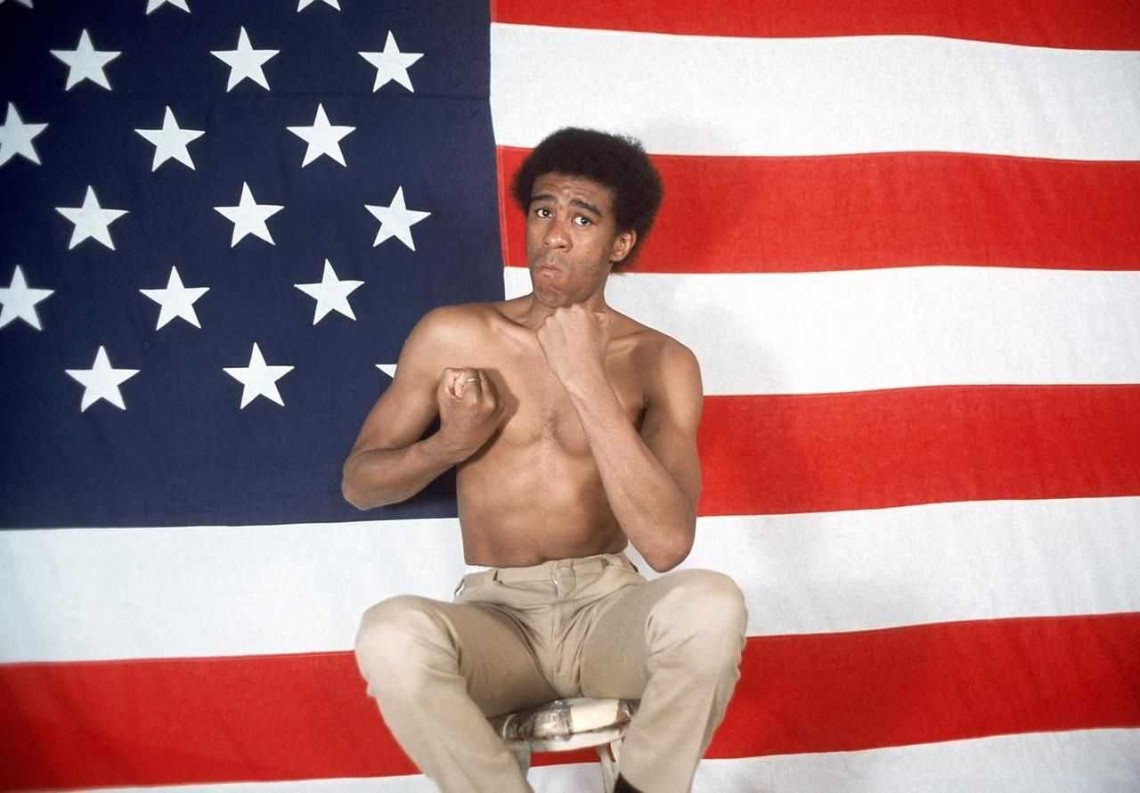

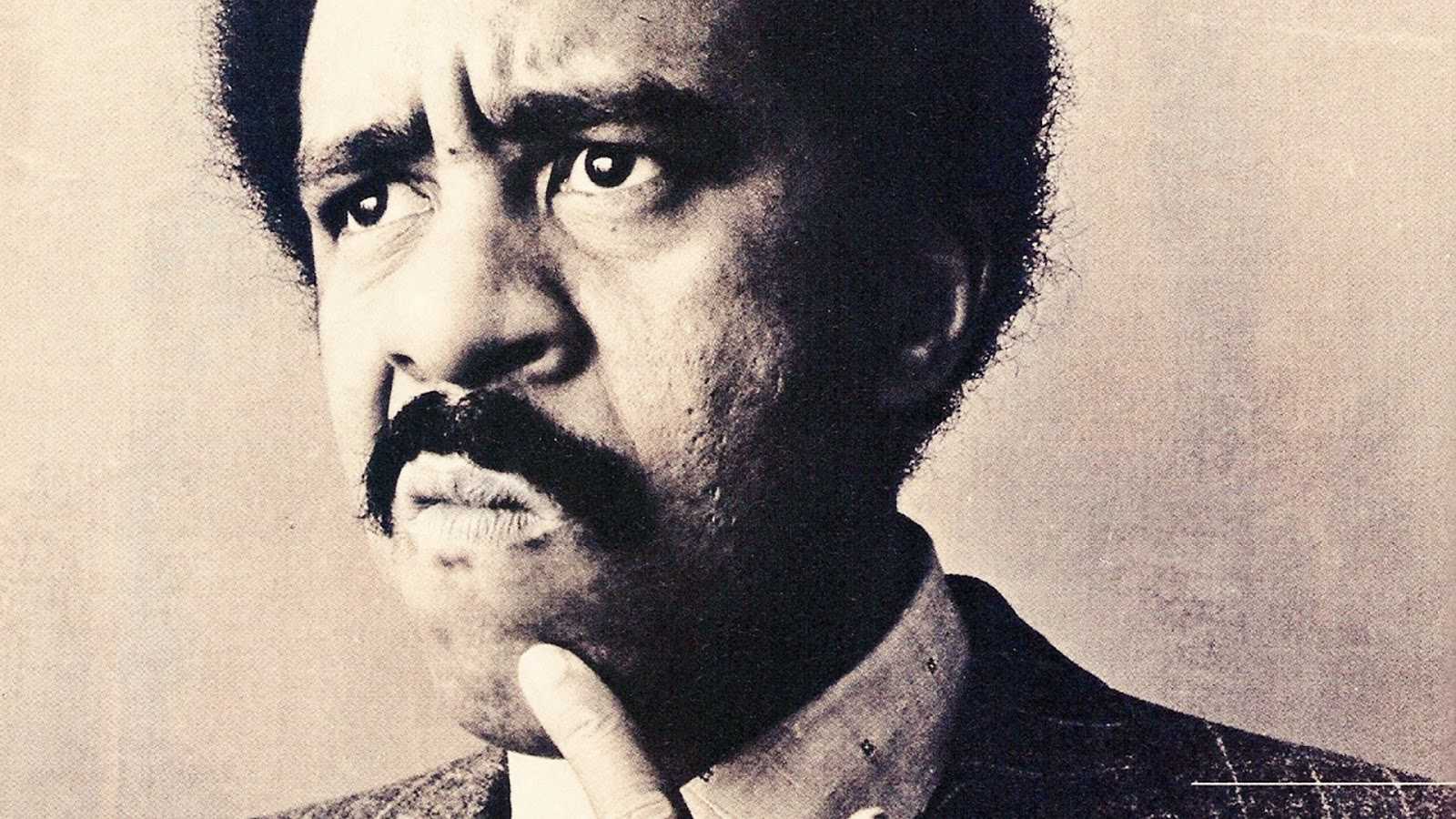

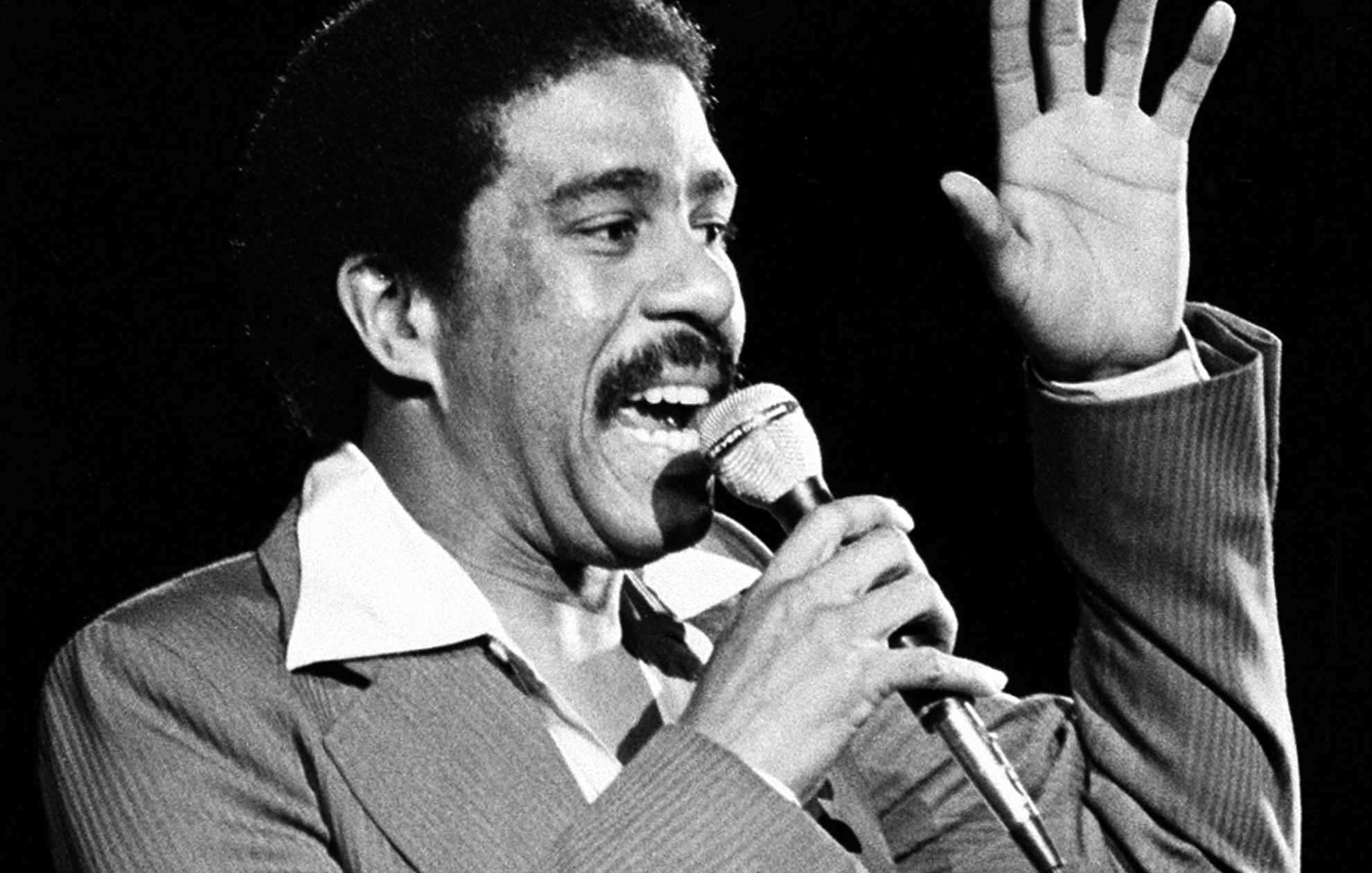

Editor’s note: Today, we’re proud to present readers with an exclusive passage from Jason Bailey’s book Richard Pryor: American Id. Be sure to pick up the book up now that it’s available for purchase from The Critical Press.

In the short stories collected in his 1899 volume The Conjure Woman, mixed-race author Charles W. Chesnutt tells the tale of a white couple from the North and their interactions with a “colored coachman” on their Southern farm. They dub the former slave “Uncle Julius,” and he regales them with “stories of plantation life . . . some weirdly grotesque, some broadly humorous; some bearing the stamp of truth, faint, perhaps, but still discernible; others palpable inventions, whether his own or not we never knew, though his fancy doubtless embellished them.”

Uncle Julius was one of a popular type, in Southern literature toward the end of the nineteenth century and well into the next: the grizzled but cheerful old black man, telling tall tales and spinning yarns of the ol’ days. The best-remembered of them today, thanks primarily to the notoriety of Disney’s