Throughout this retrospective, I’ve talked at length about Miyazaki’s visual and thematic fascination with flight. But I haven’t talked as much of another somewhat consistent image in the famed animators’ work: castles. We certainly have obvious choices like the titular fortress of Castle in the Sky, the one from Miyazaki’s feature debut before forming the Studio, The Castle of Cagliostro, and the one that occupies this week’s film; but we also have more unconventional versions of this trope of sorts, like the Bathhouse in Spirited Away, and the pilots’ resort found in Porco Rosso.

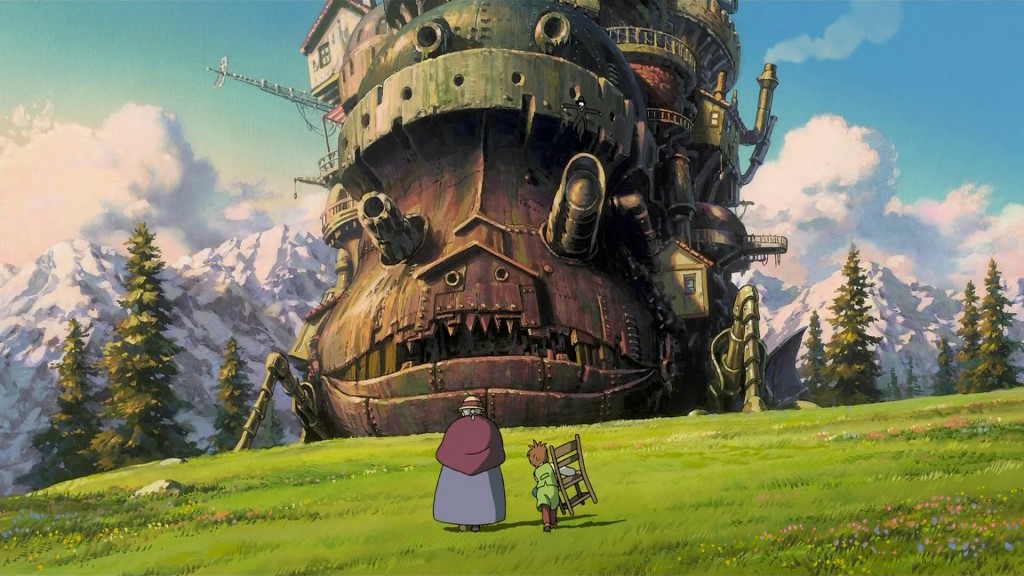

Miyazaki has a real knack of establishing a sense of place and majesty in even the simplest of places–like the bakery in Kiki’s Delivery Service–, but it’s his castles and fortresses that manage to be the most memorable. There, he languishes on filling these architectural wonders with such an astounding, almost unnecessary level of detail, and we can see the animator having some of his most fun establishing and imagining these mighty monuments. In a way, these castles are just as much characters as the humans, and the one in Howl’s Moving Castle is such an incredible creation that it almost threatens to overtake the film, in a sense. But then again, that’s kinda the point.

We open in a fantasy/steampunk setting somewhat similar to the one in Castle in the Sky, where flying machines, giant moving castles that walk on mechanical legs, and large airships occupy the same space as witches, wizards, and demons. Our protagonist Sophie is an unassuming woman who owns “a tacky hat shop” in a small market village by the river. A war is going on all around her between kingdoms, but her concerns are more simple and personal; she simply doesn’t have the time nor the energy to be caught up in patriotism like her neighbors are.

One day, she’s almost sexually harassed by a duo of soldiers (despite the double entendres–this being a family film–, it’s still rather obvious what they’re really after), when a handsome blonde wizard named Howl rescues her and returns her safely to her hat shop, thus getting the attention of the Witch of the Wastes. Jealous of the young, beautiful Sophie winning Howl’s attention, who she’s planned for years to literally steal his heart, the Witch curses Sophie with a spell that transforms her into a frail, 90-year-old woman. Determined to break the curse, Sophie journeys to the Wastes to find her, and instead comes across the Moving Castle of the title, where she meets the Castle’s odd residents — a young boy practicing magic named Markl and a fire demon who powers the castle named Calcifer — as well as its owner who, coincidentally, happens to be Howl.

