The end of the year is, undoubtedly, a time of reflection: what we’ve experienced, what we’ve learned, how many resolutions we broke and what we’re going to do to rectify that, etc. It is also the time of lists. Lists, lists, lists. The internet in mid to late December is like the Wonka Factory, but with lists, and the Oompa Loompas fighting amongst themselves as to thinks what candy is best. At the behest of critic Kevin B. Lee, the usual end of the year rankings were supplemented by end of the half-decade list making. The online film community began scrambling to compile their best and favorite films that were release from 2010 to 2014. Some see list making as arbitrary and dumb, but Jake Pitre and I are of the opinion that there is some value in the process. Not only does it reveal personal proclivities, but it gives the opportunity to champion under seen and overlooked gems. When considering five years’ worth of cinema, Jake and I took it upon ourselves to make a list not of the best, or even necessarily our favorites, but of films that you should consider including before laminating and subsequently handing over to Isabella Rossellini as a feeble method of flirtation. (Unfortunately, Blue Velvet – woo woo – was ineligible due to its 1986 release date.) Without further ado, films you shouldn’t forget about when making your best of the half-decade list.

Spring Breakers (2013) | Directed by Harmony Korine

“Act like you’re in a movie or something.”

Every so often, I think about the frat boys who saw the trailer for Spring Breakers and marked the release date on their calendars. I love these frat boys. Whatever this neon Skrillex party porn thing is, I imagine them thinking, I’ve got to be there. They walk in and they sit down, laughing and talking loudly about how they hope Selena Gomez shows her breasts. Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers begins, Skrillex starts up, beer is being poured over countless tits, and the frat boys are locked in.

But the thing is, Spring Breakers is not the spring break movie they expected. Disney Gone Wild it is not. This is something else entirely, and Korine has played the frat boys – and us – for fools. We let him win. Spring Breakers is what we get, and goddamnit, it’s what we’ve earned. American dream/American nightmare. Exploitation/commentary/affection. Notice me, take my hand.

The subtext. So much of it, and so disparate, that it could all be rendered meaningless. Instead, each time it’s something else. An interrogation of white culture’s mass appropriation of black culture. Deconstruction of class and American capitalism through the lens of religion and sex. A critique of modern sexual politics and the power imbalances therein.

A hack provocateur like Harmony Korine somehow created this masterpiece of aesthetic pleasure, morality, melancholy, culture. And in the end, through the beauty and rage, it is the most terrifying horror film in modern cinema. Everytime I see you in my dreams, I see your face, it’s haunting me. – Jake Pitre

Melancholia (2011) | Directed by Lars von Trier

It’s the end of the world, and Lars von Trier knows it. While Nymph()maniac might be his magnum opus, Melancholia still resonates even more, not because of its depression allegory, but because of the compelling argument he makes regarding death and depression: embrace it. Embrace it in order to control it. The provocation that exists in Melancholia isn’t of the same sort that has existed in von Trier’s previous work; it’s less about genital mutilation, or an entire town taking advantage of Nicole Kidman, and more about the emotional and psychological implications of a character’s actions that are fueled by depression. The provocation lies in allowing the audience to identify with Kirsten Dunst’s Justine, or conversely, with Charlotte Gainsbourg’s Claire. It’s not wrong to identify with either, both of whom experience distress in different ways, yet the societal stigma is so strong (something von Trier sort of addressed in The Idiots) that many feel hesitant to even characterize themselves as mentally ill.

Beyond that important thematic rumination, Melancholia is as visually lustrous as any of von Trier’s late period work (though, perhaps, slightly less Tarkovsky inspired). So much shimmers, from the moon’s glow to Dunst’s radiant skin as she lays pensively by a stream, recalling The Death of Ophelia. Though much of the action is of a more observational quality, every moment is a propellent to the emotionally and viscerally overwhelming ending. If you ever get the chance, see this film in theaters: its ending, which makes the entire theater quake, makes it a truly transcendent experience. – Kyle Turner

