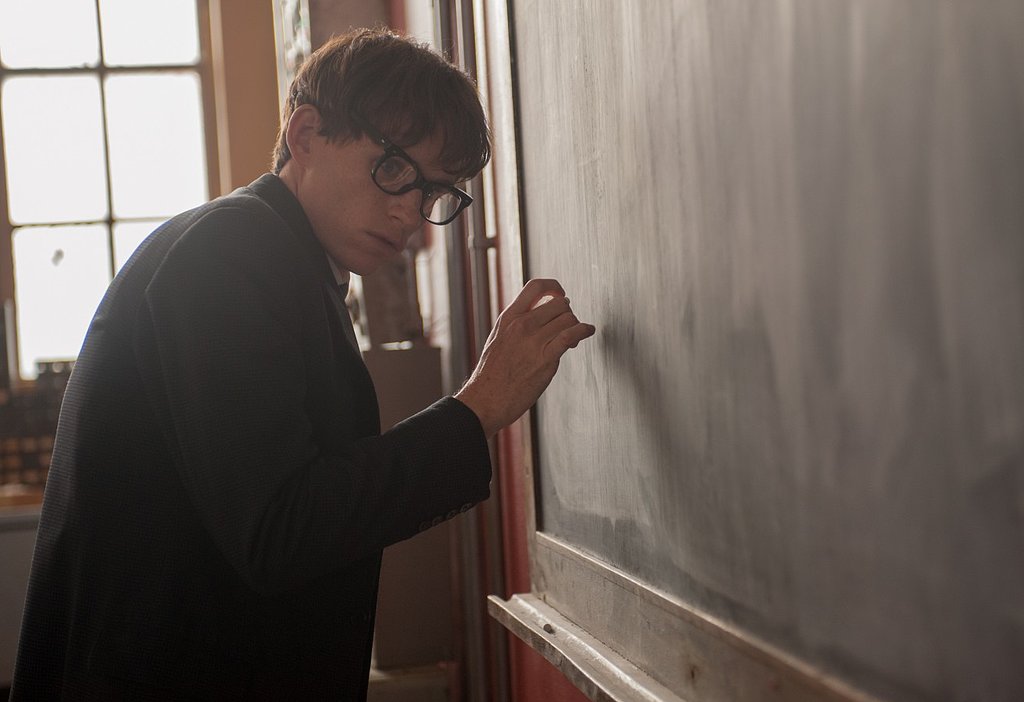

It’s the year of “Oscar’s metamorphosis,” Jenelle Riley beamed in the header of a recent Variety survey of the lead performances anchoring the season’s graduating class of prestige pictures. Reese Witherspoon, she noted, shed her sunshiny demeanour to play a recovering heroin addict in Wild, while other actors went to further bodily extremes: Jake Gyllenhaal doffed 30 pounds to play an unblinking sociopath in Nightcrawler, while Steve Carell donned a prosthetic nose for Foxcatcher. Best of all, Riley suggests, Eddie Redmayne transformed himself “before our eyes” as a progressively degenerating Stephen Hawking in James Marsh’s The Theory of Everything. What greater transformation could there be for an actor in his prime, the reasoning goes, than to follow luminaries like Daniel Day-Lewis into the foreign territory of the disabled body?

Actors’ chameleonic efforts to reject the defining biological and social cards they’ve been dealt is widely celebrated to the point of being fetishized outside of prestige season, to be sure. You could think of Leos Carax’s Holy Motors, for example, as a mildly satirical essay about precisely this fixation, on how actors become other people while more or less staying within the confines of their own bodies. But there is a tendency to crank the hype dial on the perfectly fine work of handsome performers like Redmayne that is particular to this year-end moment—a habit of treating as inherently laudatory an able-bodied actor’s bodily contortions in service of a supposedly authentic rendering of a disabled subject. Put another way, the de facto celebration of Redmayne’s project owes less to his arduous task of inhabiting an idiosyncratic genius like Hawking—the suffering savant being another type well-served by the Oscars—and more to his ostensible daring in trespassing through a body that is so visibly not his own, the better for us to marvel without shame at Hawking’s physical transformation while celebrating the performer’s.

Though Redmayne’s Oscar-bound disability-tourism is going according to script, SAG nomination in hand, The Theory of Everything is not without mild surprises as far as its representation of disability goes. The film lands just shy of the right balance of respect and prurience in its treatment of Hawking’s transition from layabout Cambridge graduate student and croquet-playing boyfriend (to Felicity Jones’ Jane, later the first Mrs. Hawking) to ALS patient and troubled genius, a world-renowned cosmologist who can’t quite put his fork through the broccoli on his plate. Though Stephen and Jane’s courtship under the shadow of illness plays out like a Muppet Babies variation on A Beautiful Mind’s portrait of John and Alicia Nash— complete with outdoor banquets and stargazing—Marsh is not inattentive to the more quotidian side of Hawking’s disability.

