As we’ve already established, Goro Miyazaki’s Tales From Earthsea was Studio Ghibli’s first disaster. Despite making lots of money at the Japanese box office, it also had the much more affecting consequence of being their first critically reviled film. Having hired a director, the son of their flagship director Hayao Miyazaki, with no directing experience whatsoever to adapt one of the most beloved yet dense fantasy novel series was certainly a contributing factor, but it also had the added bonus of Goro simply not having a knack for traditional storytelling, how it works, or how to properly pace it. It did prove one thing, however: that Goro was a talented director of animation and visuals, crafting stunning vistas and beautifully fluid animation (though it certainly helped to have a talented team of animators working alongside him).

It was because of this that the announcement of Goro’s next film, From Up On Poppy Hill seemed like the perfect counterweight to the Earthsea fiasco. Instead of creating a large, sprawling fantasy akin to Miyazaki’s more epic works, the film was based on a 1980 manga of the same name, and featured a much simpler story that took place in 1963 Yokohama, right before the ’64 Olympics would take over the city; thus falling more in line with the more realism-based work of Isao Takahata (Grave of the Fireflies, Only Yesterday) than of his father. Speaking of which, Hayao Miyazaki — after having a tumultuous relationship with his son during Earthsea‘s production — finally decided to acknowledge his son’s talents by contributing to the screenplay, co-writing it with Keiko Niwa (who also co-wrote Earthsea with Goro).

With Goro’s visuals, Hayao’s storytelling, Takahata’s inspiration, and much more manageable source material to draw from, it seemed like Goro would finally make a genuinely good movie and an undeniable improvement over his last film. That latter fact is most definitely true (though it’s not hard to improve after a film as bad as Earthsea), but in terms of being “genuinely good”, it barely makes it there.

The film begins with a very poetic conceit for a period coming-of-age drama: we open with the morning ritual of 16-year-old high school student Umi, who begins each day by waking up early to make breakfast for her entire family, and then raise a set of flags in her backyard. These “signal flags” carry with them a hidden message that only sailors know how to translate, saying “I pray for safe voyages”. She raises them each day in the hopes of reconnecting with her father, who disappeared on duty in the Korean War and has been presumed dead ever since. This ritual ends up getting the attention of a classmate, who writes a poem about “the girl who raises the flags” in the school paper.

It is through this story of lost and found connections in a postwar environment that Goro lovingly recreates ’60s small-town Japan. His environments are packed with small details and motion in the very corners of his frame, and the film as a whole perfectly captures the tone of sweet nostalgia of times gone by. It’s a good thing that it nails the tone and visuals so well, because it’s otherwise the only thing From Up On Poppy Hill has going for it.

While the main storyline of Umi falling in love with the boy who wrote the poem, Shun, and her desire to discover an inkling of a connection with her father is still intact, the film meanders through two subplots: one having nothing to do with the overarching story, the other adding unnecessary, soap-opera hysterics to an otherwise grounded film.

The first involves Shun’s Anti-Demolition League, which is trying to protest the destruction of the school’s old Latin-Quarter clubhouse in the wake of Olympics construction. Umi becomes caught up in Shun’s juvenile activism, creating posters, attending debate rallies, and getting the entire female student body to help clean up the clubhouse.

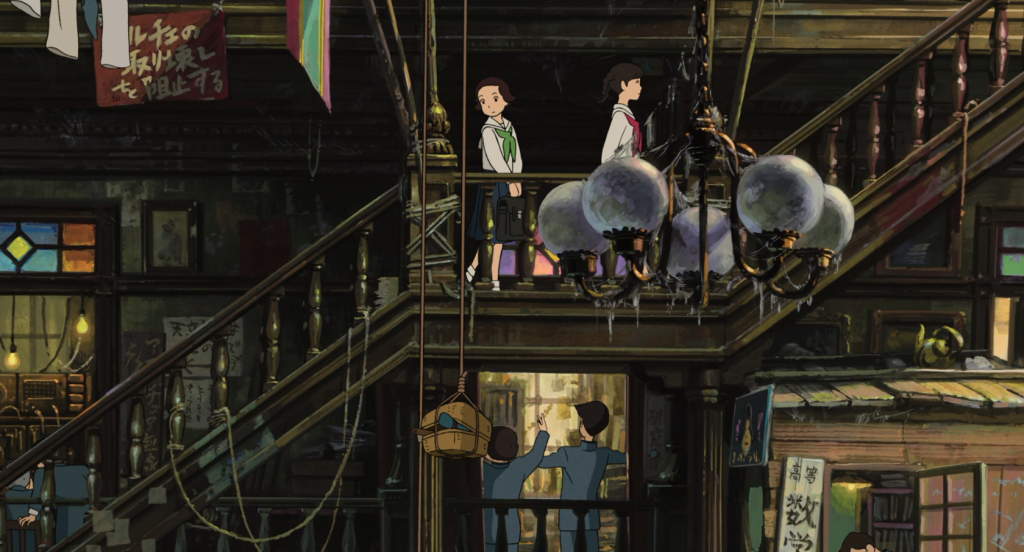

The clubhouse itself is a remarkably drawn structure, reminiscent of places like Howl’s Moving Castle and Spirited Away‘s haunted bathhouse, with stairways looping around old chandeliers and each floor housing different clubs and personalities. Its visual design is also one of the only notable qualities of this particular subplot, whose only purpose in the narrative is for characters to pronounce the themes of the film in passionate speeches. “We can not forget the past or we’ll lose sight of the future!” they all shout to the audience, with little variety in between. Otherwise, it’s just visually appealing filler that stretches the film to an already short 90 minutes.

