Twenty-five years ago, before the “golden age of television” was ever christened, Krzysztof Kieslowski blessed Polish TV sets with his majestic work The Decalogue, a series of 10 short films loosely based on the Ten Commandments. It was a distinctive cinematic feat, garnering massive acclaim for its scope and artistry in 1989 (though not necessarily from the Polish public), which subsequently received a theatrical run in Europe with screenings on the festival circuit. Despite its critical success, this marriage of cinema and television faced distribution problems and never found the exposure among the masses it deserved. Over the last 15 years, though, it has slowly bled into cinemas and homes across the world thanks to a 2001 DVD release from Facets and limited theatrical runs.

Each chapter in the series is based on one of the Old Testament’s Ten Commandments. Most, if not all of them, should ring familiar to the general viewer, ranging from “You shall have no other gods before me” to “You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain,” from “Honor your mother and your father” to “You shall not murder.” But instead of copying and pasting the commandments into religious tales of morality, Kieslowski and frequent writing partner Krzysztof Piesiewicz take the laws out of their Biblical context and embed them in the messiness of real lives. Characters are given the room and space to actually live, be it through failure, pain, suffering, or loss. By doing this, the work as a whole makes human experience seem as sacred as religious life.

Originally a documentary filmmaker, Kieslowski’s roots are evident as his camera plays in a heightened realism set in an apartment block of cold, frigid Warsaw. It peeks around corners and through closets, with the work’s themes hammered home in shots of characters examining their own images in mirrors or the camera studying them through their windows framing their interior lives. The Decalogue is thus itself a window, and as the viewer peeks through the facades, lives are laid bare to show both who these people are and who they long to be.

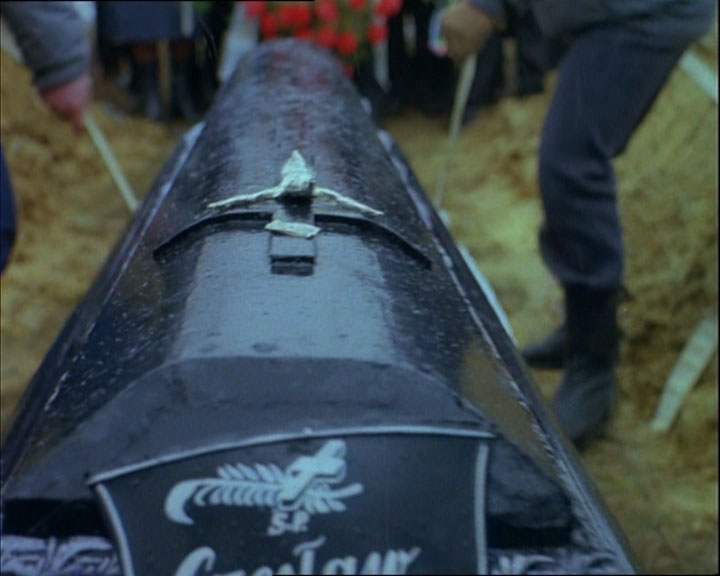

One of the most harrowing and ethically muddled films comes in Decalogue V (“Thou shall not kill”). The film depicts the murder of a man by a Warsaw youth lost in the streets, clearly a punk kid shaped by a life full of neglect. His act of killing is heinous, but Kieslowski doesn’t leave the viewer simply to judge the boy. Instead, he forces his camera into the ruthless after-effects of the murder: the boy’s journey to execution viewed through the eyes of the lawyer who defends him. The film brings into question the pitiless ideal of retributive “eye for an eye” justice. The boy dies, and the lawyer is left contemplating the very system he works in. What does humanity learn from judgment as seemingly cruel and unforgiving as the initial act of murder itself?

Each short brings similar ethical questions to mind, though not all are as harrowing in tone. Kieslowski communicates these tonal shifts by his choice to use a different cinematographer for each film and in the way he delicately crafts the unique issues each character faces. For instance, Decalogue IV (“Honor thy mother and father”) takes the form of a Brian De Palma-like Freudian thriller as a father and daughter fall into the odd space of sexual attraction and desire after the death of the family’s matriarch. And after nine episodes of dense material, Decalogue X (“Thou shall not covet”) ends the series with a blackly comic tale about two men, who after the death of their father, come across his very valuable stamp collection which they attempt to complete, one of them literally giving away a kidney in exchange for a stamp.

In navigating these ethical spaces, The Decalogue serves as art truly imitating life. If anything, it’s fitting that most people have experienced the series in the privacy of their own homes; viewers invade the lives and struggles of these characters and by doing so, have these struggles become their very own.

The story goes that the idea for the series came to Kieslowski’s writing partner Piesiewicz one day while looking at a 15th-century painting which set the commandments in the context of the piece’s own time period and suggested that a modern equivalent must be made. It seems that The Decalogue has fulfilled its creators’ intentions, for it is a work of daring, transcendental cinema, revealing the weightiness of life. In his beautiful review of the series, Roger Ebert said, “At the end you see that the Commandments work not like science but like art; they are instructions for how to paint a worthy portrait with our lives.”

With its spurts of distribution, The Decalogue has had the unique privilege to be critically reassessed every few years as more and more people are awakened to the work’s brilliance. Its relative obscurity seems a shame given its craftsmanship, but in the grand scheme of things, each generation’s eventual embrace of The Decalogue will continue to reveal its timeless and steadfast nature as it carefully examines what it means to be a thinking, feeling human being living in this world.