“The wind is rising! … We must try to live!”

~Paul Valéry

The Wind Rises may be classified as a “biopic,” but it is less a document of a man than it is of a dream: beginning with its birth, progressing through its lifespan, and then finally waving a tearful farewell to its cruel yet beautiful demise. Much has been made about how this is Hayao Miyazaki’s final feature, while others — who were quick to point out that Miyazaki announces and then recants retirement after almost every project — didn’t believe he’d actually follow through with it.

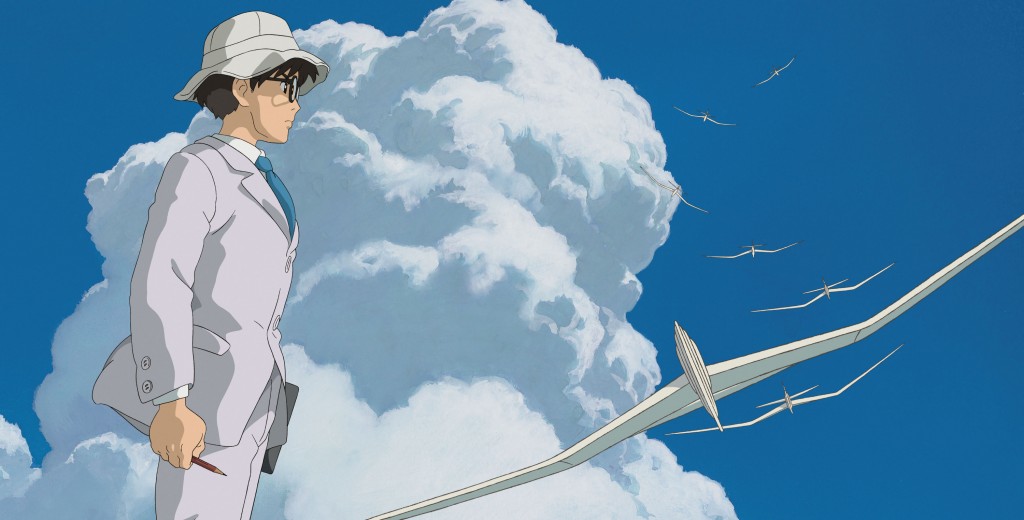

But if a case is to be made that The Wind Rises is, in fact, his last film as director, then it would be that, unlike Spirited Away or Howl’s Moving Castle, The Wind Rises is emblematic of, if not the evolution of a career, then the end of one for sure. It is the rumination on an entire career creating art, on seeing it commercialized, and whether or not it’s all worth anything, really. Furthermore, The Wind Rises is a culmination of all of the themes that fascinate Miyazaki, even if it has little in common with the rest of the director’s oeuvre, structurally and narratively.

