The Movie Mezzanine Filmmaker Retrospective series takes on an entire body of work–be it director’s, screenwriter’s, or otherwise–and analyzes each portion of the filmography. By the final post of a retrospective, there will be a better understanding of the filmmaker in question, the central themes that connect his/her works, and what they each represent within the larger context of his/her career. This time, we delve into the strange world of David Lynch’s mind, attempting to make sense of things along the way.

–

“I’m through with film as a medium,” David Lynch wrote in his book Catching the Big Fish. “For me, film is dead.”

Of course, it should be noted that Lynch was referring not to cinema as a whole but instead the process of shooting movies via celluloid strips, instead advocating the rising prominence of digital cinematography. He lists the pros of digital video’s efficiency: “You have forty-minute takes, automatic focus. They’re lightweight. And you can see what you’ve shot right away. With film you have to go into the lab and you don’t know what you’ve shot until the next day, but with DV, as soon as you’re done, you can put it into the computer and go right to work.”

This efficiency brought Lynch to become more experimental. After Mulholland Dr.‘s rather successful release (complete with an Oscar nomination for Best Director), while fans of the director were anxiously awaiting a follow-up, Lynch instead decided to experiment further with digital video. “I’m shooting in digital video and I love it,” he wrote in that very same book. “I have a Web site and I started doing small experiments for the site with these small cameras, at first thinking they were just like little toys, and they were not very good. But then I started realizing that they’re very, very good — for me, at least.”

Through that website he developed two mini-series –the crudely animated Dumbland, and Rabbits, the surreal “sitcom” about anthropomorphic rabbits that featured the vocal talents of Mulholland Dr.‘s Naomi Watts and Laura Harring– as well as an 8-minute short film called The Darkened Room. But even with Lynch experimenting with new forms of distribution and media, the question that remained on mostly everyone’s minds was when his next real film would come into fruition.

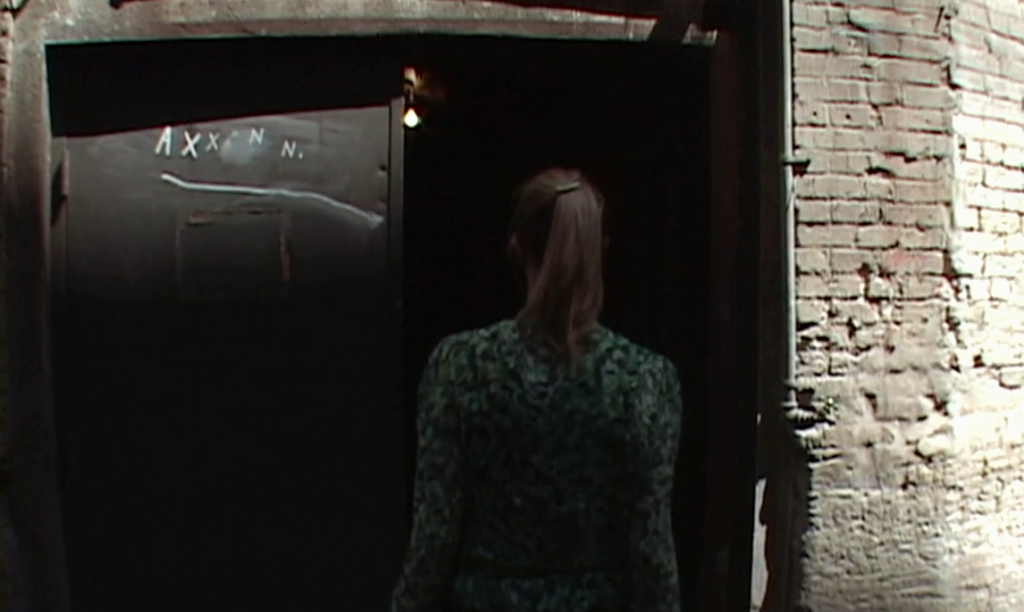

Little did these people know, however, that all of these experiments were, in many ways, the precursors to what what eventually evolve into Lynch’s most bizarre, incomprehensible, difficult, and epic experiment. Our David Lynch Retrospective finally reaches its close, as we dive headfirst into the elusive Inland Empire.

