Due to the elusive nature of Diaz’s works his films are very difficult to find unless you’re looking or living in the right places. The ones who are lucky enough to stumble upon his pictures often find themselves with nothing more than VHS tape level of quality videos replete with missing subtitles and hazy borders. On top of this, his runtimes often exceed the bladder-breaking-point continuum and are generally only selected by the most courageous festivals and Easter European television channels for 3 A.M. showings. So while this is bound to be, ostensibly, the largest retrospective of Lav Diaz on the net in terms of films considered (possibly and probably wrong) there are still some big gaps, which are these:

Burger Boys, 1999

Woman in the Wind, 2011

Elegy to the Visitor From the Revolution, 2011

Florentina Hubaldo, CTE, 2012

However, god willing, I’ll update this when I crack through the underground tunnels and mines to find them.

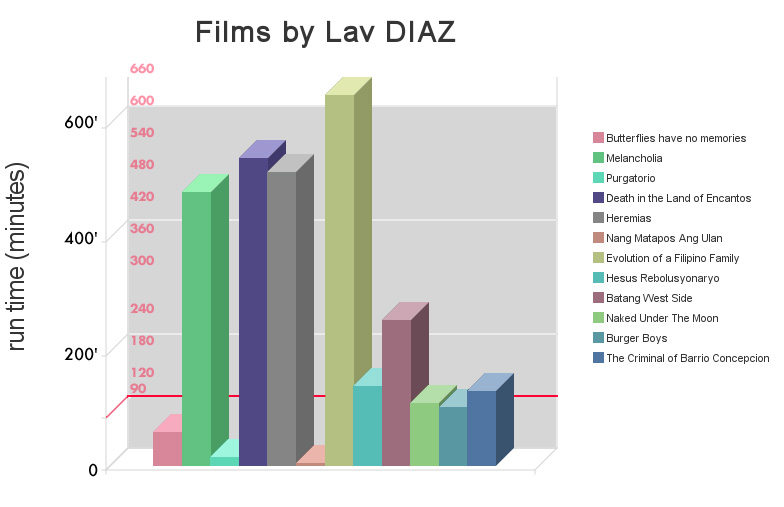

Above is a simple chart to illustrate just what you’re dealing with here, the little parts representing his short films. And so just like “Infinite Jest contains” a foreword by David Eggers telling you not to be afraid of it and to embrace the interminable chaos, the work of Diaz tends to need something similar to help convince those staring at his work with squinted eyes. The runtimes for his films may daunt those who aren’t used to his soporific values. Combine that with his leniency to Filipino ethics and socio-politial problems, and you have an even more intimidated viewer. But the fruit in Diaz’s intransigent trees are large and luscious, and his laconic length is an imperative factor to his potency. It’s important to see that this isn’t just length and stride for the sake of it. Diaz dislikes the 90 minute borderline as much as he likes rain, but his films run until he’s found his ending, whether that be at 90 minutes or 20 hours.

No matter what qualms the producers or juries or customers raise, Diaz does Diaz. His refusal to bring Batang West Side *down* to 3 hours should speak wonders to his cinematic intent. He’s a man who won’t back down, and every non-first world country wishes they had a Lav Diaz to champion them. While it may be true that filipino ethnology plays a central part of everything Diaz has touched, it is individuality that remains the universally presented chess piece. His films circumnavigate the lost and damned, the uncertain and unclear, the troubled families and silent stragglers, the seemingly unchangeable changing. So jump in and get lost. In my attempts to coalesce with the filmmaker, I found this quote from Diaz to be particularly revealing of the artist behind the camera:

“Like I said, my works are very particular about the Filipino because that’s my culture. But I don’t make films for Filipinos. I make films for cinema, as art is all encompassing. There are no borders. I don’t believe in borders anymore. It’s the same as your belief that there are no nations. I can live anywhere in this planet and I can truly assimilate in time in other cultures as well. And I can embrace these cultures all the same. But in my work, I believe that I must represent the culture that molded my being and my responsibility is to help it grow and be part of a bigger growing culture. Cinema is my medium. My films are not long. They are free.”

Here begins the journey of the increasingly illustrious Diaz, it wasn’t always sunshine and eleven hour films, but it was always something.

…

The Criminal of Barrio Concepcion

Year: 1998 // Grade: D

The Criminal of Barrio Concepcion can hardly be called a grand experience, hardly an example of the potent artist stumbling out of the barracks with his pockets brimming with masterpieces, no, this is one of those “started from the bottom now we here” type of deals. Though through its hypnotizing window one can see the periodic latent intensity of post-Batang Diaz, the artist trenchcoated in the shadows of an unseen dark alley, just waiting for opportunity to strike. The only available copy of Barrio Concepcion is frizzled and fried much like the majority of Diaz’s early works, them not being the most alluring films to immediately revitalize to the common man, though in some alluring, assumingly non-intentional way it begins to work for his aesthetic, all beginning to encompass this nostalgically endearing ambiance.