Black Swan (2010) | Directed by Darren Aronofsky

To compare a movie to a dream or a nightmare is not at all novel. That said, in Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan, no other analogy could better encapsulate the chaos we witness. Nina’s drive for perfection is also her downward spiral, and nothing is ever quite as it seems. Can we trust anything? Or is it all unreliable, shifting, posturing, manipulating? When I think abstractly about the film now, it feels somehow lesser for a moment. But then I remember the visceral experience of actually watching it, on edge and anxious, in a way that is more unsettling and effective than anything in an IMAX theatre. It’s art-horror, if we want to be pretentious about it. Though how else to describe the harrowing but beautiful destruction on screen, in which an obsession with perfection is rewarded and punished, confirmed and denied? It’s Aronofsky’s simplest film, but also his best. – Pitre

Les Amours Imaginaires (2010) | Directed by Xavier Dolan

The young Québécois director certainly made an assured debut at the age of 18 with I Killed My Mother, but he’s far more lauded for his third and fifth films, Laurence Anyways and Cannes Jury Prize winner Mommy. What gets lost in the mix is arguably the film that is able to achieve most successfully what it sets out to do. A kind of stylistic essay on lust, this is Jules and Jim meets When Harry Met Sally…, by way of Montreal hipsters. Les Amours Imaginaires is much derided for its ostentatious presentation, which seemingly riffs off of everyone, from Almodóvar to Godard to Woody Allen. I hate to be “that guy,” but I feel like the film’s critics don’t get it. To be fair, to be the same age as the threesome in Dolan’s sophomore effort is truly beneficial. Its veneer of superficiality and pretension is exactly the point it wants to make about lust and infatuation. Underneath the polished surface, though, is emotion and vulnerability that is truly raw and real and tender, proving that showing off is only part of the story. – Turner

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) | Directed by Wes Anderson

Wes Anderson’s most Wes Anderson-y movie is pure cinematic bliss. Anderson has always possessed a somewhat sick sense of humor, but this is his darkest and most graphic film, while also being his zaniest. One can imagine Anderson giving the finger to his many haters, inventing his own candy-colored country with impossibly sophisticated production design, while indulging in his aesthetic affectations to a degree never before imagined. But just as the film balances the darkness with the absurd, it rather thinly hides a deep sadness around its edges.

Keenly aware of his polarizing impact, Anderson subtly suggests a kinship between M. Gustave (played by Ralph Fiennes, who for my money deserves the Oscar) and himself. “He certainly sustained the illusion with a marvelous grace,” F. Murray Abraham as the elder Zero intones, and the gravity of that line is palpable for Gustave and Anderson both. Time goes on, things change irrevocably, and in the end it can seem as though none of it matters. “Oh, fuck it,” you might as well do what you can, and look good doing it, trying your damnedest to preserve everything you have built, even if only a lonely girl is eventually left to care. – Pitre

Mildred Pierce (2012) | Directed by Todd Haynes

Mildred Pierce occupies a relatively unique place within the world of auteur-driven television. In fact, one could argue that it is one of the most important developments in made-for-television cinema, as opposed to a more generic made-for-TV movie. Todd Haynes seeps his female protagonist (a truly outstanding Kate Winslet) in her era (the Depression), allowing for his pet subject of identity as a social construct to weave itself in and out naturally. Lovingly photographed in 16mm, there’s a golden hue to the cinematography, and it’s worth noting that so much of the film is shot through windows and reflections. Haynes deftly illustrates that it’s the fact that everyone is watching her that makes Mildred who she is. – Turner

Inside Llewyn Davis (2013) | Directed by Joel & Ethan Coen

Llewyn just can’t catch a break! The longer I have had a chance to sit with this movie, the more I think that it is a serious contender for the Coen brothers’ best film. Llewyn, smothered in the coldly surreal blues and greys and browns of cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel, is our wearily sarcastic but hopelessly desperate guide through this hazy cinematic folk song. Played with a heavy heart by the great Oscar Isaac, the character – and the film – are bleak without being nihilistic (well, mostly), honest without being ham-fisted. So bitter and embattled, Llewyn is a stone-cold folk singer who could maybe succeed if he’d just put his heart on his sleeve (I’m writing a folk song right now!). Inside Llewyn Davis is devastating when it makes you think about how people change and how they don’t, and the consequences of each. Or is the tragedy truly that he’s good enough, but that’s all? – Pitre

