The Movie Mezzanine Filmmaker Retrospective series takes on an entire body of work–be it director’s, screenwriter’s, or otherwise–and analyzes each portion of the filmography. By the final post of a retrospective, there will be a better understanding of the filmmaker in question, the central themes that connect his/her works, and what they each represent within the larger context of his/her career. This time, we delve into the strange world of David Lynch’s mind, attempting to make sense of things along the way.

—

For many who only know David Lynch for Twin Peaks and his more surreal film work, The Straight Story is simply considered “that one Disney/G-rated Lynch movie”. A shock to many at the time of its announcement, many considered it strange that a director known for making lurid, bizarre, and often disturbing films would make something as tame as a G-rated Disney film (halfway false considering the film was independently produced and Disney merely acted as distributor after its successful Cannes debut). It almost turned into a punchline. A Lynch movie without depravity, nightmarish imagery, and shocking scenes? How deliciously absurd, am I right?

Even Lynch himself found The Straight Story to be totally distinct from his previous works. It’s the only film of his in which he gave no contribution to writing the screenplay (which was written by John E. Roach and Lynch’s frequent collaborator Mary Sweeney, who also produced and edited this film and many other Lynch works), and Lynch shot the film in an interesting manner: every single scene was filmed in chronological order, and on-location in the actual route that Alvin Straight took, whose 300-mile journey on a lawn mower was the true story that served as the basis for the film. Richard Farnsworth, who plays Straight, even agreed to shoot the film in spite of suffering from prostate cancer. When we see him struggling to stand back up on his two canes, we are seeing Farnsworth in pain, and that passion managed to pay off with an Oscar nomination for his role. Lynch said in an interview with Empire that it was actually his “most experimental film” (Granted, that interview was conducted before the making of Inland Empire).

On paper, it’s odd seeing Lynch tackle such wildly different material by his standards, but when you really think about it, a lot of Lynch’s films tend to deviate and experiment in some new way, and a G-rated road trip film was yet another evolution of that. Moreover, when you finally see the film, you realize that for all its superficial differences from the rest of his filmography, this is still a David Lynch film: An external journey that also constitutes as a subconscious odyssey. Into where? The past, the future, the secrets and sins of this old man whose lived it all, and much more.

Today, our David Lynch Retrospective slows to Sunday Drive speed as we take a look at a film that’s both acclaimed and yet somehow also underappreciated, like an old neighbor down the street whose been all but forgotten in the passage of time. This is The Straight Story…

“The worst part of being old is rememberin’ when you was young.”

Though this is technically not a Lynch script, you could see and feel Lynch’s influence over it, with surreal characters and strange lines of dialogue coming and going throughout Alvin Straight’s journey, as well as an odd atmosphere that permeates the entire production. You could see why Lynch was drawn to the material and would direct this script.

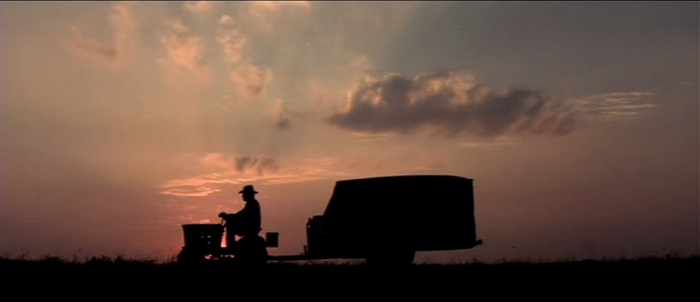

The film introduces us to Alvin Straight’s midwestern world with a quiet mood and careful, methodical pacing. An old man in his late 70s, he lives in Laurens, Iowa with only his mentally challenged daughter Rose (a quietly heartbreaking Sissy Spacek) to keep him company. Upon learning that his distant brother Lyle (Harry Dean Stanton) has recently suffered from a severe stroke, Alvin finally decides to reconnect with his brother before age gets the better of the both of them. Unable to drive, and completely set on taking the journey on his own, he sets up a riding lawnmower with a trailer full of gasoline, water, and braunschweiger weiners and sets out to journey all the way to Mount Zion, Wisconsin entirely on his own.

The Straight Story is simply a damn fine movie, but its damn fine for reasons that the traditional viewer may never even see or notice. The late Roger Ebert likened the film to an Ernest Hemingway story (the plot certainly has shades of The Old Man and the Sea), and I couldn’t think of a more apt comparison. It’s simplistic on the surface, yet contains an uncommon depth, using its basic structure to wring out themes as far reaching as guilt, loss, mortality, and redemption.