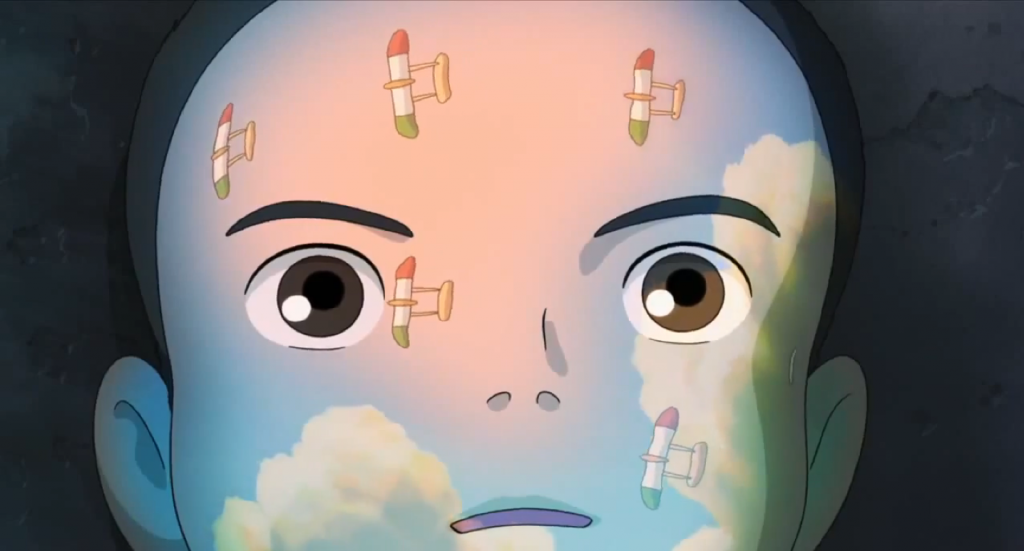

Only two of Miyazaki’s other films have taken place in the “real world”: Porco Rosso and My Neighbor Totoro, and even those featured elements of magical realism. The Wind Rises, on the other hand, is based on the life of Jiro Horikoshi, though heavily fictionalized. It also approaches its story differently. Miyazaki’s films usually have melancholic undertones, but in The Wind Rises they take the foreground. All of his previous films were carefully paced, making sure that even quiet, uneventful moments had clear drive. Each scene in Kiki’s Delivery Service or My Neighbor Totoro is like its own little short film, and they all cumulate towards a whole.

By comparison, The Wind Rises is more meandering and subdued. Instead of each scene being its own whole that’s also part of something larger, the entirety of The Wind Rises is treated with a combination of Miyazaki’s humanism and the cold, existential fatalism of a director like Kubrick. The film is constantly and continually reconciling the fact that these scenes are all meaningless in the grand scale of existence with how the characters find meaning and emotion in them anyway. It’s a film of artistic discovery, but also one of weariness and exhaustion. The more they try to stave off the inevitable, the greater we see the side of meaninglessness.

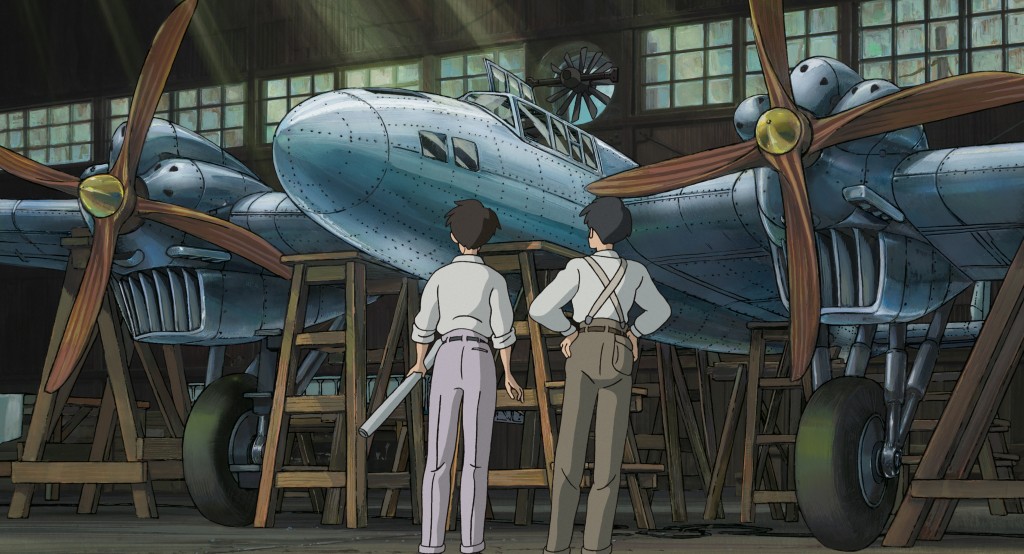

Horikoshi was an engineer who designed fighter planes for the Japanese during World War II — planes that would eventually be used to slaughter not only Americans at Pearl Harbor, but also the Japanese pilots inside of them. At first, Jiro is indifferent to the manner in which his designs are to be used. Upon wishing to finally become an engineer as he grows older, he realizes that the only means of doing so professionally requires doing it for the military. But that’s okay so long as he can keep his original designs, artistic intent, and be given the proper materials to realize his visions. But compromises continue to be made. The Japanese aero industry can’t afford the kinds of expensive materials that the rest of the Axis Powers have. Jiro’s designs can only be flown without the burden of guns being strapped to them. The only way to even carry the monstrously huge airplane parts is to tow them via oxen because Japan is too poor to afford proper trucks.