As you may have noticed from the above synopsis, there’s a lot going on in the plot of the film, forgoing the simplicity of something Totoro, yet having a different kind of focus than his other plot-packed film Princess Mononoke. This is part of what’s made Howl’s Moving Castle the director’s most divisive work in his filmography, at least in the anime fandom: there are those who condemn it for how much of a mess the actual plot is (it’s famously the only Miyazaki film that Roger Ebert gave a somewhat negative review) and then there are those who still rather enjoy it in spite of its writing issues.

Part of that has to do with the source material Miyazaki and co. are adapting this time around. Whereas before, they’ve worked in an exclusively Japanese mindset–adapting either mangas, Japanese young-adult literature, or repurposing cultural folklore tales–Howl’s Moving Castle was their first attempt at adapting Western material: specifically, a British fantasy novel by author Diana Wynne Jones. Whereas the mangas, young-adult novels, and folk tales they worked with were punchier and shorter, fitting their animated style more easily, Jones’s novel was a fairly sprawling and detailed work with a lot of subplots and fantasy tropes all mingling together. Any adaptation of this material would’ve been hard to pull off, animated or otherwise, so the fact that Miyazaki’s film is actually somewhat (though not entirely) coherent is something of an accomplishment.

Most of the story’s problems come in juggling all of the many subplots while attempting to keep its focus on one. Whereas Princess Mononoke managed to circumvent this problem by giving equal focus to each of the factions of its war between forest gods and human settlements, Howl’s Moving Castle takes place in the backdrop of war, but hardly ever brings nuance to either factions’ actions and motivations. This is because the focus is primarily on the characters’ personal concerns and relationships, which don’t always involve the war or a huge understanding of it. Sure, there’s talk of a missing Prince that’s been causing this conflict and other such matters, but that’s given second fiddle compared to the relationship between Sophie and Howl, and how they break free from their respective curses.

And really, despite the muddy narrative regarding its fantasy war, stolen hearts, witches and wizards, etc., it’s the more intimate character relationships that ultimately make Howl’s Moving Castle work as a whole. The entire cast is likable, with the dual Sophies filling the roles of both the plucky heroine and the gentle mother figure at once, and adorable side characters give the entire film a surplus of personality, like the aforementioned Markl and Calcifer, a dog named Heen that wheezes whenever it tries to bark and flies with its ears, and the scarecrow Turniphead with his everlasting cheshire grin.

Then there’s Howl, who’s self-absorbed, flamboyant, and undoubtedly flawed (in the novel, he’s also a womanizer, which is a detail that’s thankfully not explored in Miyazaki’s adaptation), but still remains good-natured in his own right, and you can tell that he genuinely cares about protecting his strange, makeshift family at the castle. When they’re all together, the film really gives off the warm vibe of a family being formed out of drastic circumstances, simply yet another example of Miyazaki’s effortless conjuring of charm and optimism against a backdrop of very dark and sometimes sinister subject matter.

It also helps that the film has one of the Studio’s best English dubs, with none other than Christian Bale voicing Howl, Emily Mortimer and Jean Simmons as the young and old versions of Sophie, a young, pre-Terabithia Josh Hutcherson as Markl, and a lively Billy Crystal as Calcifer that rivals his turn as Mike in the Monsters Inc. movies (not coincidentally, the dub was managed by PIXAR’s own Pete Doctor, who directed Monsters Inc. and Up). Each of the actors feel perfectly cast–complete with Bale using his gravelly Batman voice in a menacing nightmare scene–and do these strange characters justice.

Really, though, it’s the relationship between Sophie and Howl that mostly carries the film. Similar to Princess Mononoke‘s San and Ashitaka, Sophie and Howl are both outcasts with a similar dichotomy: one is an outcast by nature, as Howl willingly purged himself of his own heart to save and bind himself to Calcifer, which in turn stunted his emotional development yet also gave him unlimited power as a wizard; while Sophie is an outcast by circumstance, her own fears of being mediocre and ugly brought to life by the Witch’s curse, and literally forming her new identity.