“From Hollywood, California . Where stars make dreams, and dreams make stars.”

Throughout the David Lynch Retrospective, I’ve given out my own personal interpretations and concrete explanations for Lynch’s more dream-like, unconventionally told films. Inland Empire is the exception. Here is a film that defies logic, reality, and traditional cinematic storytelling. Sure, plenty of Lynch’s films contained irregular means of structure, but there was still a structure of some kind to latch onto. Inland Empire, by comparison, is largely a series of loosely connected vignettes whose connections toward each other are never quite clear.

At first, it seems Inland Empire is about an actress named Nikki (Laura Dern) who nails the part of a lifetime in an upcoming film, only to discover that the production is cursed; originally a German film that was never completed after the two leads were murdered. Now Nikki and her co-star Devon (Justin Theroux) are in those very same shoes, with a hapless director (Jeremy Irons) forced to deal with the mounting tension. It’s a rather simple set-up for a good mystery film, but this being a David Lynch film, things get complicated.

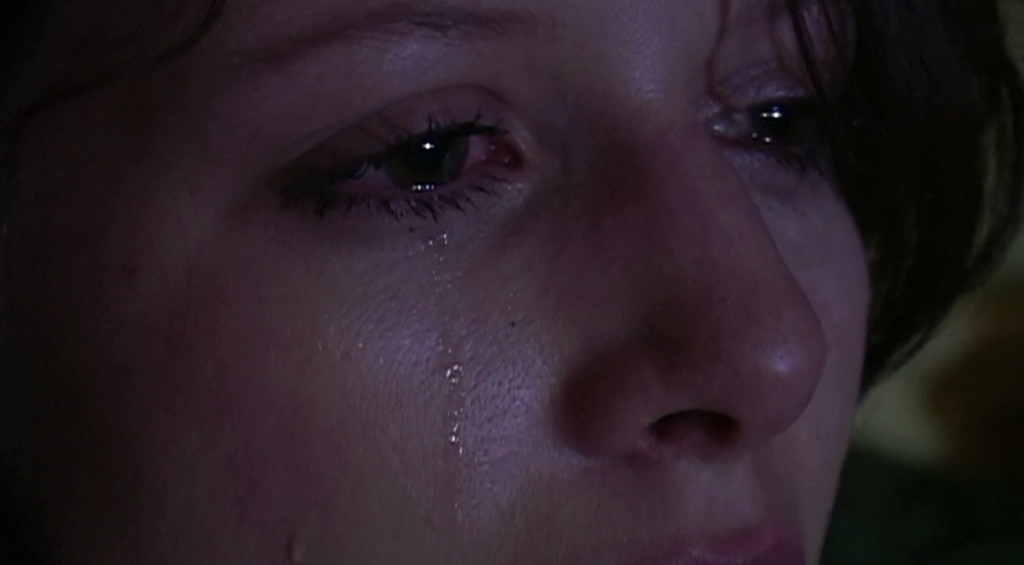

The first symptoms of wrongness come when Nikki and Devon begin to call each other by their character names, Sue and Billy, instead of their real ones. Nikki even has conversations that she thinks are real but are proved otherwise when the director yells “Cut!” from the background. The film continues like this for the first hour, fiction and reality slowly growing more and more indistinguishable from each other, until suddenly, Nikki/Sue finds herself running into a set that inexplicably transforms into a real house. From then on out, Lynch drags the viewer down rabbit holes within rabbit holes (some of which literally contain rabbits, natch) filled with non sequiturs, mysterious thematic connections, and characters trapped in a tenuous bridge between film and real life. And all while this is happening, a mysterious woman watches the film’s events unfold on her TV, alone in her room, crying her eyes out.

This, I believe, is what makes Inland Empire Lynch’s most impenetrable film. The film is a mobius strip narrative in which the world of dreams/film and the world of reality/truth continually intersect, influence each other, and overlap, despite being part of the same plane of existence. Lynch’s other “dream narratives’ (Mulholland Dr., Lost Highway, and Eraserhead) were much different in execution. Both Mulholland Dr. and Lost Highway are rather explicitly divided into two “halves”, and become easier to really understand when you discover at what point the protagonist either enters (Lost Highway) or exits (Mulholland Dr.) the dream realm. Eraserhead, on the other hand, takes place entirely in its nightmare world without any hint of a waking moment, but the atmosphere and the not-too-subtle symbolism make it at least rather clear that we are, in fact, in a nightmare of some form.