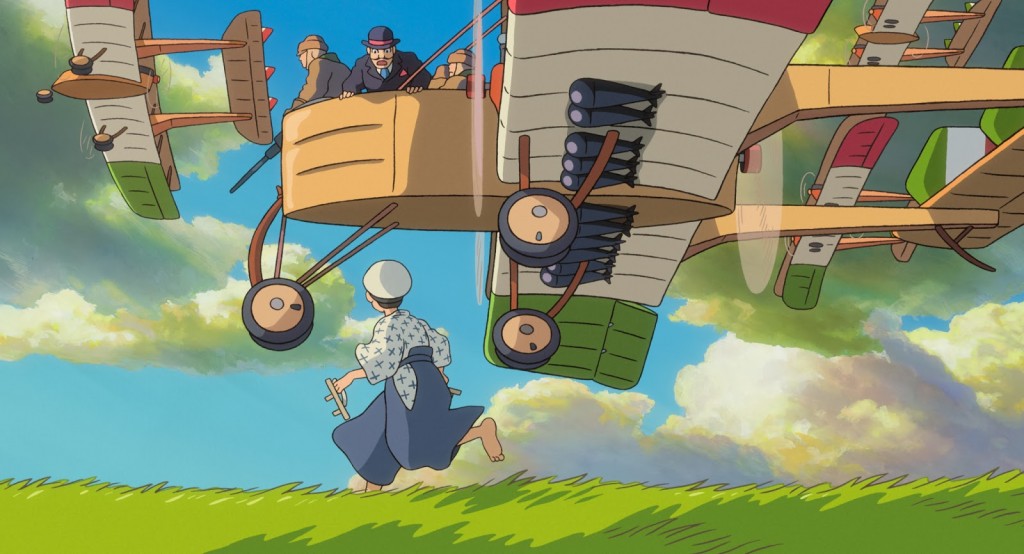

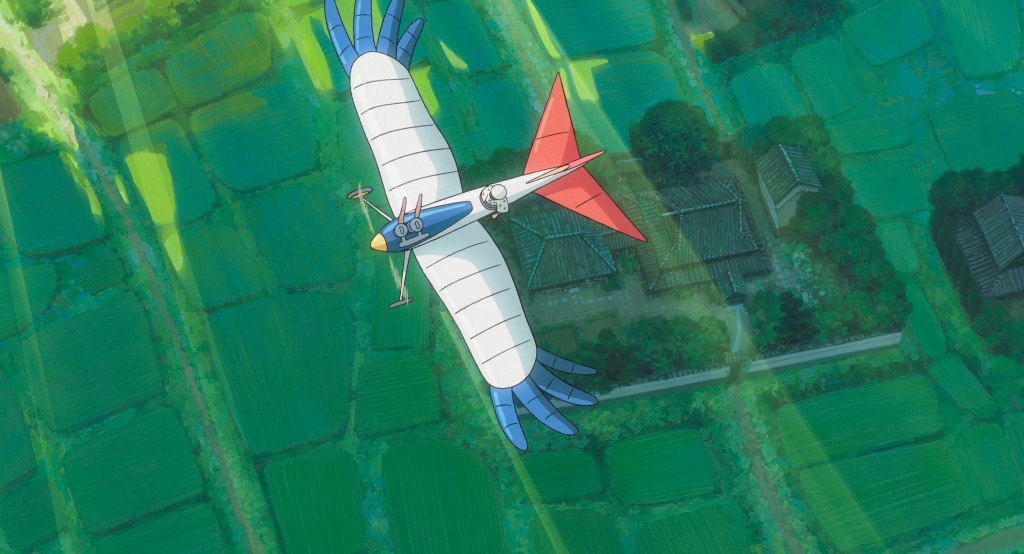

Jiro treats the vehicles not as products or weapons, but as art. When we see him draw the designs on his graph paper, it is akin to, well, the way an animator would materialize a character. Miyazaki draws art of Jiro drawing art, and the circle completes. But it’s not just that the planes are treated as art. They are, thanks to some truly terrific sound design by Koji Kasamatsu, imbued with their own life. Almost every single sound made by the planes is done by the human mouth. When propellers spin, we hear simple “bupbupbupbupbupbups” instead of the actual sound. When we see them crashing onto the snow, instead of a satisfying thud, we hear a “boosh” and a “nyoooooo” preceding it. Most evocatively, when cranking up the engines during a test flight, the sound is replaced by a choir of human moans that move higher and higher in pitch.