Weekend (2011) | Directed by Andrew Haigh

My favorite way to describe the beautiful Weekend goes as follows: What initially begins as a one-night stand between Russell (Tom Cullen) and Glen (Chris New) evolves into an encounter far more intimate than they anticipated. Weekend argues that every moment of intimacy, whether carnal or emotional, is in essence a moment of vulnerability that impacts who we are. It’s the best kind of queer film, one whose specificity lies in the queer experience, but whose themes of love, performance, and validation have a universality about them. There’s almost an incomparable closeness that Ula Pontikoos’ camera is able to capture. Haigh later brought this wonderfully warm tone to television with HBO’s Looking, but it’s in Weekend that he articulates that so much can be said with only a gesture. – Turner

Upstream Color (2013) | Directed by Shane Carruth

How much control do we really have over our own identities, over who we develop relationships with? What brings people together? The power of Shane Carruth’s comeback is that it can be adored on aesthetics alone, with its lush visuals and imagery, and his striking original score. It is an absolutely stunning film to look at and listen to. On top of that, though, the enigmatic puzzle Carruth weaves for us is eerie and confusing, potentially leaving one feeling fairly lost in the abstract. That is, if it wasn’t for the strong emotional grasp of the central romance between Kris (Amy Seimetz, sublime) and Jeff (Carruth), and Carruth’s respect for his audience, trusting us to make connections and absorb his ambitious logic and flow and not count on exposition, explanation or really much talking at all. Simply breathtaking in its uniqueness, expressionism and confidence. – Pitre

Frances Ha (2013) | Directed by Noah Baumbach

At first, it’s hard to find much sympathy for the kind of post-grad ennui story that Frances Ha depicts, but wait until you get to know Noah Baumbach and Greta Gerwig’s spritely protagonist. She’s adrift but refuses to acknowledge it, adolescent but “old” (she’s 27, and 27 is old), and her relationship with her best friend is evolving at a rate she finds overwhelming. It would be too easy for the film to attack or mock Frances, perhaps a criticism lobbed at Baumbach in the past for his caustic portrayals of “unlikable” personalities, but Gerwig (also co-writer on the film) brings so much warmth and pathos to the character. She has an undeniable magnetism that isn’t rooted in mockery. Funny, melancholy, energetic, endlessly quotable (“I’ll pay you $200 to get no cats”), and shot in shimmering black and white, getting to know and love Frances is, shall we say, wonderfully modern. – Turner

The Wind Rises (2013) | Directed by Hayao Miyazaki

Hayao Miyazaki’s films are often so lovely to spend time with because they lack outright antagonists and their narratives flow a little aimlessly, rather than progress sensibly. Some see this as a bug, but it is certainly a feature of his filmmaking. The Wind Rises is such a powerful way for him to say goodbye because his main character, warplane engineer Jiro Horikoshi, is its antagonist. Contrary to the reports of some, the real struggle of the film and of Jiro is the bittersweet realization that everything beautiful also dies, and can be used for ill. He dreams of his gorgeous mechanical inventions, but is punished by having to behold their destructive use. We create art, only to have it be cursed, with nightmarish decay overpowering beauty and craft, dreams be damned. Is it better to have loved and lost than to have never loved at all? – Pitre

Coriolanus (2010) | Directed by Ralph Fiennes

Not unlike The Hurt Locker meets Shakespeare. The Bard is always relevant, but his more obscure play about male ego in the midst of war seemed especially prescient and ripe for an updating. Ralph Fiennes’ capable direction juxtaposes the archaic dialogue against the brutality and elusiveness of battle. It’s both so beautiful and horrendous. – Turner

