Any Filipino who grew up as a kid in the early 80s will tell you about their love for giant robots. As a country that was once invaded by Japan, it can seem strange that Philippine culture would wholeheartedly embrace an invasion of mammoth-sized mechas during the time of Marcos. Mekanda Robo, Mazinger Z, Daimos, Gaiking, Grendizer, Macross. These animated wonders filled our large imaginations long before their American counterparts came along in the Gobots, Transformers, Robotech and Voltron. I suspect that many of my compatriots know the Japanese lyrics to Voltes V by heart as much as we do our national anthem.

So you can imagine dear reader how much anticipation I held for Pacific Rim the moment I understood its ambitions. With its clear Asian inspirations (the title alone is a dead give away) and superlative director, my heart was aflutter. If Guillermo Del Toro could give soul to a demon (Hellboy), surely he could do no less with machines.

He does. In spade after spectacular spade. So much so that the film’s intro is better than any other summer blockbuster this season. In those 15 minutes, we dive into an alternate earth where Kaiju, titanic beasts from the ocean floor (originating from an inter-dimensional portal), terrorize global populaces with increasing numbers and frequency. Humanity responds with the Jaeger program, aptly named for the robotic hunters created to repel the monstrous wave. By the time this mesmerising prologue ends, the tide turns.

The jaegers are controlled neurally, but are each too complex to be driven by a single pilot. Thus a system of “drifting” does the job, where compatible pilots each represent a hemisphere of the big bot’s brain. Both parties enter a mind-meld where each can inhabit their partner’s emotions and memories. This is the film’s most fascinating creation, not only due to the implications for its story, but also because it serves as a remarkable device for audience empathy. The moment one jaeger pilot experiences a jarring event, we immediately consider what ramifications it has on his/her co-pilot, and on the context in which they both operate.

Such events usually occur in combat with the kaiju, which here, as par for the course under the director’s eyes, are beautiful in their monstrosity. Del Toro is a master in designing the ugly, with musculatures that feel wholly original yet familiar in nature. He knows how to hide them appropriately in the shadows and use light to reveal their bits and pieces in just the right doses. He loves the sharp teeth, the extended claws, the grime and the slime. No filmmaker is wiser in making us respect the nature and danger of his beasts, and no one is more devilishly funny in making us think we are safe from them.

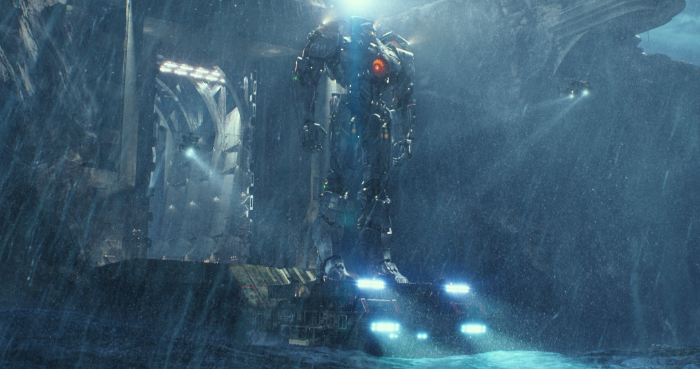

What is surprising here is how much he affords the same love and detail to his colossal contraptions. Consider the Iron Man films, where shiny metallic heroes also grace the screen. Del Toro goes beyond this not just in terms of size and scope, but in wear and tear. We see and hear the chipped-off paint, exposed wires, lackluster metal and grinding gears. It’s clear that Del Toro values the scruffy over the sleek, like an old pair of shoes you can’t bear to part with.

This mastery over the finer things extends to his Brobdingnagian battles, dwarfing the scale of any mano-a-mano melee that I can recall. The size and heft of kaijus and jaegers are consistent throughout the film, amplified greatly by Industrial Light and Magic’s CGI renderings of lighting and environment. Their battles extend from the ocean floor to the stratosphere, with a digital Hong Kong serving as luminous squared circle. Though I do wish there was at least one battle envisioned in the daylight (fat chance of that in a Del Toro film), there are no murky battles in the dark and no unnecessary shaky cam perspectives. Del Toro understands that in a movie about giants, clear money shots bathed in epic scores (solid work by Ramin Djawadi) are gold. In this sense, the film is Fort Knox.

The battles themselves will inspire huge smiles among lovers of japanese mechas. Though the robots themselves were purposely designed not to directly evoke any influences, references abound, particularly in controls, weaponry and the need to vocalise their usage. But what I admired most about the conflict was how genuine the stakes felt. Unlike the Transformers franchise where no life, mechanical or human, ever feels as if its at stake, Del Toro quickly makes it known that monsters are exactly that. Horrifying death never seems too far away when the jaegers do their duty.

But grim matters are not on the director’s mind. In a summer season where tentpole films have become perhaps too concerned with realities their audiences try to escape from, Del Toro doesn’t beat us over the head with it. Iron Man 3, Man of Steel, Star Trek Into Darkness, and World War Z all remind us of various topicalities, ranging from religion, terrorism, politics, and disease. Pacific Rim, despite its semi-propagandistic marketing, feels nothing of the sort. It is made purely for the kid in all of us who longs for the larger than life, but now knows better. It contains mass destruction, but doesn’t linger like a fatalistic voyeur. It wants to awe us with what we’ve wanted to see, but it also reassures us in the end that it’s all in good fun. Maybe it’s timing. But it sure is refreshing.

What’s also refreshing is how Asia-centric it feels. Rarely has an American blockbuster paid homage so soulfully and lovingly to its Pacific-based inspirations since The Last Samurai. Another manifestation of this respect is Del Toro’s casting of Rinko Kikuchi as Mako Mori, co-pilot of the lead jaeger. Her wide eyes convey a buried intensity that is impossible to look away from. Perhaps he got a call from his fellow compatriot and good friend Alejandro González Iñárritu to have her cast? After all, all she did was get nominated for an Oscar in Babel.

The rest of the cast is solid, notably Charlie Hunnam who plays the lead Raleigh Becket; Idris Elba who plays the satisfyingly named Stacker Pentecost; Charlie Day who plays the loquacious yet likeable scientist Dr. Geiszler; and of course Ron Perlman who deliciously plays Hannibal Chow. What would a monster-themed Del Toro movie be without the Perl?

Yet make no mistake. The towering football field-sized heroes and villains of the movie are its stars. And we are never deprived of seeing them in all their glory. Pacific Rim is an astoundingly joyous spectacle. If only Guillermo Del Toro’s contemporaries could remember how to give audiences a roaring good time at the movies like he does. Can we please have him direct everything now?

2 thoughts on “Guillermo Del Toro’s Rousing ‘Pacific Rim’ Is a Joyous Homage to Pacific Inspirations”

I lost it when the Gypsy Danger brought out its sword. And it did its own final blow pose no less. After the movie, I was wishing it had its own theme song I could immediately elevate into anthem status and cannot help but sing it whenever it plays.

At that point, I thought, “HOLY SHIT. They even brought the swords.” Del Toro has me for good.