The crisp 240p visuals and distorted sound only add to the cinematic poverty but there always remains a charming presence within it, as if being sporadically brought back to lens-flare ridden childhood perpetually re-watching home-movies on an old VHS. Barrio Concepcion looks and feels like a TV film because of this, its tiring assortment of melodrama and twists and orchestral string music and excessive over-acting only move further to enhance this feeling of shoddiness. Now, circling back to the intrinsic lack of information that Diaz’s films have, this very well could be a made-for-TV film and I’ll have to take that embarrassment in droves when the time comes. Still it’s difficult to see many things here that would encompass the revered Lav Diaz of late, this circumnavigation of TV film ideals seems a far-cry from the languid building blocks of his later ten hour masterpieces. But at just under two hours this is Diaz’s shortest film, but not very Diaz.

Naked Under the Moon

Year: (1999) // Grade: C+

Naked Under the Moon incorporates the same—perhaps unintentional but lets not conclusion jump—eroding VHS tape aesthetic as his previous film Barrio Concepcion, though this is heaps above more ambitious and dignified in nearly every other regard. The melodrama, exasperated gasps, hokey orchestra, and twists are diminishing and rightfully so; there’s an attractive and refined film inside this VHS aesthetic and it’s palpable. A precarious appearance but far from precarious film-making, Diaz knows what he’s doing even if he’s moving within the parameters of producers hearing, he’s been beating his drum since day one but before Batang West Side it wasn’t quite as distinctly out there; the proliferation of the “filipino soul” is the beat to which each step he takes adheres to.

Its largely languid nature is evident from the silent beginning of a not-so-picturesque drive through a barren landscape. Though, this is still far and away from the temerity of current Diaz for better or worse, its cosy fluidity is immediately easier to grasp onto than his obstinate ten hour pieces of similar intent. The core dynamics are beginning to permeate actual humanity instead of made-for-TV melodrama here, seeping with dislocated faith—the ex-priest at a loss with his meaning stands out—and itinerant enigmatic dreams of nightmarish pasts, contrasting differing family members inevitably returning to their anhedonic addictions, this is a film that hits hard but too sporadically to leave any long-lasting bruises, but frustratingly its potential is ever-present. Sleepwalking through the hazy blue moonlight was made for the crispy VHS aesthetic, and the VHS aesthetic might just be made for Diaz.

Batang West Side

Batang West Side

Year: 2001 // Grade: A

It’s a cinematic injustice that Diaz’s films are being treated so poorly in terms of distribution, and Batang West Side might just be the biggest victim of all his films. Diaz himself has stated that he is absolutely fine with his films being shared online via whatever means, yet this helps very little, as all there is to be shared are crinkled and demolished remnants of his forgotten masterpieces. His ravenous audience is only so lucky that is voice screams loud enough to alleviate the crinkles and creases and break through into the eyes and ear of the viewer regardless. Yet with a film as phenomenal as this its recommendation comes with a drove of asterisks, that the same raucous loop of suffering will have to be taken. But then we must abide, as unwanted as it may be, to the saying “better to eat from the floor than to go starving”, and wait for the Criterion’s and Artificial Eye’s to save us.

Breaking free from both commercial filmmaking and any back-of-the-mind thought that his obstinate length would not be well received, *this* is Diaz’s breakout film. Which isn’t exactly something that seems blatant, what with how badly Batang West Side has being treated over the years despite Diaz’s increasingly protruding status. This is his first foray into a world of cinema without deadlines and limits, and boy does it show.

Batang West Side works as an unseen sixth season of The Wire that centers on the integration of Filipinos into the criminal circuitry of western culture and their forlorn attempt at escaping it. But this time Mcnulty’s more lost and alone than ever. There’s no love and no bunk and no sign of rescue, the quirks of its inmates fade quickly among the snow infused rubble. It’s all in the game though, right? Diaz is so passionate in his tumultuous journey to proliferate the identity and individuality of a Filipino cultural consciousness that the humanity is etched into every street corner his camera touches. His love and enthusiasm for cinema as not only art but as a responsibility to culture will be remembered highly when gazing back on this opus.

Here Diaz slowly carves the life of an alienated and disconnected youth over the stormy five hour length, think Citizen Kane with a twist of Rashomon, but here rosebud is the lingering smoke of a freshly charged pistol. The director both unravels the story and himself simultaneously as he spirals down into his own demons of frostbite and distanceless darkness, remaining just as unsure with himself as he is with everything that surrounds him. The length is unequivocally justified, a giant of Diaz’s opus that doesn’t feel purposefully elongated in the least, every scene has impact and imperative and time to digest the events is left to a strict minimum in comparison to his later beasts. Calling a work of Diaz velocious or aggressive might seem insane to people who’ve borne witness to his more sedated enterprises, but here the tightness is palpable, during it’s entire 5+ hour runtime there’s barely a fault in its entirety outside of its malnourished quality. As climax closens, detective and filmmaker meet, both of whom are Diaz, fervent and lost, afraid and determined.

A lone man staggers around a deserted highway crossroads under the opalescence of the night sky contrasting the bright lights of the city, his thoughts loud and catastrophic, though for one brief moment we see them dissipate, replaced with determination to hear nothing other than the scrunch of freshly layered snow as it meets the human foot. Five hours later we circle back to what we began with, another shadow hopelessly strewn across the futile concoction of white snow and dark skies.

One thought on “The Lav Diaz Retrospective”

Amazing film-maker.