Inland Empire doesn’t have that kind of clearly defined structure. In the world of Inland Empire, nightmare and reality might as well be one and the same.

This is mostly due to the film’s production, which was the most experimental in Lynch’s entire career. The film began shooting without a full script, with Lynch and the cast members, in some ways, “making it up as they went along”–though that’s too reductive a statement to make in regards to what they accomplished with this film. During each day of production, Lynch would give the actors a freshly written set of pages, and would repeat the process all the way up until completion. Meanwhile, Lynch would splice in scenes from his seemingly unrelated Rabbits miniseries, as well as pieces from a 70-minute monologue that Dern performed for Lynch prior to the film’s production.

This experimental shooting schedule is the reason Inland Empire is Lynch’s most inaccessible work. The dreamscapes in Eraserhead, Lost Highway, and Mulholland Dr. were very meticulously crafted, and each scene built off the other until it crafted something singular. That isn’t to say that Inland Empire is just a random barrage of meaningless vignettes. What it means is that this is the first time that Lynch had nothing but a premise to work off of, and instead of building the dream world from his own subconscious, he and the entire cast and crew decided to just dive into the rabbit hole and search for meaning along the way.

Upon the film’s release, some critics called the film “self-parody”. Perhaps those detractors are half-right, even if it is a disservice to Lynch’s singular sense of vision. Instead of a dreamscape of his own creation, Lynch himself is transported into this dream world, forced to look inward and make sense of it himself. With the film’s intentionally shaky, pixelated digital cinematography accenting Inland Empire‘s world of artifice, there is never a single point in the entire film where the audience doesn’t feel David Lynch’s hand in the events of the story. This is not because Lynch is in control of the story. Rather, for the first time ever, he is just as much a participant in it as his characters and the audience.

If Mulholland Dr. was a meta-reflexive commentary on Hollywood Dreams gone nightmarishly wrong, then Inland Empire is Lynch’s self-reflexive look at his own career, with every single one of his themes and motifs being utilized or even subverted: from the dualities of blondes vs. brunettes and dreams vs. reality, to the placement of red curtains and lamps in the scenery, all the way down to the film’s official tagline, “A Woman in Trouble”.