This is Lynch conquering slightly more crowd-pleasing, inspirational storytelling in a manner that I find much more satisfying than the abundance of sap that distanced me from The Elephant Man. It’s a slow-moving film, but it contains a palpable friendliness and sincerity that draws you into its slow pace. It’s like wading down a river staring at a sunset. Or, more fittingly, like lying on a distant field and simply staring with wonder at the stars.

Richard Farnsworth is brilliant in it (the film gave him his second Oscar nomination), as is Sissy Spacek and the rest of the small supporting players that Farnsworth interacts with over the course of his journey. Seeing Farnsworth’s weary yet soulful face for the entire hour and fifty minutes of the film simply ties the whole thing together.

I mention this because this is one of the only times a cast ends up being the star player(s) of a Lynch film. Usually, you watch a David Lynch film to experience his unique brand of nightmarish insanity, and as much as I love his indulgent descents into the surreal, it’s nice to see him scale back and tell a story with delicate restraint and aplomb. The Straight Story demonstrates that he has more range beyond scaring or weirding-out the pants from audiences, and craft something that’s simply delicate and assured.

Stylistically and structurally, it’s just as filled with surreal asides and idiosyncrasies as his other films, albeit in more subtle ways. This technically being a road-trip film, Alvin encounters many strange characters in his travels, sometimes for seemingly no reason. An entire horde of marathon bikers pass by him, as does a hitchhiking teenager who later joins him for dinner, and most memorable of all, a crazy woman runs over a deer, only to burst into an angry rant about how this has been the umpteenth deer she’s run over in seven weeks, all before moving back onto the road like it never even happened.

These brief excursions from the main plot also highlight another Lynchian tendency: Bizarre tonal shifts and scene transitions. The aforementioned “deer lady” scene starts off normally, only to rapidly spiral out of control with the sound of her car hitting the deer. We aren’t shown this (what with the G-rating and all), but the camera does perform a jarring snap-zoom square on Alvin Straight’s face reacting to the crash.

And yet, Lynch applies these tendencies to a more heartwarming story. The Straight Story is a much warmer film, and it is precisely this warmness that distracts many people from what really makes it great. In spite of its G rating, that undercurrent of darkness which can always be found in every David Lynch film is still present here, and it evolves as the film progresses. It may be hidden away in the background, and it isn’t quite as depraved as some of the darkness found in Blue Velvet or Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, but it’s there all the same, and it informs all of the events and actions we witness in the film.

This undercurrent is most noticeable when we learn of some genuinely terrifying, traumatizing events from Alvin’s past: his story of the horrible deed he committed when he fought in the trenches of World War II, the reason why Rose can’t be with her children anymore, and most importantly, his history with alcoholism, which contributed to a dispute that tore apart the bond with his brother for an entire decade, all of which reveal that in spite of the friendly, sunny, inspirational overtones of The Straight Story, that underlying menace remains.

It should be noted that this and The Elephant Man were the only films of Lynch’s that I hadn’t seen prior to starting this Retrospective series. It was my first time viewing the film, and while I was taken in by its warmness, I was still very much aware of the more somber thematic undertones that lurked within the film. I thought one viewing was enough to get the movie–somewhat uncharacteristic for a Lynch film, but because I saw it as a more traditional story, I thought that Lynch was holding back on this one. I underestimated The Straight Story.

Upon suffering writer’s block while writing this piece, I did what I normally do when I get writer’s block: complain on Twitter. Thankfully for me, complaining on Twitter proved more useful than I thought when the always handy friend-of-Movie Mezzanine Peter Labuza suggested this little theory: “Write about how it’s basically Blue Velvet except it’s all internal”. I found it interesting. I didn’t fully agree with it at first (and who knows, maybe he was just being sarcastic and I couldn’t catch onto it, because internet), but it was the first thing to get me to reconsider the whole film; suggesting that perhaps The Straight Story wasn’t as “straight” as its title implied.

Embarrassing word-play aside, I did something I rarely ever do and re-watched the film immediately after having already seen it, focusing more on those background elements that I noticed but mildly disregarded. Through this viewing experience, some interesting, and sometimes disturbing parallels were found.