The other subplot, which actually has something to do with the larger story at hand but also happens to hamper the film, is the revelation that Shun and Umi may in fact be long lost siblings, thus holding off their budding romance. “This is like some bad melodrama,” Umi points out upon hearing this shocking information. Rarely does a film acknowledging its own contrivances work out in its favor, and From Up On Poppy Hill doesn’t even come close to transcending that rule.

Both subplots are resolved in just the ways you’d expect by the film’s end, but not in a particularly remarkable or satisfying manner. This could be just as much a fault in the source material as it is in the writing and execution, but it’s still rather hard to believe how clumsily and forcefully the film is written.

But really, these are all secondary faults to the film. What From Up On Poppy Hill truly lacks are characters. Umi and Shun are blank slates, wholly unremarkable, and without a shred of personality to them. They go through their routines, blandly react to each other’s romantic longings for one another, and speak to each other with broad pronouncements and language instead of small, personable nuance.

Even the way they’re animated is bland. Goro has decided to go for an excessively minimalist approach with his depiction of the character’s movements in and around Yokohama, especially when compared to the subtle yet impactful gestures found in Only Yesterday or Whisper of the Heart. But Goro commits to that minimalism to a fault. Not only do these characters talk without personality, they haven’t been lovingly rendered or drawn like the environments have so clearly been. Each of these characters could be anyone, and thus, they are no one.

So really, this is still a rather mediocre film. Much better than Earthsea ever was, but exceedingly far from the quality of even lone masterworks like Yoshifumi Kondô’s Whisper of the Heart. And yet, even with all of this film’s faults, I still find myself oddly swept up in its familial drama, as Umi makes do with what little connection she has with the father she’s barely ever known. And the unfortunate part about that is that it has less to do with the actual film’s effectiveness and more to do with its behind-the-scenes implications.

When you watch a Goro Miyazaki film, it is practically impossible to view it without comparison to his father’s films and career. He lives in a perpetual shadow and sadly still hasn’t found a proper voice to really break out from it. But with From Up On Poppy Hill, he shows some clear signs of artistic discovery, with an approach that feels fully unique to him — the excessive minimalism — even if it isn’t wholly successful. But it also proves strangely moving how he depicts Umi’s invisible connection with her absent father figure, drawing noticeable parallels to how he views his own newfound career as the son of Japanese animation’s most legendary figure, and how lost and disorienting such a Herculean position is.

Tales From Earthsea opened with the protagonist murdering his own father, possessed by a supernatural hatred that he couldn’t control. From Up On Poppy Hill opens with the father figure already an apparition, and ends with not much changed. Even though Umi will never be able to reunite with her dad, she can still discover new ways to connect with him beyond the corporeal, such as Shun’s personal relationship with him, bound also by only memories and little more.

This becomes even more resonant when you see how Goro and Hayao actually got to work together for the first time with their collaboration in this film, able to establish the physical connection that Umi and Shun will never have with the man they both miss, as well as the artistic, spiritual connection that will continue to last. This doesn’t make From Up On Poppy Hill an objectively better film, but it shows that while Goro still has a long way to go, he will continue to search for and strengthen that artistic connection only further. No matter the film’s faults, there’s still something deeply felt in here that allows it to transcend.

Regardless, the film was generally well received by audiences and critics alike, becoming yet another high-grosser in Japan, a moderate success in Europe and the US, and a much more critically praised film from both Japanese and Western critics. But just as Goro Miyazaki gets to have a moment of real success for himself, his father Hayao takes over the spotlight yet again with his latest, most daring, and personal work yet. Next time, the Studio Ghibli Retrospective finally comes to a close with Miyazaki’s masterful, historical drama The Wind Rises.

Previous Editions:

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Previous Movie Mezzanine Filmmaker Retrospectives:

The Darren Aronofsky Retrospective

The Terrence Malick Retrospective

One thought on “The Studio Ghibli Retrospective: “From Up On Poppy Hill””

I actually like the “slice of life” approach in this movie. 2 main themes that I really remembered from this film is the way Umi longing for his father and the bright, hopeful spirit when looking into the 1964 Olympics.

Though I like the tone of the film, “Although we are brother and sister, I still love you” dialogue is very medicore, even with the animation standard (and come to think of it, that’s for me one of the weakness of Hayao, how he portraits young love story (Whispers of the Heart having a boy want to get married with the girl, the love of 2 main characters in Princess Mononoke, even the love in Spirited Away); sometimes I think it would be much more effective if they are just friends; it’s their relationship that counts…