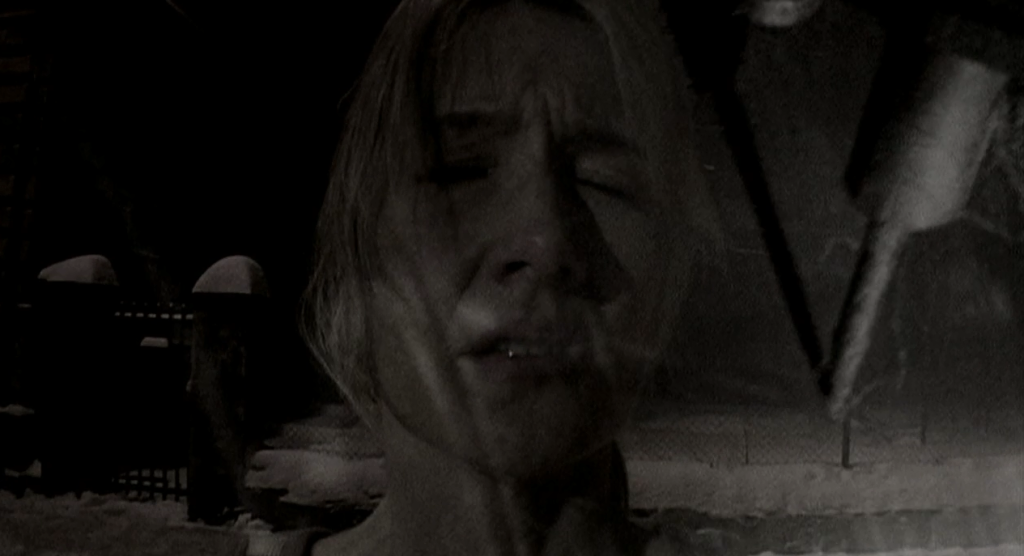

More than that, however, Inland Empire is simply a terrifying nightmare to lose yourself in. Even if I will never be able to parse out all of the intricate thematic connections and meanings behind the film, the disquietingly brilliant filmmaking that Lynch uses to explore this nightmare makes it so that I can never look away for the entire 3 hours. Many of the most terrifying images and scenes in all of Lynch’s filmography are packed in this one film. Some are quietly chilling like the “Inland Girls” dancing to “Locomotion” only to suddenly disappear for seemingly no reason, while others are some of the most expertly executed jump-scares in film history.

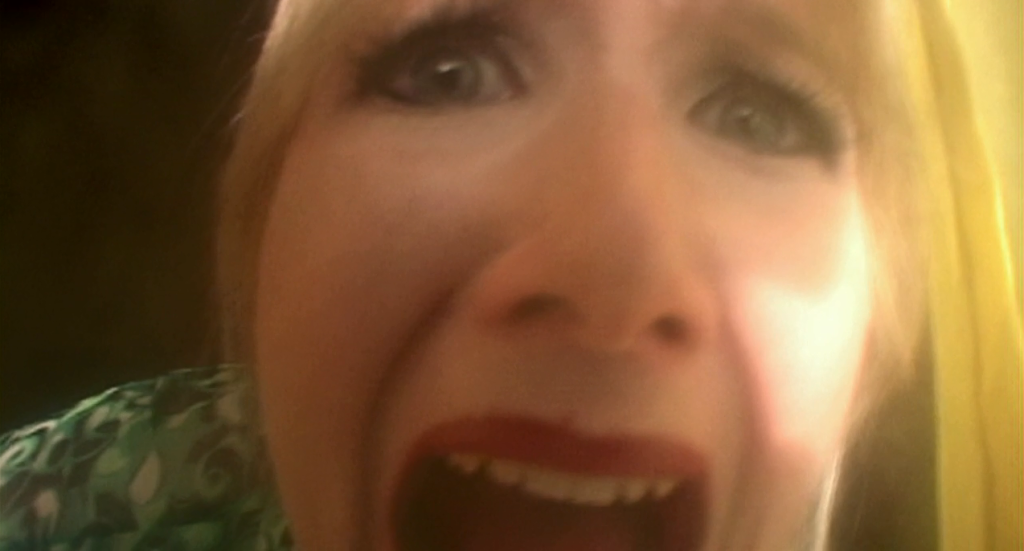

Further enveloping the viewer into Inland Empire is Laura Dern’s brilliant performance, which is arguably the best of her career. Dern once said in an interview that even she didn’t really know what to make of the film or how to interpret its events. I find that hard to believe, because as Dern is constantly switching between different variations of Nikki and Sue, she feels deeply rooted in each new persona. And though it’s rather hard to track down who exactly she’s playing in each scene, just the look of horror on her face as she confronts the incomprehensible is something that simply resonates, no matter your understanding of Lynch’s labyrinthine dream world. It’s a pure display of both her immense range and startling power.

This is especially true during the film’s tour-de-force final 30-40 minutes, where Dern’s Sue finally reverts back to Nikki and it’s implied that everything we’ve seen since she walked into the “set house” was just a cinematic fantasy of some kind. Dazed from her journey to whatever that “other side” was, she walks to a movie theater (playing back the actions she’s performing at the moment like a mirror) which transports her back to the “set house”, where she confronts whatever force it is that is bringing misery, emotional turmoil, and “trouble” to all of the women of the film.

This culminates in what is arguably the most terrifying scene Lynch has ever filmed, which I will let speak for itself with this YouTube link…

But the most perplexing thing about the film’s conclusion is not that horrifying scene, but rather what comes after it. Lynch follows up a scene of pure horror with something that we don’t see enough of in his filmography: beauty. The closing moments of Inland Empire are sublimely beautiful for reasons I can’t properly explain. I don’t know who these characters are, why they are rejoicing, or what kind of evil was haunting them before, but through the music and the images, I became wrapped in the film’s wave of emotions, as shining bright lights shone on Laura Dern’s face, giving her an almost Christ-like presence. All I’ll ever know for certain is that whatever darkness it was Nikki had to face as Sue in that fantasy space, it did something to “save” that mysterious woman who oversaw the events of the film in the television.