To Miyazaki, these planes carry with them the human soul, because they embody human dreams. Throughout the Retrospective, the second-most common theme that’s popped up throughout his work is the idea of flight being the ultimate symbol of freedom, and not even just planes. It goes from airships, to floating castles, to the water-striding train in Spirited Away, even the submarine in Ponyo. The vehicle is damn near fetishized in his films. They take the characters across impossible lands to complete adventures beyond the human imagination. Prior to The Wind Rises, he explored this the most in Porco Rosso, with its titular porcine fighter pilot making art out of the way he maneuvers through the clouds to escape the atrocities of war in Europe. Now, with Jiro’s story, he hones in on the ones who invent those dreams, and the turmoil that comes through it.

In an interview with the Japanese Animation Monthly magazine, Miyazaki said: “I like vehicles and want to continue drawing them, but I have resolved not to draw them in a fashion that further feeds an infatuation with power. In the same way, I think that being infatuated with the world’s biggest battleship guns merely reveals an infantile mentality, and such an infatuation is truly useless in conflicts with more sophisticated nations, who think of war as merely a means to victory, cannons merely as tools to destroy targets.

“I thus have absolutely no desire to follow the course many others take of continuing their infantile infatuation with power, becoming mecha fanatics, and finally becoming knee-jerk advocates of increasing Japan’s military strength. The way I see things, in the world of cartoon films, vehicles should run over the ground, dive into the water, and fly through the air in order to liberate humanity from the things that hold us back.”

With this comes interesting wrinkles, most notable of which is the film’s stance on the Japanese military, not just during that period, but in general. Most of Miyazaki’s more conflict-heavy works tend to have a nuanced yet still very clearly anti-war bent to them, particularly his fantasy adventures Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Princess Mononoke. Meanwhile, The Wind Rises, which concerns itself with a real war, doesn’t spend much time on the atrocities of Japan’s involvement in WWII. That isn’t to say it’s entirely absent from the film, but whereas Miyazaki still took stances towards a particular side in even his most nuanced and morally gray works, he refuses even the tiniest sliver of an easy answer in The Wind Rises.

Thus, the film has provoked controversy, not just from the Japanese media but Western circles as well. Critic Inkoo Kang said that “Miyazaki’s film is wholly symptomatic of Japan’s postwar attitude toward its history, which is an acknowledgement of the terribleness of war and a willful refusal to acknowledge its country’s role in that terribleness.” On the other end of the same spectrum are more reductionist interpretations, like that of Devin Faraci, who wrote “Miyazaki’s latest is about a man who builds killing machines and only wishes they were prettier.”

While it is true that the characters of Miyazaki’s film are all detached from the horrors of war that surround them, this is as far from a morally irresponsible film as you can get. In fact, it is because it chooses to imply the consequences of Jiro’s dreaming more than outright showing them that this becomes not only Miyazaki’s most nuanced and mature film, but also the hardest to digest. Had the film come up with easy moralism and finger-wagging, The Wind Rises would’ve lost the humanity that makes it such a powerful, dense, existentially complicated film.

Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street garnered similar controversy last year, and they’re actually not that different from each other in that department. Wolf was criticized for glossing over the consequences and victims of Jordan Belfort’s heinous actions, just as Miyazaki caught flack for not giving enough screen time to the war of the film’s period. Critic circles mostly defended Scorsese from the rest of the media, while Miyazaki’s controversy received less media attention, yet was more divisive among critics. This is a strange contradiction, considering both films use their deliberate diverting of attention away from such matters in a similar way: to immerse us in the psychology of their main characters. Of course Jiro Horikoshi is distancing himself from the lives that his creations will harm, just as Jordan Belfort is in no way concerned with the people he scams.