Their relationship brought to mind Beauty and the Beast, but with both parties having their own “beast curse” to break–Sophie’s obviously being her old woman form, while Howl’s is a literal crow beast that allows him to fight against the forces threatening his loved ones, but also make it harder to turn back into a human with each transformation. Kinda ironic how Howl’s moments of humanity are what force him to forsake his human form. Like San and Ashitaka, they’re two halves of a whole, Sophie’s fears of mediocrity plus her emotional maturity ultimately completing Howl’s boundless magical power and adolescent emotional development.

This all ties back to Howl’s Moving Castle; that magnificent, strange creation. Like many of Miyazaki’s most memorable locations, Howl’s castle is representative of something, albeit more specific than the pure wonder of the Castle in the Sky or the industrialized workforce commentary of Spirited Away‘s bathhouse. Instead, the Moving Castle is less a personification of a mere concept or theme and more of a literal, physical epithet for each of the characters to hide in.

In a way, part of what makes this story irksome to certain people is how it mostly consists of our characters running away from their problems rather than confronting them head on. Specifically Howl, who is, in some ways, the most cowardly of the family. When summoned by the King to fight in the war, he convinces Sophie to pretend to be his mother and explain to the King that Howl is too much of a baby to go fighting. Seriously.

Instead, Howl would rather sulk in his Castle, which is a near-literal emotional prison. Each of the characters find themselves trapped there in some way by their own insecurities and fears, as the Castle simply wanders the land like a Nomad with no place. The Castle itself is magnificently designed and animated, but mostly because of how Miyazaki and his animators have committed to making it really, really ugly. Walking on giant iron chicken legs, it’s less of a Castle and more of an inhabitable robotic turkey, as houses on top of houses are bunched together with constantly billowing chimneys, the Castle wheezes and coughs out smoke, moaning with concerted effort for each and every step it takes, and the turrets form a toothy, goblin-like grin. It’s as hideous as each of the characters’ faults, and still it soldiers on in beautiful scenery.

Eventually, the Castle is utterly destroyed by the film’s end, as Sophie, Howl, and the others quickly learn not to leave behind their flaws but instead make peace with them. The epilogue features their ugly Moving Castle rebuilt, but now with wings that let it soar the heavens. Of course Miyazaki would end a story like this with their freedom being symbolized by flight. Whereas his other films were about innocence, war, or nature, Howl’s Moving Castle is about maturity, which one can argue has always been a Miyazaki theme considering his coming-of-age tendencies, except we never really see that same innocence found in Spirited Away, Kiki, or Totoro, at least in the same way. In fact, this is more of a story about adulthood than anything else, which makes for a rather interesting progression in his thematic journey.

No, Howl’s Moving Castle doesn’t have the subtlety or complexity of Miyazaki’s other works. It’s less quiet and contemplative, and thus is given less room to breathe like his other masterpieces, making its almost relentless spectacle feel more hollow than usual. But all of his other good qualities remain in tact: a wonderful female heroine, sympathetic villains, likable characters, boundless visual imagination, lovely humanism, and one of composer Joe Hisaiashi’s most memorable themes.

It was also yet another huge box office success for the Studio, making $235 million worldwide, and also having the strongest North American gross in the company’s history thanks to its star-studded English dub, proving that the Studio’s big gamble with adapting such a dense piece of Western fiction more or less paid off. But it wasn’t until afterwards that the Studio made an even bigger gamble. Next time on the Retrospective, we chronicle the directorial debut of Hayao’s son, Gorō Miyazaki, which is the only film in the Studio’s history to receive a largely negative critical consensus: Tales from Earthsea.

Previous Editions:

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Previous Movie Mezzanine Filmmaker Retrospectives:

The Darren Aronofsky Retrospective

The Terrence Malick Retrospective

3 thoughts on “The Studio Ghibli Retrospective: “Howl’s Moving Castle””

Pingback: Howl’s Moving Castle | That Critic Chick

Miyazaki’s fascination for castles possibly stems from The Shepherdess and the Chimneysweep, Paul Grimault’s animation that would later evolve to become The King and the Mockingbird.

Both he and Taratata mention it as a huge influence, the latter going as far as telling it defined his carreer choice. The design of the eponymous Castle of Cagliostro was inspired by that movie. Miyazaki stated it inspired his use of verticality.

I realize I’m six years late, but this is the best commentary I’ve read concerning HMC.