let’s-pretend-like-we-didn’t-make-this 1946 film Song of the South, was Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus, but there were plenty more: Zora Neale Hurston’s Daddy Mention, Frances Harper’s Uncle Daniel, Bert Williams’s Spruce Bigsby. Williams described Bigsby thus: “He can’t read. He cannot write. But ask him a question and he’ll answer it with a philosophy that’s got something.” He also characterized Bigsby as “the shiftless darky to the fullest extent”; lines like that, and Chesnutt’s descriptions of Uncle Julius hoarding honey and stealing watermelons (to say nothing of headache-inducing dialogue like “But ef you en young miss dere doan’ min’ lis’nin’ ter a ole nigger run on a minute er two w’ile you er restin’, I kin ’splain to you how it all happen’ ”), reiterate that while the characterizations of white writers like Harris might’ve been more blatantly demeaning, they hadn’t cornered the market on negative stereotypes. Many of these characters, even when flowing from the pens of black writers, perpetuated what historian Mel Watkins calls “the carefully fabricated myth of genteel plantation owners and contented slaves with nothing but fond memories of bondage, which was created by Southern writers after the Civil War.”

In Pryor Convictions, Pryor describes meeting his most famous character one night onstage, when he just appeared, “right there, waiting for me to notice . . . I suddenly knew everything about this wise old man who I called Mudbone. Every black town had someone like him. Some old geezer who talked shit about his life’s experiences. Fancied himself a philosopher.” Pryor did two minutes of Mudbone that night; by the time he recorded his next album, he was handing the old man the mic for eighteen minutes.

“There was a old mayyyn,” he told his audience, “his name wuh Mudbone, and he’d dip snuff and he’d sit in front the barbecue pit, an’ ’ee spit, see? That wuh his job. I’m pretty sure that wuh his job, see, ’cause that’s all he did. But he’d tell stories, fascinatin’ stories, see?” Mudbone speaks in a rich Southern vernacular (“they blame’t it on me,” “Commenced we went over there,” “She ain’t got on no bah-zeer,” etc.), shading in the smallest of details (“bootleg haircuts” to pass as Chinamen, earning “that funny Yang money”), and weaving a bizarre narrative that marks him a fabulist, from his far-out conjure tale to impossible claims like driving “746 mile on one tank o’ gas!”