I should’ve expected this, but once again, I underestimated the film, so just sing the words along with me because we should all know the tune by now: The Straight Story works at its most fascinating best when you view it as more of a subconscious odyssey than an external one.

It’s easy to see why Lynch often does this with his narratives. Lynch has always been a supporter of transcendental meditation, and firmly believes that delving into the subconscious is how we better understand our own lives. He incorporates this notion not only in his more explicitly dream-like narratives, but also in his more traditionally told ones. Every part of this journey has to have some kind of meaning to Alvin, and more specifically, it has to lead into his past, which is brought up a lot as one of the main themes of the film.

Some images ended up reinforcing or informing things that the script leaves unexplained. For example, we never get a good, rational explanation for what exactly happened with Alvin’s wife, but one shot I’ve never forgotten since seeing the film, even the first time, is when he gets on a bus that is populated almost entirely by old women his age. As he walks to the backseat, they all start to swoon at him, comparing him to their old or deceased husbands. And yet he walks by them without so much as a hint of interest. I saw this as the stroll of a man whose resisted temptation.

Seeing it a second time, I thought back to Alvin’s history with alcoholism and saw this brief sequence as something that informed that missing gap in Alvin’s past: That perhaps his alcoholism had him sleeping around with other women while he was still married, and ruined his marriage. Now he’s moved past that, and he’s a better man, sitting in the back seat instead of biting the apple, and riding forward on his pilgrimage. Considering this is a journey of redemption and atonement that Alvin is taking, it’s not too far of a cry to suggest.

Many other elements feel like allusions to Alvin’s past. The teenage hitchhiker serves as a reminder of the trials and tribulations of raising a family, allowing Alvin to share his incredibly moving speech on the subject. The “deer lady” feels like a crazed reminder of Alvin’s traumatizing World War II history. He regrets having killed all those soldiers, even though it was all his fault, much like this woman who regrets having run over over ten deer in the past seven weeks, even though that’s clearly something that doesn’t happen entirely on accident. Meanwhile, we witness constant reminders of Alvin’s age and mortality all throughout the film: The young bikers just speeding past his slow lawnmower on the highway, the lawnmower in question constantly breaking and having to be replaced or fixed throughout his journey, and it can’t be a coincidence that Alvin’s final stop before finally reaching his brother’s house is a graveyard.

But to me, the most perplexing part of Alvin’s journey was the surprisingly terrifying moment where his lawnmower speeds out of control when rolling down a hill. Doesn’t sound all too suspenseful on paper, but Lynch films it with queasy camerawork and odd choices of editing and scenery. Namely, at the bottom of said hill is a burning house that firefighters are hosing down while a group of four people sit back and watch on their lawn chairs from a safe distance. The crackling of the flames is intercut with Alvin’s losing control of the lawnmower in a disquieting fashion. It was strange when I saw it the first time, but it wasn’t until the second viewing that I noticed a peculiar connection.

The other time we hear about fire affecting Alvin’s past is when he talks about what happened with his daughter Rose’s kids: Someone else was taking care of her children, a fire spread and severely burned one of them, and because of Rose’s mental deficiency, the state decided that she was unfit to take care of them. It was, and still is, a heartbreaking story. But when you consider the visual storytelling that Lynch is using to imply rather than explain, it becomes even more tragic.

The fire at the bottom of the hill, Alvin’s terror as he’s losing control, his frightened face intercutting with the flames. Lynch is clearly suggesting that there’s a connection between Alvin and the fire that tore apart Rose’s family. We already know that Alvin has a rough history with alcoholism. So it was with all these pieces in place that I started to wonder… was Alvin the one that started the fire? Was this yet another awful sin that he wished to redeem himself for with this “pilgrimage”, cutting himself off from his daughter Rose, the only constant reminder of that wicked accident that ruined both of their lives?

I decided to do something I don’t normally do (which you could say has become a theme for this essay) and decided to surf Google to be sure I wasn’t the only one who was thinking this. Sure enough, there was an old Film Quarterly essay by Tim Kreider published 13 years ago that suggested this very thing.

