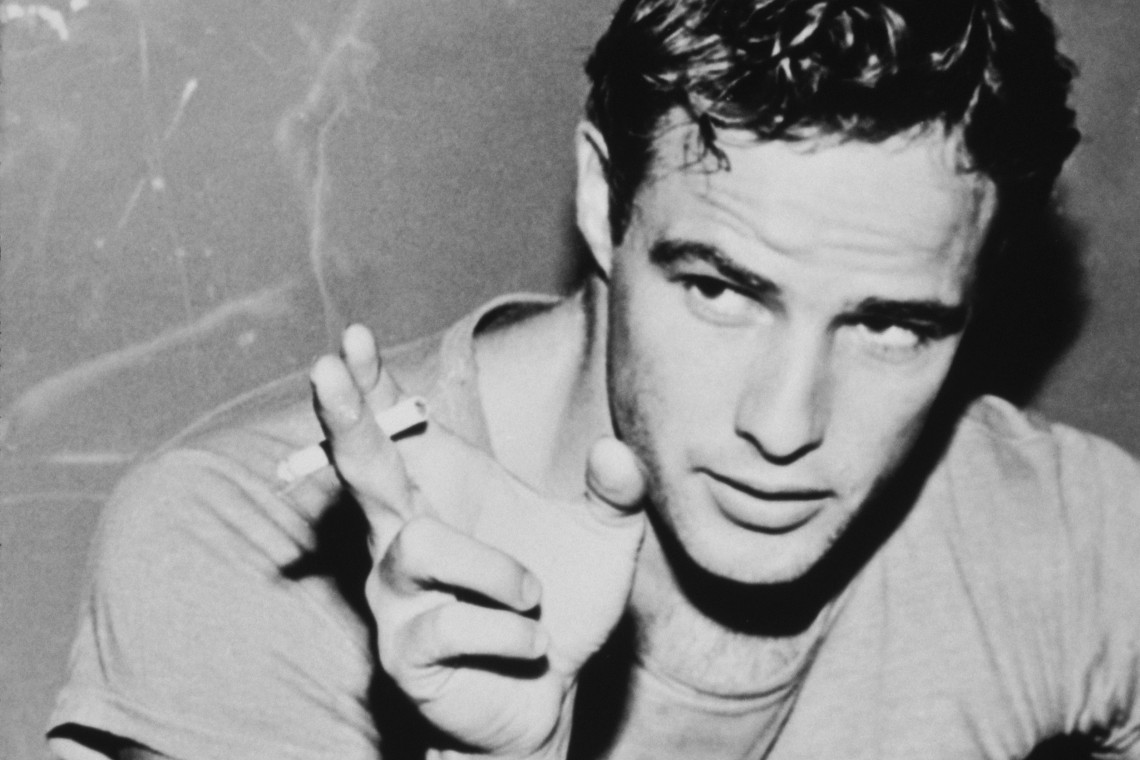

You could thumb through a thesaurus all day and still not find sufficient hyperbole to describe Marlon Brando’s impact on the craft of acting. A prize pupil of Stella Adler, who brought the Stanislavsky Method to America, Brando blew it all up. Overnight, the presentational performance style that had dominated cinema’s first 50 years looked hopelessly dated and quaint. Here was something different and entirely new—seething, electric, alive.

He was also a bit of a kook. Since Brando’s death in 2004, his legacy has been, if not quite marginalized, then let’s just say undervalued by a film culture more interested in his belligerent and often bizarre off-screen antics than the iconic performances he left behind. The “coulda been a contender” line comes up too often, too dismissively, from writers who seem to have forgotten that he’d already won the title, so many times over.

You could almost call Listen to Me Marlon a posthumous autobiography, and it aims to set the record straight, beautifully assembled by director-editor Stevan Riley from archival footage, vintage interviews, and over 300 hours of audiotapes recorded by the legend himself. Much like Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, Riley’s film is the closest we can get to a first-person account from an oft-misinterpreted artist whose work shook the world. Call it Montage of Kurtz.

