A record bathed in blue is spinning. The needle grazes overhead. It drops, and the scene is taken over by a blank black screen. A wilting jazz number plays over the unpainted canvas, and it’s the only thing to the audience has to grab onto in the darkened theater for a few seconds before a tiny date appears in the lower-left corner: May 17, 1959.

Thus begins a loosely structured look into the life of controversial critic Nat Hentoff. Born and raised in Boston, the Northeastern grad made a ruckus wherever he went. Eventually landing at the Village Voice and several of New York City’s esteemed jazz papers, he championed the works of Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, and several others to a public that hardly understood jazz let alone the players. As a fierce First Amendment activist, Hentoff stood up for the civil rights movement and for the rights of Neo-Nazis to march in Skokie back in the 70s.

Now, that’s a chronological approach to telling Hentoff’s story. Director David L. Lewis does otherwise. He scatters the biography throughout, apparently to mimic the improvisational jazz in the background. The key issue that, for better or for worse, Lewis is stuck telling a story, one with certain beats and rhythms the audience uses to follow along. The free-wheeling jazz numbers aren’t so much about story or structure as they are about feeling and one’s reaction to that work. Lewis’s nonlinear approach jumps throughout his subject’s life so many times, there just aren’t enough dates listed to give you a sense of the passage of time. It becomes difficult to follow Hentoff’s climb into infamy as it appears it all happened spontaneously.

Aside from being out of step with The Pleasures of Being Out of Step, the movie plays like a greatest hits collection from several of jazz’s legendary founding fathers performing on soundstages in better quality than you can track down on YouTube. Lewis captures the sounds and sights of the era effectively, giving weight to Hentoff’s old reviews and supporting his testimony from other jazz critics, musicians, and former Village Voice staffers. Lenny Bruce also makes a few appearances, extolling the virtues of the Village Voice and fielding on-stage questions.

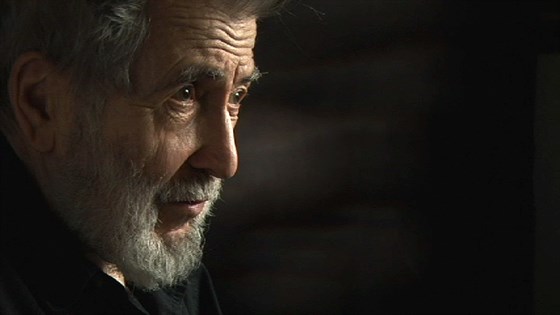

The critic at the center of this culture milieu, Nat Hentoff, is a wild card in his own right. He’s in his 80s now, still wryly making jokes and undercutting those he doesn’t respect. “I found out that having a byline can quickly make you an authority to people who aren’t very intelligent about authority,” he laughs at the start of the movie. For all his fervent belief in free speech, he came out against abortion rights. Claiming that since he was against war and capital punishment, Hentoff argued that he was against all forms of premature death. The reason behind this turns out to be much closer to human fallacy than ideological righteousness. Several associates appear in the documentary, to add their falling-out story with the writer. Hentoff casually name-drops like it’s nobody’s business, quickly adding “my friend Duke” or “my friend Lenny” to any conversation. It’s safe to assume he’s probably not the easiest to have over for tea.

Lewis might have been out of step with the storytelling, but the interviews and archival footage slickly strengthen Hentoff’s tale. A young announcer by the name of Rev. Andrew Young is the first to appear on-screen during an old CBS segment. That first date listed in the corner is his to set the tone for the movie to follow. Rev. Young describes jazz as the “emotional language of this generation.” While it seems almost everything else Nat Hentoff has to say has a ready rebuttal, no one argues this point otherwise. For as argumentative and combative as the hell-raiser is, there’s a sort of respect that follows when it comes to his views on jazz. He brought several musicians to television, wrote extensive liner notes for their records, and covered their club appearances in a way few reporters did at the time. In this sense, he might have been out of step with the establishment, but he was every bit on beat where it counted.

One thought on ““The Pleasures Of Being Out Of Step” Misses A Beat Or Two”

“…he came out against abortion rights. Claiming that since he was against

war and capital punishment, Hentoff argued that he was against all forms

of premature death. The reason behind this turns out to be much closer

to human fallacy than ideological righteousness.”

what is the reason exactly? it kinda stumped me when pro-lifer Hentoff supported the Iraq war.