“There was a old mayyyn,” he told his audience, “his name wuh Mudbone, and he’d dip snuff and he’d sit in front the barbecue pit, an’ ’ee spit, see? That wuh his job. I’m pretty sure that wuh his job, see, ’cause that’s all he did. But he’d tell stories, fascinatin’ stories, see?” Mudbone speaks in a rich Southern vernacular (“they blame’t it on me,” “Commenced we went over there,” “She ain’t got on no bah-zeer,” etc.), shading in the smallest of details (“bootleg haircuts” to pass as Chinamen, earning “that funny Yang money”), and weaving a bizarre narrative that marks him a fabulist, from his far-out conjure tale to impossible claims like driving “746 mile on one tank o’ gas!”

In offhand fabrications like that, and especially in Mudbone’s description of his relationship with “my partner, Tudlum,” the first pieces introduce the theme of “tellin’ lies”—an experience not just key to the Mudbone character, but to the roots of African-American humor. An all-purpose term, “lying” encompasses not just fabrications for self-interest, but tall tales, signifying, and telling jokes. He classifies the “niggas with the big dicks” joke as a “lie,” and its telling is instructive of not only the flexibility of the term, but Pryor’s immersion in the character, because Mudbone tells a joke differently than Richard Pryor does. He states the premise several times, and after delivering the punch line, he repeats it to himself, chuckling—just the way old people do.

By the time the character returned, on the following year’s Bicentennial Nigger album, he was already a fan favorite. His introduction matches, almost word-for-word, that of the previous record: the aged voice in place, announcing “I wuh baaahn . . .” Those three words make the audience go wild, just as they do when his preacher character opens the show with his refrain “We are gathered here tuh-day . . .” In fact, the preacher only gets the first two words out before they go nuts. These were, oddly enough, catchphrases; if Pryor were working today, they’d be on T-shirts.

This time, we find out more about Mudbone: that he gets up early in the morning to hear the birds sing (“they tell you what happened last night,” he explains, echoing the anthropomorphism of the antebellum animal tales that held a similar place in black oral tradition), that he served in France in World War I, and that he did a stint in Hollywood, which came to a quick end when he sliced a lackey’s arm off. The arm’s behavior—existing separate from the body, pointing at its former owner—is one of many examples of the surrealistic storytelling that’s unique to Mudbone in Pryor’s repertoire; those touches appear often while he’s spinning Mudbone’s yarns, though far less frequently in his own.

When Mudbone next appeared onstage, in Live on the Sunset Strip, he wasn’t there to tell his own story—he was there to tell Richard’s. Pryor steps outside himself to convey the enormity of his own excess; there’s no better way to do so than by framing them in Mudbone’s straight-shooting terms. “He fucked up,” Mudbone tells Pryor’s audience. “Fried what little brains he had.” He dispenses his customary folk wisdom (“There ain’t but two pieces of pussy you gonna get in ya life. That’s ya first and ya last, and all that shit in between don’t count. That’s just the extra gravy, y’see”), tells a far-fetched story of hardship (“It was dark all the time. I think the sun came out on Wednesday, and if you didn’t have yo’ ass up early, ya missed it!”), and speaks in distinctive down-home colloquialisms (“Wouldn’t ever gimme five, but he lemme have those twos and fews, you know”). But he makes it clear early on, “I am not gonna steal the show from the boy,” and he doesn’t. In fact, his appearance is a clever structural tool; by using the voice of Mudbone to bring up his recent troubles, he leans the audience toward the show’s third act, and his candid discussion of those troubles.

Here and Now documents Pryor’s final major tour; by now Mudbone’s appearance is not only expected but demanded, and he seems oddly invigorated by the unruly audience (when someone whoops after his mention of running buddy “Sweet Chocolate,” Mudbone replies, “You know Sweet Chocolate?”). He entertains them for ten minutes, and at the end, when someone hollers out that they love him, he replies, “Shit, I love you too. It’s easy to love somebody. That’s all you got to do, sit with ’em for a little while, talk to ’em.” In that moment, he succinctly summarizes what he’s spent those seven years doing with Mudbone—sitting with him, talking with him, since, as he mentions in that very first introduction, “you learn stuff listenin’ to old people. They ain’t all fools, you know. You don’t get to be old bein’ no fool.” And that notion, in its own simple way, gets to the bottom of oral folktales and Southern storytelling, passed down from generation to generation, old folks to young ones. Some told their stories around campfires, in pool halls, or around the dinner table; Mudbone told his in theaters and nightclubs.