On the one hand the filmmaker’s totemic representation of Hawking’s procession of wheelchairs, from manual to electric, owes something to the X-Men prequels’ po-faced depiction of Professor Xavier’s wheelchair as his defining physical object, as well as a true skin for him to settle into as he effectively grows into the man he will become. Yet Marsh also allows Hawking’s assistive devices—including, eventually, the computer through which he speaks— the rare privilege of being functional at times rather than always symbolic of the stages in the life of a butterfly emerging from its cocoon. For Marsh that means casually taking stock of the navigational process by which a disabled person, even a famous one like Hawking, traverses both accessible and inaccessible spaces in the course of his personal and professional lives. This is conveyed through steady medium shots of the hero being hauled up and down stairs, with or without his chair, coming out of elevators, going down ramps, and so on.

For all the talk of his physical transformation, Redmayne, too, is rather more low-key than the hype might suggest, and sensitive to crafting a holistic profile of his subject rather than conjuring a conventional image of a beautiful mind trapped in an increasingly gnarled body. His delicate work across phases of Hawking’s life stands out against both the awards season rhetoric of shapeshifting and the film’s own wearyingly deterministic structure. Consider the opening credits, which see Hawking segueing into an impromptu bicycle race through the city with fellow Cambridge man Brian (Harry Lloyd) after a match dissolve links the tires on the elder Hawking’s wheelchair with the spokes on his younger self’s bicycle. That suggests an origin story marching inexorably from health and youth to disability and aging, which is more or less supported by the obnoxious late-film conceit of rolling back time to Hawking’s (and the film’s) salad days.

But the text’s dunderheaded insistence on charting the simultaneous evolution of a mind and devolution of a body isn’t reflected in Redmayne’s performance, which never quite settles into the mannered compilation of tics and bad posture that would seem to be invited by Marsh’s preference for medium close-ups of the actor’s emotive face. Indeed, Redmayne translates the young Hawking’s penchant for wolfish grins and imperious head-cocking gestures from his unblemished state to his later years as a disabled man and pop science figurehead. He diffuses even the most potentially pathetic set piece, Hawking’s discovery of a grand theory while turtled under a knit sweater he can’t quite poke his head through, with a haughty laugh. As demure as the film is about the couple’s sex life—it’s only tackled circuitously, through Hawking’s friendly admission of the “automatic” processes he is more than capable of, and a sly cut from a moment of mild intimacy to a new bouncing baby—there is something ineffably randy about Redmayne’s bearing, a trace of good breeding, privilege, and sexual confidence that well exceeds the narrative trajectory of the film, from blushing boy to disabled guru.

Why, then, the fixation on Redmayne’s physical transformation at the expense of his consistency in crafting a character—which is often manifest as a physical consistency at that? Perhaps because it is a winning formula, not just for actors in search of hardware but also for the craftspeople that support them. Speaking to The Hollywood Reporter last month, costume designer Steven Noble and hair, makeup and prosthetic designer Jan Sewell pressed more or less the same buttons, pitching Redmayne’s appearance in different phases of the film as a Gregor Samsa-styled metamorphosis. For Hawking’s later phases, Sewell observed, she had a head shape made “so you got the visual effect that the face was starting to slope.” A designer like Sewell speaks of transformation, you might guess, because it is the most visible trait in a largely invisible profession.

Or perhaps this rhetoric persists because on the whole we have not yet found a way to speak of disability as a social phenomenon and a particular lived experience, given to the mundane far more often than the tragic, rather than as a sorry physiological state for us to gawk at safely and sympathetically, through the distancing medium of film acting. Films like The Theoryof Everything are not in the same league as P.T. Barnum’s circus, and Redmayne is not a sideshow performer like, say, Frank Lentini, the Three-Legged Football Player. But there is a sense in which freak-show culture is reborn in a more toothless and perhaps more insidious manner every time one of these performances becomes the next Oscar sure thing, a chance for Eddie Redmayne to stand on the stage of the Kodak Theatre and speak, as, pundits will inevitably note, while Hawking himself cannot.

One thought on “The Prestige Freak Show: Eddie Redmayne’s Metamorphosis in “The Theory of Everything””

Pingback: Thumbnails 12/18/14 – Movie Categories.com