“But this burning house is not just a surreal non sequitur,” he writes. “It’s one of the central images in the film. This scene functions as a flashback to the earlier fire, the one in which Alvin’s grandchildren were burned. Alvin’s face, bathed in sweat and flickering orange with firelight, and his eyes, bulging and rolling in his head like a frightened animal’s, express a terror that transcends his immediate situation. When intercut with those quick, jarring shots of the blazing house, the real object of that terror is unmistakable. Alvin is the unnamed ‘someone’ who was supposed to be watching Rose’s kids. He let his grandson get burned. He caused his daughter’s children to be taken away by the state. After he manages to stop his tractor, he sits panting and shaking in terror, stating at nothing, the burning house clearly framed in the background. He is trembling not just in reaction to his near-accident, but in an abreaction to that original trauma–another time when Alvin Straight lost control and events took on their own scary, unstoppable momentum.”

Lynch subliminally inserts those deeds in the backgrounds of the frame all throughout The Straight Story. Even if we don’t notice them, like I did in my first viewing, you still feel that palpable darkness that Alvin is trying to fully cleanse himself. When the film opens, we think of him as a kind, unassuming man. But was he really fully cured? He doesn’t drink anymore, sure, and he is living with Rose, but that doesn’t mean that the wounds have been properly healed. They haunt him even as he’s attempting to make amends with only one cord he’s broken: his brother.

It took me a while to realize it, but The Straight Story still manages to operate under Lynch’s thematic obsession with dualities, and of darkness lurking within what is seemingly idyll. We see Alvin Straight at first as a kind, gentle old man, and Lynch continually peels back the layers to reveal and attempt to exorcise his sins, the same way that we would see that white picket fence as the pure American Dream before seeing the ants crawling underneath the surface. Perhaps that’s what Labuza meant when he told me that this was an entirely internal Blue Velvet.

When Alvin Straight finally does make it to his destination, Lynch wisely underplays the reunion between Alvin and his brother Lyle, giving their interaction only a few small lines before fading to credits. “Did you ride that thing all the way out here to see me?” Lyle asks Alvin, who responds only with “I did, Lyle.” It’s the final line of the film.

Was it all enough? Would Lyle have responded differently if Alvin was just dropped off from a bus? According to the imagery that Lynch puts Alvin (and–lest we forget–the audience) through, I’d like to say it was enough, but we’ll never know for sure. All we know is that Alvin Straight went through a pilgrimage of forgiveness and redemption, experiencing and re-experiencing sins and forgivenesses from his past. All in the hopes of a better future. Like all Lynch films, it’s the subconscious journey that justifies and informs the destination, and brings truth to the individual. Even if Lyle doesn’t really forgive Alvin, it will be Alvin who comes out the better man.

So perhaps some of my colleagues were right, in a sense. In spite of the many aspects that differentiate this story from his others, The Straight Story is, in many respects, a distillation of Lynch rather than a departure. In more ways than I could’ve imagined upon first viewing.

Remember when I said that watching this film was like wading down a river at sunset? Well, if that’s the case, Lynch does such a good job of keeping our gaze at the horizon that we only notice that it was the sharks that were guiding the boat until we actually bother to submerge ourselves into the water. Is The Straight Story one of my favorite David Lynch films? Hard to say. Is it one of his most meticulously, and perfectly constructed? Well, I just can’t disagree on that one.

The Straight Story may not have impressed at the box-office (Making less than $7 million of its relatively meager $10 million budget), but it was a darling with critics and audiences. Regardless, in spite of its financial status, it was still deemed something as a “comeback” for Lynch (again, Lost Highway was another one of his misunderstood “failures”), and Lynch was still soldiering on with a return he had always wanted to make: television. ABC, who aired Twin Peaks, greenlit his latest television endeavor: a drama set in the seedy underbelly of the Hollywood industry titled Mulholland Dr. A two-hour pilot was shot, only to be canned later on due to many disputes with the studio regarding suggestive content, length, and other matters.

While Lynch clearly isn’t one to give up on a project so easily, it was still rather apparent that Mulholland Dr. couldn’t continue on in the restricted, heavily censored world of television. So, like what he did with Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, he turned to film, and the result is arguably his greatest film, and definitely his most infamous.

Stay tuned for next week, as we take a crash-course down Mulholland Dr.

Previous Editions:

Previous Movie Mezzanine Filmmaker Retrospectives:

2 thoughts on “The David Lynch Retrospective: ‘The Straight Story’”

I wasn’t a big fan of the film when I first watched it. It wasn’t that it was bad, but it definitely caught me off guard in it’s slow place and relaxed atmosphere. You’re review (like all of them so far) has really given me a new appreciation for the film. Keep up the good work.

Pingback: The David Lynch Retrospective: 'Inland Empire' | Movie Mezzanine