This line of thinking culminates in the ultimate question that Jiro’s vision of Italian engineer Giovanni Batista Caproni asks him when his dreams are starting to come to fruition: “Would you rather live in a world with pyramids? Or without them?”

The metaphor is as poetic as it is obvious: we think of the Egyptian pyramids today as one of the most remarkable monuments of human accomplishment and architecture, yet we also tend to ignore the fact that to bring them to life required the slavery and suffering of countless Egyptian workers who were all at the mercy of a ruthless Pharaoh, acting as an unforgiving auteur. The exact inverse is what eventually happens to Jiro’s planes. Today, we see creations like the Mitsubishi A6M Zero (a.k.a. the Zero Fighter) as a harbinger of war and destruction, ignoring both the technical and artistic achievements that led to its creation.

Meanwhile, Jiro proceeds through the film caught in a pyramid-mentality. So starry-eyed and optimistic is he about bringing his designs to life, that he continually ignores the repercussions they would eventually lead toward. This is best exemplified in an early scene in which Jiro finds a photo showcasing that Caproni was successful in creating a massive plane that could carry dozens of passengers. Immediately after, Miyazaki cuts to the painful reality: after the photo was taken, the plane’s wings broke off and the plane plopped back onto the water it had only just lifted off from, after going a few hundred feet. Not once does Jiro acknowledge that Caproni may have failed. He’s too busy looking at the clouds to see that it’s actually smoke from a fire that will eventually be of his own making.

Bringing this film full circle with the retrospective’s very first article is the Japanese voice casting of Hideaki Anno as Jiro Horikoshi. Anno is not a professional voice actor, but a director of animation just like Miyazaki, who worked with him as a background animator for Nausicaä, and is responsible for directing seminal works such as television’s Neon Genesis Evangelion and its subsequent cinematic reboot Evangelion. This casting adds something of an intentionally meta element to the film’s themes. Anno himself is a victim of fulfilling an artistic vision at the expense of one’s own well-being, suffering from the internal consequences of vision rather than Jiro’s external ones. Anno doesn’t really need to “play” the part of Jiro, because he’s already lived it, in a sense.

Upon creating Neon Genesis Evangelion, Anno suffered through clinical depression and budget cuts, incorporating his own psychological problems into the show and its characters as a means of both retaining his original vision and allowing himself a kind of self-therapy. It’s interesting how Miyazaki uses Anno’s persona, considering his previous comments in the Animation Monthly quote regarding the infantile fanaticism of “mechas” — a genre of anime that Anno himself revitalized. That is because Anno didn’t treat mechas as a militaristic ideal of power, but as a psychological prison that bound man with machine, and childhood with adulthood.

When fans were outraged at Anno for taking a less conventional, more abstract route for the show’s final two episodes, Anno subsequently lashed out at all of them, making the even more impenetrable The End of Evangelion, poking fun at the commercialization of his own artistic product, and trolling fans and their theories of what the show is actually about by calling it all “meaningless.” Evangelion is the inverse of Jiro’s relationship with his planes. Whereas Jiro’s artistic achievements bring him happiness at the expense of everyone else’s well-being, Anno’s work brought everyone else happiness at the expense his own well being.

