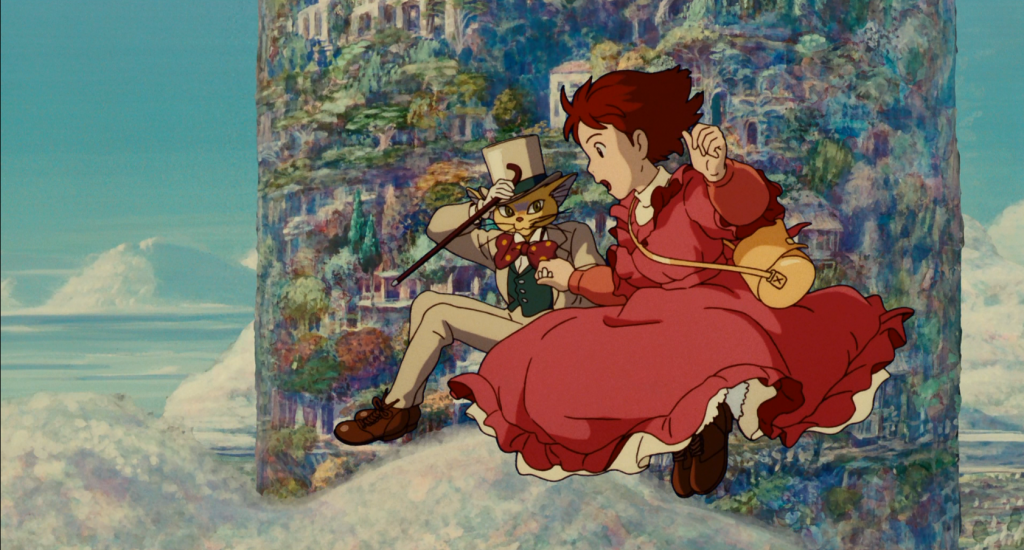

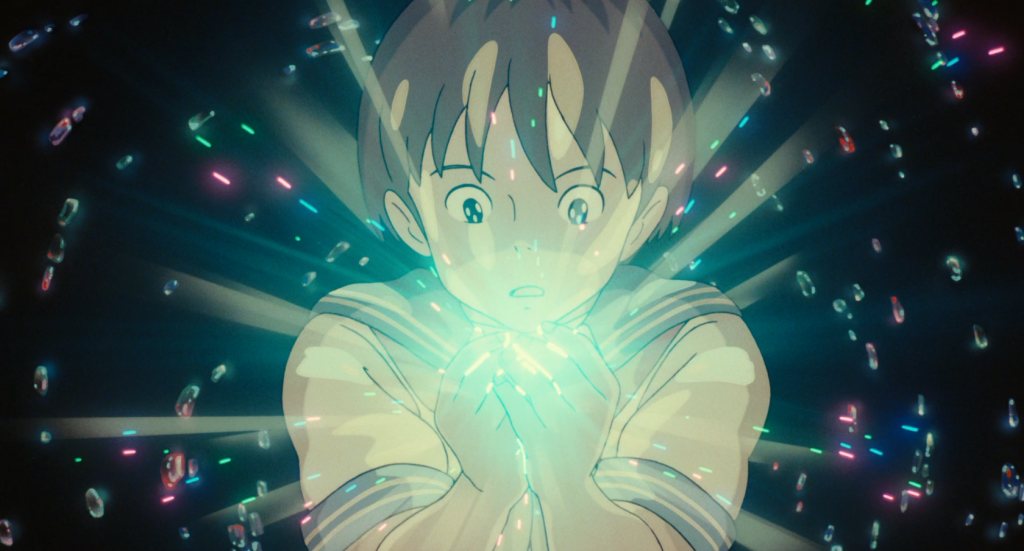

Kondô’s drawing aesthetic manages to be both simple enough to never overwhelm the senses and also rife with tenderly observed details from everyday life. It’s just naturalistic enough while also allowing brief flights of whimsy. The only time Kondô uses a more magical, Miyazakian aesthetic is during Shizuku’s brief excursions into fantasy as she’s writing her story, a fantasy about a talking anthropomorphic cat hoping to reunite with his lost lover. These scenes manage to be imaginative enough to perhaps fill a whole movie (and in a way, it kinda did) while also being so brief that they don’t disrupt the flow of the film or distract from Shizuku’s inner conflict.

Their slight, ephemeral presence in the film also speaks to the fleeting euphoria that creativity can adopt. While there’s no emotional or psychological high quite like being inspired to create, it’s hard to maintain that once the realities of everyday life wear down on you. The film gets this without needing to dive too deeply into heavy drama. Shizuku’s grades and relationships suffer as she spends more and more time writing. She’s so determined to prove to herself that she can create something worthwhile that it nearly destroys her.