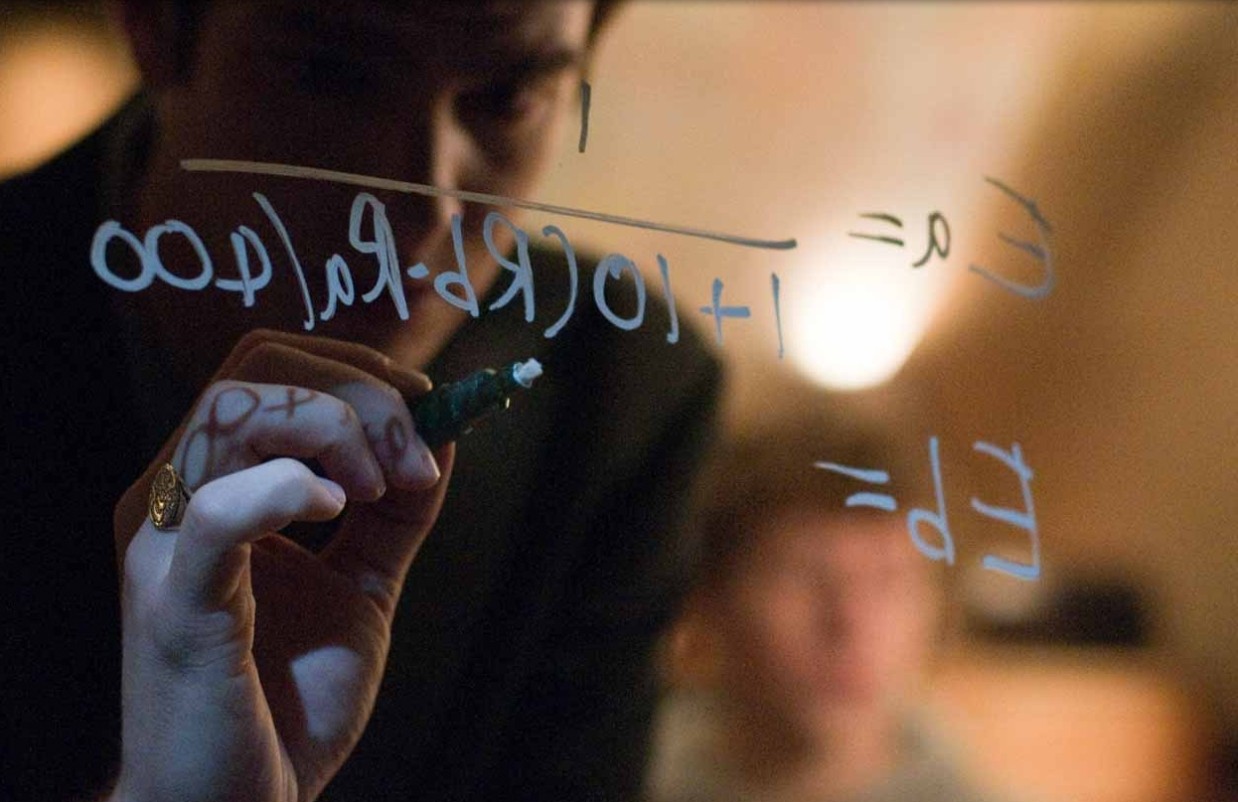

The Social Network (2010) | Directed by David Fincher

You sit down at your laptop and open Facebook. You have a crush on this girl from class that you spoke to once, and you used that as an excuse to add her on Facebook, so you go to her profile. Hmm, you think. You like her profile picture. You wait. Minutes later, she likes your profile picture. The question then becomes, who will message the other first?

What is Facebook for? There’s a compelling argument to be made that it exists to facilitate new ways to flirt, to connect, to love. The root of it all, it is said, is a somewhat pathetic attempt to prove something, to impress a girl, to get her back, to get her attention, to do something. Who are we to argue? Hit refresh. – Pitre

Oslo, August 31st (2012) | Directed by Joachim Trier

Joachim Trier’s masterwork paces itself like a stroll – there’s a particular place it’s going to get to, but each step is more hesitant than the next. Less about drug addiction than a feeling of alienation, despite a desire to assimilate into normalcy, Oslo, August 31st remains one of the most beautifully haunting films I’ve ever seen. – Turner