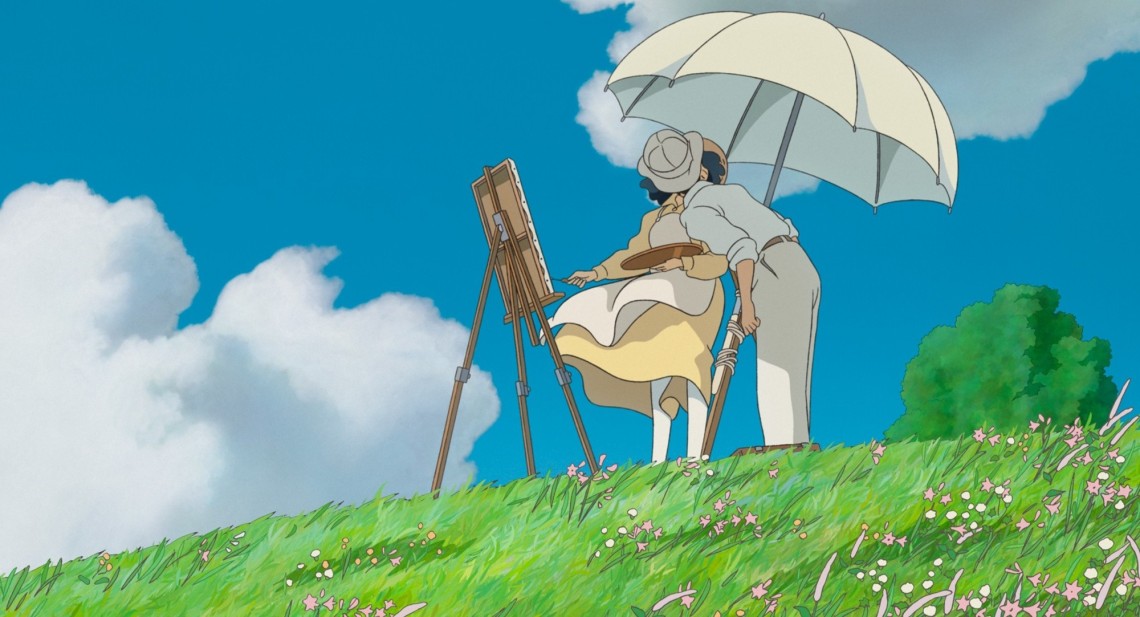

Jiro’s conflict between creator and creation becomes externalized in the form of his romantic partner Naoko, a woman diagnosed with tuberculosis whom he happens to fall in love with at a very inopportune time in both their lives. She could choose to prolong her life by staying at a sanatorium, or she could stay with Jiro while he finishes his design, only speeding up the disease. After staying in the sanatorium for a while, she decides she’d rather live a shorter yet more fulfilled life with Jiro beside her … only to realize what she’s done by the film’s end, sneaking back to the sanatorium while Jiro’s away premiering his new design.

Naoko is a much more traditional female character than the distinctly feminist ones from the rest of Miyazaki’s filmography. She’s simply an object of infatuation here, which is disappointing when compared to the way he’s handled women in the past. But still, in its own way, it’s necessary when given the parallels she raises with Jiro’s dream. She still gets to be more than just an object in this film: she fully represents the purity of Jiro’s dream, throwing her more in line with Jessica Chastain in The Tree of Life than someone like Kiki or San. And even so, she still gets her own moment of empowerment in the end, when she decides for herself to prolong her life, risking her romance with Jiro in the process.

Her parallel with Jiro’s artistic dreams, which is just as poetic and obvious as the pyramid metaphor, is part of what really elevates The Wind Rises for me, as she brings the achingly human element that the fighter planes and Jiro’s cold, detached persona couldn’t provide. If anything, she is the sole human center that provides consequence for Jiro’s insistent striving for artistic purpose. How much is Jiro willing to keep holding onto his dream, even if it runs the risk of withering away. How much is he willing to stay with Naoko, if she runs the risk of withering away quicker just by staying with him.

Furthermore, why must any of this matter when death will inevitably take Jiro’s dreams and lovers away anyway? For no matter what Jiro accomplishes, no matter the pretenses of whether a work of art can “immortalize” its creator, no matter whether Naoko stays with him longer or not, all will disintegrate into dust later on, and be blown away by the wind. Thus, we find ourselves back again at Miyazaki’s most prevalent theme: nature. But not the same kind of nature that provoked Princess Mononoke‘s or Nausicaä‘s environmentalism. Rather, human nature. The Wind Rises suddenly reveals itself to be not just a drama about love, romance, aircraft, or war, but a drama of the very essence of humanity: why do we try to live?

The film’s title comes from the Paul Valéry poem The Graveyard by the Sea. The most common English translation of the line is typically “The wind is rising! … We must try to live!” But in some translations, the word “try” is replaced with “We must strive to live!” And in The Wind Rises everyone does nothing but strive to do just that, because perhaps one can not truly live without struggling and suffering along the way. Yes, Jiro knows that there is a risk to fulfilling his goals, but he moves through them anyway not just because of his vision, but because his vision is tied with an intrinsic desire to truly live. For it is either that or wasting away for the rest of his life, like a victim of tuberculosis — wrapped in a cocoon of blankets, unable to stay with her loved ones. But now that Jiro’s truly lived, he’s finally seen the true cost of what it entails.

