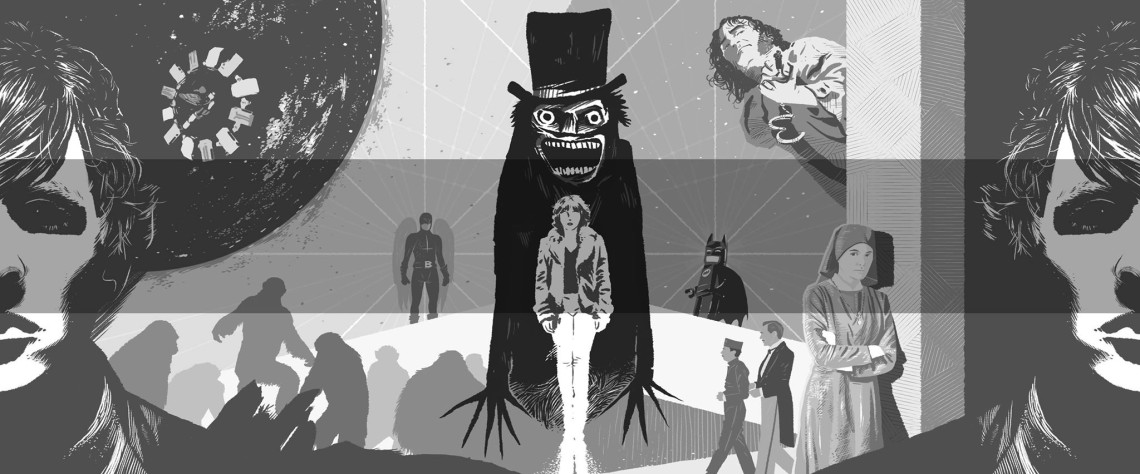

The Babadook is that rare creature: a horror movie with a brain and a heart. (And, not to mention, nerve.) Writer-director Jennifer Kent’s debut feature is a stylish, spare, and almost effortlessly unnerving haunted house story, but it’s the reasoning behind that story that makes the film so powerful. The titular Babadook isn’t a random monster inflicting fear on hapless victims, but the physical manifestation of the grief and regret of a harried single mother, played with compelling abandon by Essie Davis. As opposed to the mindless killer of a slasher film or the grotesque

m.c. of a torture porn circus, the monster here is inextricably linked to the main character’s emotional choices. Her refusal to confront a tragedy in her past has called into a being a monster that feeds on her fear. Kent’s eerie fable is a profoundly human one: What do we pretend not to know? What do we pretend not to cause? Shot with style to spare, and always interested in real fear instead of cheap jump scares, The Babadook is a frightening, fantastic movie about the lengths we travel to learn how to live with ourselves. — Carlson

Two old souls grow weary of the hollowness and decay of the world around them. No, I’m not describing your grandparents; it’s Jim Jarmusch’s latest take on aging, the passage of time, and his cinematic legacy, Only Lovers Left Alive. Adam (Tom Hiddleston) has tired of this vacuous realm and seeks to leave immortality, but his dearly beloved Eve (Tilda Swinton) rushes to his side from another part of the planet to show him that all hope is not lost and there’s more to live for. Jarmusch flavors his movie with historical and cultural references right alongside his

own film works (including a drive past Jack White’s old home), and sets the meandering tone with hypnotic beats from his own band. Moments of quiet reflection and musings pause for Mia Wasikowska and Anton Yelchin to make pleasant cameos. Ultimately, it’s Swinton’s and Hiddleston’s chemistry that introduces you into their never ending world and makes you never want to leave. Vampiric elements be damned, this is a real love story. — Monica Castillo

Writer-director Alex Ross Perry’s scabrous portrait of authorial assholery in these waning days of literary-world relevance playfully re-arranges component parts from Philip Roth’s The Ghost Writer, with Jason Schwartzman starring as an up-and-coming novelist compulsively trashing his personal relationships in the name of ascetic artistic ideals that are probably just a more pretentious form of selfishness. Structured like a novel, with a wonderfully knowing third-person narration read by Eric Bogosian, Listen Up Philip is a cutting tour-de-force of cringe comedy headlined by Schwartzman’s most dyspeptic performance yet. Jonathan Pryce plays an even bigger blowhard –

co-starring as a once-great author fading into irrelevance and loneliness. He takes this kindred, sour spirit under his wing and offers a grim glimpse of Schwartzman’s future. Departing for chapters at a time from our self-obsessed protagonist and his disdainful mentor, Perry sees a larger world beyond their cloistered, narcissistic prattle. There’s an achingly beautiful performance from Mad Men’s Elisabeth Moss as the photographer girlfriend left behind, and strong work from Krysten Ritter as Pryce’s neglected daughter. Listen Up Philip finds melancholy in misanthropy, and by the time the credits roll, the funniest movie I saw all year has also become one of the saddest. — Sean Burns