Indeed, sometimes it’s awfully hard not to think of Martin Sheen and Harrison Ford at the beginning of Apocalypse Now listening to that eerie tape of the renegade Colonel. Brando recorded himself for a lot of reasons: sometimes for posterity, sometimes as a form of hypnosis, and sometimes (I think) because he just liked to hear himself talk. Can’t blame him for that last one; he’s a fascinating cat.

The broad strokes of his biography are presumably familiar to most movie lovers. Marlon Brando grew up in Nebraska, his father an abusive tyrant and his mother “the town drunk.” The early triumphs gave way to a reputation for being difficult and eventual Hollywood exile, only broken when Francis Ford Coppola fought to cast him in The Godfather. The comeback was short-lived, however, After Last Tango in Paris—for my money the most emotionally lacerating performance in film history—sent just about everyone involved off the deep end. Brando’s final years were largely defined by arrogance, obesity and devastating family tragedies.

Listen to Me Marlon allows Brando to narrate the film, telling his own story in his own words. What makes the movie so compelling is just how unguarded and easily wounded he sounds throughout. There’s no slickness or polish here, he comes off as an almost child-like figure too sensitive for shitty, cynical showbiz; sometimes petulant, but mostly just aching. You think of the extraordinary, unexpected tenderness he brought to On The Waterfront‘s palooka Terry Malloy and realize that was pretty much the real thing.

He was also a bit of a scamp. One of the film’s highlights is a series of 1950s publicity interviews in which he playfully seduces every woman with a microphone. These hilarious interactions instructively call to mind his description of his acting philosophy: the struggle to remain forever in the moment and follow wherever it takes you, abandoning your preconceived notions of how a scene should play out. Now if that moment should happen to lead you into an entertainment reporter’s bed, well it’s all part of the process, isn’t it?

But there’s another, much darker interview clip in which Brando has just accepted his Academy Award for On The Waterfront. Backstage at the ceremony, his father is brought out to take some puff-piece questions by his side, instantly poisoning the triumph with passive-aggressive disdain while young Marlon struggles to keep a phony smile frozen on his face. It’s a disturbing snapshot of the abused child, informing the actor’s passionate Civil Rights advocacy and foreshadowing his eventual sabotage of an Oscar ceremony on behalf of Native Americans. The bullied kid spent the rest of his life standing up to bullies.

Even Brando’s late-career “Fuck you, pay me” period is framed by the subject in rebellious terms. (There’s a very funny behind-the-scenes shot of him prancing around as Superman‘s Jor-El while a technician tries to keep cue-cards containing his dialogue out of the shot.) He’d given so much of himself and his art to an ungrateful industry that continuously banished and ridiculed him, it was finally time to just cash their damn checks and go back to Tahiti.

Riley cuts it all together impressionistically, at his best when using edits to suggest how much the actor’s father informed brutish Stanley Kowalski. If sometimes the loose-limbed film threatens to drift into incoherence, that’s also quite fitting for a story told by Brando. Riley’s one egregious misstep is allowing the film’s score to play over some extremely famous movie scenes, cheapening their impact and distracting the hell out of us.

Listen to Me Marlon becomes quite difficult to watch in the final reels, as this once so vital and electrifying figure recedes into self-imposed obscurity, morbidly obese and emotionally destroyed by the tragedies that befell his children. But the film stands as a worthy tribute to a monumental talent, reminding us how much we had, how much was squandered, and how much was lost.

4 thoughts on ““Listen to Me Marlon” Is A Worthy Tribute to Brando”

Pingback: LISTEN TO ME MARLON | SPLICED PERSONALITY

Pingback: BOFCA MID-WEEK ROUNDUP 8/5/2015 | Boston Online Film Critics Association

Pingback: BOFCA REVIEW ROUND-UP: 08/14/2015 | Boston Online Film Critics Association

Pingback: The 50 Best Movies of 2015 | Movie Mezzanine