Claire Denis is a woman of few words, so I shall use that as an excuse to introduce this retrospective briefly. Though I have seen all of Denis’ features now, it feels to me that we barely know each other, that the more we learn, the more we know we do not know of each other, that if we were to see each other at a bar I would not say hello for fear of sounding a fool. She is the type of person with whom you sit by a campfire, and feel as if you must tell her everything you know, but you know that she already knows it all.

Chocolat

The debut of Denis is insidiously tranquil, in that she lets the stillness of each scene say all that needs to be said; a technique that would echo throughout everything her fingers touched thereafter. Tensions dissipate like anger into a wrung towel, just as the destructive nature of her characters seemingly reach their precipice. Claire Denis finds her serenity in the moments where a mad world filled with mad characters are constrained like ships in a bottle, seductively still. She leaves only the anxious strain of its tensely stoic silence to remain, whispering, “But pull up a chair, let me tell you everything.”

Racial boundaries are the chief reason for emotions being wordlessly left to stew within as opposed to blurted out without thought. Even as Luc — the caustic white male with nothing but a fiery trail of chaos left behind over his shoulder — joins the fray and attempts once and for all to rattle and jolt the house to such a degree that no safety hold should be left standing tries, he fails. Things here are pegged down under invisible lines in the same way the horizon is. Protée and Aimée dance around these lines as if they could be walked through at any time; he’s a strange silent fellow who is maybe an immortal philanthropist or maybe just an exhausted hub of frustration and she’s the young and bored and beautiful housewife with the atypical big brown eyes that have seen some shit.

With the inexorable silence beating out its human foes, the sun becomes the biggest star of the picture, filling in for their perpetual inward irritation with the loud buzz of ubiquitous light that can be felt even in the distanceless dark of pitch-black night. A character says, “This house is the last house on earth,” and it is ostensibly the single most truthful line of the film: the horizon gives nothing in the way of tangible existence and it appears the only way to find new friends is have them crash their planes in the nearby mountains. Even the house itself is barren of anything remotely individual and interesting — the whole scene could be easily traded with a generic cliche house used for nuclear testing without a single government official even noticing. Everything is stuck into position, a notion only proliferated by the endless sunlight. Yet everyone fidgets, humans are almost universally fidgeters, and it gets them into such boundless trouble. Little is resolved in an unresolvable situation, people walk into the darkness after burning their skin and others stare into space, decades later they stand in the rain and laugh.

Grade: B+

No Fear, No Die

Dah sits alone in “this car” at night and is illuminated only by his intermittent angsty puffs of smoke, he recites volubly a quote by Chester Himes which dictates that every man of every colour is “capable of everything or just anything” in a flat internalized Bressonian voiceover which pretty much says itself how the next ninety minutes are going to go down. Dah and his partner Jocelyn are in the business of cockfighting, and baby, business ain’t never been much of anything in this dingy underworld. Chasing the blood-soaked violence-ridden American dream is only for the white in the world that Denis sees, but this invaluable business team make a swing of it anyway.

Denis walks to the beat of her drum, and the white oppression of these not-exactly-well-to-do black fellows is present almost instantaneously. Her voice is anticipated and perhaps fatigued, but strong. The cocks battle each other like they know god damn well they’re heated metaphors and the misery and desperation are made ever-increasingly present by the claustrophobic low ceilings and short corridors its inhabitants are confined to. Grimey and sullen, there’s little beauty in this film of pernicious social barriers, but as stone-faced as Dah remains, he doesn’t seem to be one to give in to mental prostration just yet. Ambivalence towards the surrounding destruction as opposed to just plain old self-destruction is still a highly ranked killer, and one might say Dah is pushed further into the inexorably-persistent camp as opposed to wallowing in hopelessness. It’s a difficult drumbeat to continue walking alongside. Denis knows this all too well.

Grade: B

I Can’t Sleep

It begins with two unknown helicopter pilots erupting with contagious laughter for seemingly no reason, as they do nothing in particular. Things here are just simply happening, next to each other, coalescing with all the other moments and people and parallel lines, moving forward because there’s not much else to do. They can’t sleep, why not move. Never knowing that there are sleepless devils that walk among them in plain sight, that there are unimaginable layers under every line. The radio host says, “Follow my advice and remain happy,” which, as far as typical Denis foreshadowing goes, pretty much says that it’s gonna be a rough one.

Yekaterina Golubeva is the stone-faced lamb who’s lost in translation, sporting raggedy clothes and a general 24/7 look of apathy, her 10/10 aesthetics making up for her general facial aloofness in pretty much every aspect of her day-to-day life. And we too are lost with her, we see all the layers of people accidentally looping around each others headrests but we’re not entirely certain why, or who has what to lose, if anything at all. There’s just a thing about a dead body laying amidst recently dropped groceries in a rarely-visited apartment and the lurching feeling that one of these people might meet a similar end.

Haneke’s 71 Fragments immediately comes to mind as a film that also observes monotonous and seemingly unconnected lives all being met with a terrifying end, but the major difference being 71 Fragments assures its daunting end as it opens, as opposed to I Can’t Sleep, which barely lets on the fact there might be a climax. Both troupes of characters move languidly across their respective boards, but here the only protruding thought patterns of the audience circulate just how the potential downfall might come to pass (Denis’s much adored unbridled white oppression enveloping all its inmates in a mushroom cloud of unjust social barriers?), which makes the film somewhat intrinsically anti-climactic because a monstrous showdown isn’t even the business of Denis.