Few films in 2014 sparked more vigorous debate than the latest lurid masterpiece from director David Fincher. Adapted from Gillian Flynn’s page-turner of the same name, Gone Girl sees Fincher picking at a familiar scab of masculine delusion that he did in Fight Club, Zodiac and The Social Network, while also casting his sardonic lens on marriage, the media and blinding social privilege. Set amidst the McMansions of Middle America, the film starts out as an easily digestible whodunit, only to turn the formula on its head at the beginning of the second act. The result is a film that manages to be both gripping and

insightful– not to mention, surprisingly funny. After ten outings, Fincher is a filmmaker in full control of his aesthetic, accentuating the movies’ delightfully delirious vibes via emotionless cinematography, hypnotic editing and the skin-crawling dissonance of the Trent Reznor/Atticus Ross score. Affleck gives a career-best performance, presumably informed by his own less than comfortable experiences with the press. At this point, however, it almost goes without saying that the movie belongs to Rosamund Pike. — Tom Clift

James Gray’s early films evinced strong ties to the halcyon days of New Hollywood filmmaking, not only in their formal rigor and revisionist narratives but, less laudably, their near-total inability to depict women as anything more substantial than bystanders or martyrs. Two Lovers considerably rectified this issue, but with The Immigrant, Gray has reached a new creative plateau timed with his first movie truly centered on a woman. The director’s younger self might have been content to portray Ewa (Marion Cotillard) as a beacon of suffering, but Gray instead sets up the Polish immigrant as a woman fiercely aware of her circumstances who is able to compartmentalize the horrid abuse she suffers as a powerless figure. Cotillard hones in on this aspect, lending an

Old Hollywood regality to Ewa that sketches the character as the greatest part Gloria Swanson never got to play. That classicism rubs up against Joaquin Phoenix’s new-wave method brutalism as Ewa’s pathetically smitten pimp, juxtaposing her strategic submission with his jittering id. The film as a whole reflects this contrast, indulging Hollywood’s use of nostalgic sepia tinting for period pieces while thematically perverting it with an emphasis on the obscuring nature of nostalgic photography. Gray may have started out living up to the legacy of 1970s filmmakers, but here he proves that he could have stood toe to toe with all of them, and even surpassed all but the most accomplished and far-seeing. — Jake Cole

Two Days, One Night feels like the kind of parable Jesus would tell if he were around in the here and now. The movie tells his kind of lesson, one that seems obvious, but might prove difficult to put into action were any of us faced with the choice to do so. And it’s infused with a very Christ-like sense of grace and compassion for every kind of human being. It’s such a basic story, never deviating from where it promises to go in its opening minutes: Sandra has been fired because her coworkers were offered a good bonus if they made her redundant, and now she must visit each of them and beg them to give up those bonuses so that she can have

her job back. Each encounter between her and one of her coworkers builds up raw emotion, culminating in a finale whose raw catharsis seems impossible, given how low-key it is. But that’s the power of the moral victory that Sandra achieves in the end, a graceful, beautiful action. It’s the payoff to Marion Cotillard’s titanic lead performance, which embodies the movie’s ethos: potency through simplicity. Which is a hallmark of director brothers Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, who never play a moment one whit louder than it needs to be. This film speaks emotional volumes without ever raising its voice. — Dan Schindel

Wes Anderson presents The Grand Budapest Hotel as history, one of many untold stories swept away by Time’s raging tide. At the center of the film is the story of M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes), the head concierge at the eponymous hotel during its glory days in 1932 in the Republic of Zubrowka, a fictional European alpine state on the brink of war. He’s framed for the murder of the wealthy Madame D (Tilda Swinton) and soon him and his trusted lobby boy Zero (Tony Revolori) are off on an adventure to clear his name. However, Anderson addsa melancholic edge to the proceedings by refracting the story over

three different decades, illustrating not only the story’s age but also the effect of time has on its tellers. Though The Grand Budapest Hotel veers from slapstick comedy to muted drama, Anderson’s ode to storytelling and its ability to keep wrinkled histories of bygone eras alive resonates throughout the film. The story of Gustave and Zero would have been lost if not for The Author, and it would be dead if not for an unnamed girl reading about it decades later. No one ever gets a full picture of the past, but Anderson understands the brief glimpses we do get are worth preserving. — Vikram Murthi