Could that be what Lynch is implying? That the act of creating film, or all art in general, is a journey into the darkest recesses of the soul? A draining odyssey through egos, ids, fears, and desires, all to bring happiness or sublimity to others the artist may never even meet or know? It doesn’t sound too far off. All of Lynch’s films celebrate the power of art in some way. Starting from the Lady in the Radiator singing “In Heaven, Everything is Fine”, influencing the scene in which John Merrick realizes his own sense of self-worth and dignity by watching a play in The Elephant Man, down to Blue Velvet‘s use of the song of the same name, continuing on to Wild at Heart‘s loving lampooning of pulpy American pop-art, and then reaching its apex in the repurposing of film-noir tropes in both Lost Highway and Mulholland Dr.

And like Diane discovering something about her Hollywood Dream in her fantasies, Inland Empire is David Lynch’s dream space. And in it, we see an artist, in this case an actress, using the power of fantasy to heal people of the real world, even if it means facing a dark, unimaginable terror. That’s the only thing that needs “explaining” in the world of Inland Empire. It’s the culmination of Lynch’s career as a filmmaker, whether he intended for that to be the case or not, and that it doesn’t feel self-congratualtory is even more remarkable. No matter what the film’s hidden meanings may be, what’s important is that we witness an artist finding meaning in his own art, trying to commentate on, and justify why it is the language of film speaks to us.

It is his 8 1/2. Like Fellini’s Guido, we see the creator himself tethered between the sky and the earth.

Lynch, sadly, still hasn’t directed anything since this 2006 film. Even to this day, responses to Inland Empire remain some of the most polarizing for any of his movies. This being the filmmaker’s most virtually inaccessible film, even fans of the director are more lost in the world of Inland Empire than they are in any of his other films. There’s been talks of a new film from the director, but the truth is, I wouldn’t mind all too much if Inland Empire was his final one. At 3 hours, even if it isn’t his most refined, complete, or even my favorite work of his, it is his magnum opus. A rumination on each and every one of his themes, obsessions, and even his whole career.

I will always hate Lynch giving me some of the most vividly terrifying nightmares that a film has ever given me. I will also always love him for being brave enough to take me to those nightmares in the first place.

Previous Editions:

Previous Movie Mezzanine Filmmaker Retrospectives:

The Darren Aronofsky Retrospective

The Terrence Malick Retrospective

And that is the end of the David Lynch Retrospective. Stay tuned in the coming months for another weekly filmmaker retrospective series from yours truly. Stay classy.

6 thoughts on “The David Lynch Retrospective: ‘Inland Empire’”

Great write-up. While I don’t think this series topped your impeccable writing on the Malick Retrospective, it was still very solid. I’m curious as to how you would rank his films from worst to best. Also, if you wanted to get a friend into Lynch’s films, which one would you recommend?

If you want a friend to get into Lynch films, you start with Blue Velvet, then Twin Peaks if he has the time to complete a full TV series, then Fire Walk With Me after that, and then slowly work his/her way up to the weirder stuff. Inland Empire should always remain last.

My personal ranking:

1. Mulholland Dr.

2. Eraserhead

3. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me

4. Blue Velvet

5. Inland Empire

6. The Straight Story

7. Lost Highway

8. Wild At Heart

9. The Elephant Man

10. Dune

Thanks for the list and suggestion. Keep up the good work.

You really nail what’s great about Inland Empire and the challenges of it. I saw this at the local college film series, and it really helped to watch it without distractions. I just let the images wash over me despite the fact that the story is impossible to follow. It isn’t my favorite Lynch film, but it’s in the upper tier for me.

Seriously, you are one fantastic writer! I greatly enjoy reading all of your essays,especially you’re retrospectives. I’ve read A LOT of film criticism, analysis, essays, etc. but reading your stuff has been the most excited I’ve been to read about film in a while, so thank you! I’m curious if you know what filmmaker(s) you are planning on doing a retrospective on next, or if you’ve even thought about it yet.

I have a few picks, but I don’t know which one I’ll decide on for sure yet.