I’ve seen The Wind Rises three times in the theater, and with each viewing, I’m more and more convinced that it might outrank Spirited Away as Miyazaki’s greatest accomplishment. It’s not just a towering achievement of the animated medium, but the kind of classically composed drama that Golden Age Hollywood would’ve attempted in live action, only even richer in substance here. Joe Hisaishi contributes one of his best scores, both the Japanese and English dubs are exceptionally directed (special mention to Emily Blunt’s heartbreaking vocal work as Naoko in the English version), and the visuals are as beautiful and unshakeable as you’d come to expect from the director.

I find myself weeping whenever the final scene starts, accompanied by Hisaiashi’s breathtaking violins and the imagery of burning skies and the ruins of Jiro’s planes piling up, the chickens coming home to roost. Because just as much as a drama, character study, and romance, The Wind Rises is also a deceptively-made horror film. It’s a film of such astounding beauty that you let its disquieting darkness slip underneath your skin. It’s something of a downer for Miyazaki to end his career on, but perhaps it’s the most fitting one because of it.

Miyazaki is obviously no Jiro. He isn’t responsible for the deaths of thousands, hasn’t lost a loved one to tuberculosis, and (thankfully) hasn’t succumbed to compromise for the sake of keeping his art alive. The closest thing he’s had to personal turmoil directly related to his art is the brief feud with his son Goro during the making of Tales From Earthsea, and even that was resolved by the time Hayao’s film was well into production. And yet, it’s the perfect summation of his career. Because Miyazaki, an old man with years of experience in the industry, has seen what happens when the wind rises. He’s strived to live and succeeded. And he’s tired from it all. So tired that he’s attempted to retire for years and keeps getting drawn back in, either for professional or even personal reasons. Those that live may never rest. Maybe Miyazaki will recant again and turn out to direct something else in a few years. For now though, let’s let the wind carry his words to some unknown place, and let his work be immortalized in the joy of millions of fans the same that Jiro’s planes have in the slaughter of thousands. Because no matter the difference between their art, both men shall return to the same dust, carried by the same wind.

That concludes the Studio Ghibli Retrospective, but there are still more Ghibli films from more directors to be made, as well as more filmmaker retrospectives to be had. Until then, however, we still have these great films from the past to catch up on.

Previous Editions:

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Previous Movie Mezzanine Filmmaker Retrospectives:

The Darren Aronofsky Retrospective

The Terrence Malick Retrospective

6 thoughts on “The Studio Ghibli Retrospective: “The Wind Rises””

Hey Chris, congratulations on finishing this ambitious project! This final review was immensely pleasurable to read and occasionally brought a tear to my eye as I relive my own experiences with the film. This is truly a great film that I am sure with time will become more and more appreciated. And yes, I do agree that this is probably Miyazaki’s greatest film (to date, let’s hope).

Something I wanted to discuss though was your interpretation of Naoko’s intentions for leaving Jiro. You seem to believe that her decision to return to the sanitorium was one of self-preservation. However, I respectfully think you are mistaken in that the housemaid (I cannot remember her name) intentionally tells Kayo (Jiro’s younger sister) to not try and stop Naoko from leaving or warn Jiro before she is gone, stating “she [Naoko] wants him [Jiro] to always remember her as she was.” To me it seems like Naoko’s decision is all about wanting to leave a happier parting image with Jiro than would otherwise come to be if she died with him. Indeed, Kayo had earlier stated that Naoko’s condition was far worse than she made it out to be indicating that she probably was only a few weeks away from death.

So what do you think now about this scene? Is your interpretation still the same?

Anyway, once again thanks for your efforts Chris and all the best for the future. These Retrospectives are something to look back over with great pride.

Pingback: Watch The Wind Rises (2014) Online PutLocker Free | PutLocker.Pro

Pingback: My Homepage

Pingback: Click here

Pingback: Melissa Williams

Pingback: Java Variable Scope