“He’s a nice guy. But he’s not that nice.” This thought is presented to us early on in Life Itself, Steve James’ loving, peering documentary about the life, times, and passing of Roger Ebert. Over the course of 2 hours, James takes it upon himself to explore this point in earnest; he paints a picture of the late, great critic that is by and large favorable, but contains sufficient warts to steer the film away from the realm of the puff piece. Maybe James’ egalitarian approach isn’t necessary, though. Maybe, in the end, Ebert really was that nice.

Yet Life Itself isn’t content with simply feeding into our cultural reverence for Ebert’s legacy (even though he certainly had his share of detractors). The film does what any good documentary should arguably do – it examines its subject from multiple angles, steering around bias like an iceberg in the hopes of coming to a conclusion that’s objective rather than subjective. But such is the power of Ebert’s amicable magnetism that even at its least flattering, Life Itself feels like fluff. You will not watch this movie and discover a portrait of the man that will upend your opinion of him. You will not gaze upon James’ work in stunned awe over his searing, unflinching brand of cinejournalism.

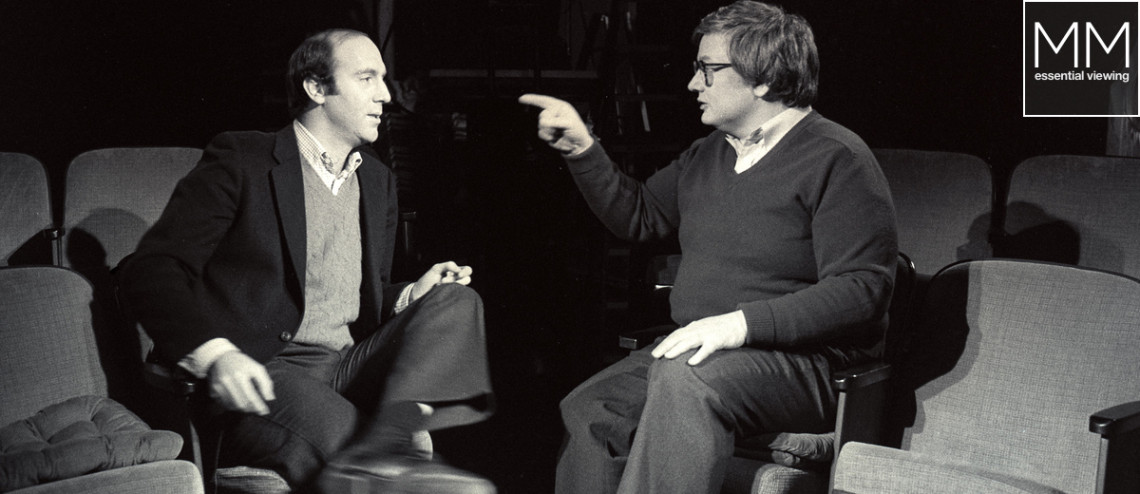

Instead, you will walk away from the film enlightened, misty-eyed, and maybe a bit more learned about the movies. More specifically, you might better understand Ebert’s personal love for the movies in a domino effect of empathy. By understanding what attracted Ebert to cinema, you may, in turn, come to better understand what attracts us all to cinema. James doesn’t want to pull off some investigative hocus pocus and completely alter Ebert’s public image. He wants us all to get to know him better. Every facet of the film is essential to achieving that goal, whether chronicling Ebert’s alcoholism, or his unflattering behind-the-scenes spats with Gene Siskel.

That’s because, ultimately, each of these elements is one fraction of Ebert’s whole. Nobody can hope to understand his best qualities, which were extensive, without a firm, rooted understanding of his worst. In the end, Ebert was just a human being like the rest of us, major differences notwithstanding; most of us can’t claim any credit for helping to sustain the careers of any major filmmaker, much less Martin Scorsese. Nor can we pat ourselves on the back for championing lesser known artists like Ava DuVernay and Ramin Bahrani. Ebert also had a Pulitzer and wrote a screenplay for Russ Meyer. The list goes on.

But Ebert was human. He was loved, respected, honored, despised, usually the former three more than the latter. Life Itself gets that. His humanity is felt so deeply that we’re practically in the room with him as he struggles through painful physical therapy during his long endured bout with cancer. We aren’t watching someone whose opinions on everything from movies, to politics, to video games may have, on occasion, inflamed his readers. We’re watching a person battling for their life. Somehow, James manages to infuse these sequences with a synthesis of heartbreak and uplift.

For James’ part, Life Itself looks handsome. He shoots every sequence with crisp, authoritative clarity. Every image makes a statement and tells a story; he understands how to make the documentary cinematic, something too many of his peers fail to grasp. Most of all, he’s gathered an impressive array of interviewees to add their color to his palette: not only Scorsese, DuVernay, and Bahrani, but Errol Morris, Werner Herzog, and Gregory Nava, Gene Siskel’s wife, Marlene Iglitzen, A.O. Scott, producer Thea Flaum, and, most of all, Chaz Ebert, Roger’s own wife, who regards James’ camera with unbelievable poise and dignity.

Any child of the Internet with a love of cinema has a Roger Ebert story to tell. Some of them are lucky enough to have had personal interaction with him. Most never got that chance, but Ebert left a lasting impression on them regardless. That’s the kind of person Ebert was: someone who handed down his passion from one person to the next, opening up our minds to the possibilities of the medium he loved so dearly. Life Itself – one of 2014’s finest films – captures that gift with boundless warmth, bidding a fond farewell to one of the movies’ most beloved voices.

2 thoughts on ““Life Itself”: Portrait Of A Film Critic”

Pingback: The Great Movies Life: Roger Ebert’s Best Essays | Movie Mezzanine

Pingback: REVIEW: LIFE ITSELF – PORTRAIT OF A FILM CRITIC