The Tree of Life (2011) | Directed by Terrence Malick

What to say that hasn’t been said to death already? The ultimate expression of “it’s not a movie, it’s an experience,” the real beauty of Malick’s film is that you can’t separate the transcendental magnificence from the student art film pretentiousness, and the invigorating fact that there is no point in making a distinction. His vision is so assured that the confidence overcomes any misgivings one may have about the abstraction. I’m not religious, but this film is undeniably a divine piece of work, so very human and yet somewhere beyond. – Pitre

Poetry (2011) | Directed by Lee Chang-dong

Some films are just elegant and poetic enough to warrant being referred to as an elegy, and it’s with specific intention that such a film as Lee Chang-dong’s Poetry should recall that term. Yoo Jeong-hee lives as an older woman who, while struggling to take care of her slovenly and irresponsible grandson, as well as battling Alzheimer’s, begins to experiment with manifesting her complicated feelings in the form of poetry. Lee’s films are emotionally draining, but they are so invested in their characters and in enveloping the audience in their world. It’s with a careful brush that Lee paints, making every frame and word, as in poetry, matter. – Turner

Holy Motors (2012) | Directed by Leos Carax

Leos Carax might be an asshole, but his Holy Motors is so important for its zaniness and its melancholy, and the impossible relationship between them that it so capably walks. As a bitter eulogy for the death of film, Carax’s acidic tendencies can take away from his message. Denis Lavant’s incredible performance takes care of that, instead proving the medium’s distinct power and the grand possibilities of acting. By anticipating the end, we get evolution. – Pitre

Young Adult (2012) | Directed by Jason Reitman

Young Adult is the perfect piece of evidence in support of Rebecca Mead’s excellent New Yorker piece on likable characters. Mavis Beacon is not likeable, nor is she supposed to be. And yet, with Diablo Cody’s sharp writing and Charlize Theron’s ferociously controlled performance, she’s worthy of our interest and sympathy, in spite of her self-destructive and narcissistic behavior. Do we ever really grow up? Cody suggests maybe not. – Turner

Tomboy (2011) | Directed by Céline Sciamma

I saw Sciamma’s deeply affecting film recently, and I was struck by the way it explores gender so strongly by doing so within the already-tricky confines of adolescence. Laure is new in town, and after the local kids see her as a boy, she keeps it up as she nurses a crush on Lisa. There is much to be said about the success of the film on a social level, considering the ambiguity and complexity of gender and the cruelty of gender norms, but it’s also intimate and tender in its nuanced portrayal of Laure/Mikäel by the remarkable Zoé Héran. – Pitre

Before Midnight (2013) | Directed by Richard Linklater

While the rest of you may fawn over Linklater’s latest film Boyhood, it’s Before Midnight, the most recent film in his Before series (preceded by Before Sunrise and Before Sunset), which most intimately examines the passage of time and how that impacts our lives, our views, and our loves. – Turner

So, how did we do? Are there any other films we should remember whilst making our lists? Let us know in the comments!

8 thoughts on “To Half and Half Not: The Films to Remember from 2010 – 2014”

It doesn’t make sense to me that the best film of 2014, as ranked by Movie Mezzanine, is Under the Skin, but the movie from 2014 that gets mentioned is The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Disregard my previous comment, I just read the prelude! (Sorry)

Damn fine choices and write-ups. A lot of those would show up on my list.

Most of these would end up on my list as well, but I would have to include ‘Drive’ and ‘Blue is the Warmest Color’.

Some hidden/overlooked gems for me:

Bal (Honey) – Kaplanoğlu

The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceasescu – Ujica

Chico & Rita – Errando/Mariscal/Trueba

This Is Not a Film – Jafar Panahi

Pariah – Dee Rees

Tabu – Miguel Gomes

No – Pablo Larrain

Like Someone in Love – Abbas Kiarostami

The Past – Asghar Farhadi

Pingback: Video Essay: Kevin B. Lee's The Best Films of the Decade So Far | Movie Mezzanine

Anyone else find those paragraphs on Spring Breakers a bit pretentious?

A few more films that will likely make my decade-end list: Take Shelter, Looper, Her.