For all the pre-release chatter about the Herculean task of mounting the first straight adaptation of Thomas Pynchon, what impresses most about Paul Thomas Anderson’s warm and shambling Inherent Vice is the extent to which it is so plainly an auteurist project. Though it trades the seedy San Fernando Valley night clubs of Boogie Nights for the earthier locales of a slightly fictionalized Manhattan Beach, Inherent Vice undoubtedly bears Anderson’s signature—not just in its natty formal construction and interest in the eccentrics loitering in the margins of the recent history of Los Angeles but in its earnestness about the pain of

inarticulate blockheads. If Joaquin Phoenix’s gumshoe Doc Sportello is a sprightly comic invention, a stoned Bugs Bunny to the implacable Elmer Fudd of Josh Brolin’s Bigfoot, it’s Bigfoot who becomes the film’s unlikely centre, anchoring Inherent Vice in Anderson’s familiar melancholy about the past. A straightedged LAPD officer who simultaneously hates and yearns for something in Doc’s easygoing bearing, Bigfoot’s ambivalence—beautifully played by Brolin—feels like the key to Anderson’s depiction of 1970 as a threshold that nobody will pass through unscathed. — Muredda

The argument as to why we make films at all will go on until the medium implodes, and rightfully so. But a compelling case could be made that art aims to replicate the human experience. Operating under this premise, Boyhood is the closest that film has come to nailing that mark. Richard Linklater’s twelve-year chronicle resonates because it doesn’t mold its narrative to fit lofty statements about the Human Condition™. It defiantly shuffles off the three-act structure, but doesn’t get mired in rambling inaction. Stuff happens, then other stuff happens, then more stuff happens. People insinuate themselves in Mason Jr.’s life,

then leave it. Little bits of ephemera—haircuts, musical tastes, clothes—change, but his personality remains the same. In one scene, Mason and his buddies kill time by whipping rusty saw blades at a plaster wall. Hollywood has spent innumerable lifetimes ingraining in the viewer that these beer-sipping kids are about to learn a valuable, gory lesson about irresponsible equipment handling. Instead, nothing happens. They keep goofing around, shooting the shit, and the time code ticks steadily on. Such is Boyhood, and such is life. — Charles Bramesco

Based on a 2000 surrealist novel by Michel Faber, Glazer’s film is set in Scotland and tells a story of a mysterious woman, presumably an alien, who lures lonely men into her lair and collects their bodies. These are the narrative facts, but of course the film can be easily interpreted on a more metaphorical level with Glazer’s thoughtful, climatic execution facilitating and encouraging such an approach. He maintained to preserve the prose’s almost opaque character, but has shifted focus, depriving the cinematic adaptation of many details that defined the book.Therefore, instead of a dark, politically, environmentally and socially involved semi-satire we get an intense, surreal vision, posing complex questions about identity, sexuality and humanity. Stripped of the Hollywood glitz and glam—and, for the most part, of dialogues as well—Scarlett Johansson is mesmerizing. Calm, silent, focused, her nakedness barely erotic, coding first power then powerlessness. Watching the character on her journey is witnessing a predator becoming a prey the

moment they let their guard down and allow the notion of humanity, therefore doubt, seep into her. When she becomes vulnerable, so does the skin she lives in. Under the Skin is masterfully executed, camera work and editing right on point. But despite this exceptional visual awareness it retains its natural fluidity and at no time feels fake or forced. Images of majestic Scottish nature mark subsequent stages of the character’s quest. Foaming, raging sea, murmuring, tottering pines, delicate, yet deathly frost: they all develop personality because of the sound that accompanies them. Ominous and disturbing, it repeatedly gains momentum. Nature’s vital innocence is crushed, innocent images turn into lurking vultures only waiting to attack. Johnnie Burn’s exquisite sound design and Mica Levi’s hypnotizing music elevates the film to a truly unparalleled level. Under the Skin is well worth revisiting, taking on an entirely different journey with each screening. — Anna Tatarska