But when Golubeva is told, “You’re young and beautiful, you can do anything,” I’m sure there were more than a few audience members anticipating a piano dropping on her as soon as she next left the apartment. The reveal still manages to be anus-clenching, which stuck with me the longest — I was so into the rhythm of watching this film, I’d all but forgotten about the looming big bad wolf, let alone thought about suspecting one of those already on screen. Shaking the rhythm of Denis is no easy task, it clings to skin and brainwaves with such ferocity that one is inclined to forget they’re even sat down.

Grade: B

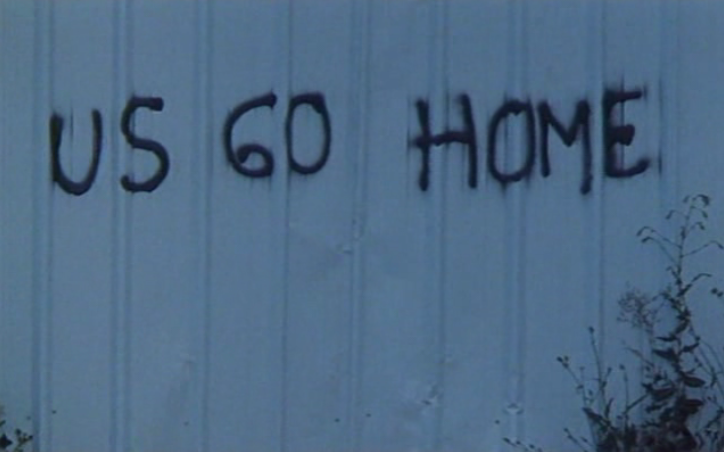

US Go Home

In which Denis portrays a version of Paris that parallels America with all its acoustic freedom, endless sunshine, and sprouting out of pubescence like a naked man in a cake. Of course, these things aren’t exclusive to America and American influence [citation needed], but “Californication” is nevertheless still lapped up as the finest crash-course on learning how to be cool. Animation through music and movies and television is purportedly for the best because they teach us how to be hip, how to dress and smoke and fuck and live. They are the archetypes to “fitting in,” since to not fit in is to be generally lonesome and miserable and blue. And here they are all called Alain.

Maybe it’s the fault of the US and its inexorable westernization, or maybe it’s the opposite of fault. Alain dancing vigorously to “Hey Gyp” whilst periodically puffing smoke is pretty much what cinema is here for, and its magnetism is not far separated from the rest of the film. The whole thing is so damn hypnotic that restarting it immediately after finishing it was a serious option. Things move so effortlessly it’s difficult to imagine it as a made-for-TV production. And then there’s Vincent Gallo who’s cool in that real cunty sort of a way that he is, and he travels with Martine looking for adolescence and another bottle of coke, but the woods are only really there when the headlights are on ’em. Then they go to the bus stop and they wait for it. Everyone has cool messy hair and ill-fitting clothes and heaven forbid they don’t have a pack of cigs and a lighter on hand for damsels in distress. And it’s groovy man, fuckin’ groovy.

Grade: A+

Nenette et Boni

It’s a ghostly world, where the only money made comes from selling phone cards and faulty lighting equipment made in Taiwan. Boni shoots pellets at the neighborhood cats that sit on his lawn, and Nénette’s got that typical teenage apathy toward responsibilities that gets them into trouble in all the ways they expected it to. The two collide in ways only brother and sister know how to — both Grégoire Colin and Alice Houri have played the vicious sibling rivalry out before in US Go Homen — and their toxicity towards each other doesn’t paint a nice symphony for the surrounding neighbors. He speaks in curious monologues to himself and is about 3 points off being admitted, and she wants out, of something.

Their chemistry shakes the foundations, and eventually their collusion becomes mystifyingly endearing, despite their ever-changing character objectives. Boni’s wide brown eyes move from conveying psychotic thought patterns to some serious yearning for love and acceptance. More fascinating yet is how the change comes so effortlessly and yet is still so unforeseen. And then there’s these not-misplaced music videos of Gallo and Tedeschi staring at each other to things like “God Only Knows,” which tie everything together and don’t do anything at the same time. Denis is good at that, at having these things just happen and somehow adding congruence through volatility. She’s zen. “She’s killer zen.”

Grade: B

Beau Travail

Wistful murmurs fall out of Galoup’s withered lips like leaves falling from a tree in heavy wind, while sequences from his time with the Legionnaires play out in his memory. “I’m rusty, eaten away by acid.” His waning spirit has succumbed to a stale and dry end via the potency of old age contemplation, after a traumatic time spent leading troops in Africa towards no certain goals or targets outside of “character-building” antagonism and “an ideal that keeps changing.” Half the time energetic and half the time languidly burdensome, this is a hard film to pin down long enough to make sure its pockets aren’t full of lethal objects; people worship the sun and gentle waves appease the little burns on their naked bodies, dramatic music accosts the sandy apocalyptic landscape of Africa, and big booty beats settle in the darkness.

Denis has the pulse and tempo down by now, and it’s Lavant’s turn to mystifyingly dance whilst puffing smoke — he’s a little more coordinated at dancing his feelings into fruition, and dances like at any moment a bullet might smash into his cranium. The man can DANCE. And sometimes people look into the camera, and that’s just something that people do. And the obstacle courses get easier once you know where you’re going and know how to climb the walls. This is the rhythm of the night, after all, and such rhythms tend to not be so easily traced by graphs and pie charts.