Having now seen the film after two viewings of The Wind Rises, I find that this film might be the most direct companion to Miyazaki’s swansong, even moreso than Porco Rosso. Both films are about what one has to sacrifice to fulfill a dream, with Whisper of the Heart‘s smaller coming-of-age elements being a fitting precursor to the high stakes of The Wind Rises‘ WWII setting. Whereas Wind is more concerned with the moral ambiguity of creation (“Would you rather live in a world with or without pyramids?”), Whisper‘s approach is primarily focused on how those sacrifices are an essential part of growing up. The film’s metaphor for that theme–of a stone being polished continually until it becomes a gem–isn’t particularly subtle, but it’s fittingly told and gracefully written, especially for a children’s film.

The resolution for Shizuku’s hard work is deftly handled, as the film never shies away from harsh reality, but it also doesn’t punish its character with tragedy, nor does it undercut the beauty that comes with it. The film is both fair and forgiving, as best exemplified by two wonderfully written scenes.

The first scene involves Shizuku’s parents confronting her about the state of her grades. She insists to her mother and father that she’s not failing her classes because she’s working less hard, growing more dumb, or rebelling against authority. She calmly describes to them that she’s working harder than she ever has as a means of “testing” herself and fulfilling her aspirations. In a way, she’s preparing herself for adulthood more through this experience than she is through her schoolwork. What’s key to this scene is the parents’ reaction, which feels both authentic and genuinely understanding. It’s clear that they are definitely still worried about her grades, but they also understand how serious Shizuku is about what she’s doing and don’t dismiss her feelings, allowing her to continue with her writing while also stressing how she has to put more effort into school if this “test” proves unsuccessful.

The second scene is when Shizuku finally finishes her story–entitled Whisper of the Heart, of course–and shows it to the old owner of the antique store. She expects the old man to be harsh and say something negative. His actual response, however, is–as mentioned earlier–fair and forgiving. When he tells Shizuku her story is very good, she is quick to disbelieve him, insisting that it’s not actually good and she’s too young and simple-minded to make something worthwhile. He responds, “Yes, it’s rough, blunt, and unfinished, just like Seiji’s violin.” He knows that she’s obviously not the greatest writer in the world, but at the same time, encourages further development and recognizes hard work when he sees it. He’s a perfect mentor for Shizuku, and I can see his words inspiring actual children who watch this film.

Like its characters, the film’s horizons expand further and further as it progresses, creating an all-encompassing portrait of childhood dreams and the sacrifices we make to commit to them. Perhaps it’s because it really takes its time to naturally get to that point that the film isn’t as widely known as Totoro or Grave of the Fireflies are in North America, but this is easily one of the most touching and complex works to ever come out of the studio, and one of my personal favorites from them as well.

It’s eerily prophetic that Kondô’s first and last directorial effort is about pushing oneself further and further to grow emotionally and artistically, when Kondô himself made the ultimate sacrifice that comes with it. Now we’ll never be able to see how he would have grown further as a director, much like how Shizuku and Seiji’s story ends with a promise that we never see to the end. We can only assume that these wishes will be fulfilled, but real life isn’t as forgiving as the comforting confines of a Studio Ghibli film. At the very least, Yoshifumi Kondô really did manage to knock it out of the park with his first feature, and while it’s a shame that we’ll never get to see him develop as an artist, there’s a bit of beauty to a promise unfulfilled only by a pause in time (in the case of Shizuku and Seiji’s final promise leading directly to a smash cut to credits) or a meeting with death (the unfortunate end to Kondô’s career).

At the very least, Miyazaki and Takahata were still able to continue developing and blossoming as artists for a good while, with the studio adopting new digital technology to supplement their hand-drawn animation and entering their second phase of work. Next time on the Studio Ghibli Retrospective, we return to Miyazaki as we move on to his most epic, grandiose work: Princess Mononoke.

Previous Editions:

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Previous Movie Mezzanine Filmmaker Retrospectives:

The Darren Aronofsky Retrospective

5 thoughts on “The Studio Ghibli Retrospective: ‘Whisper of the Heart’”

This is inspiring! Great post.

Pingback: The 12 Heroines of Christmas ~ Shizuku | I Wish I Lived There

Pingback: Mon top 10 des films des Studios Ghibli – Passion Japonaise

Wonderful, detailed review of what is, I believe at the present, my favorite Studio Ghibli film. I have just purchased the movie recently and am excited to see it a second time.

One of my favourite movies – great review.