2016 marks the 50th anniversary of Kartemquin Films, the august Chicago-based documentary house behind such classics as Hoop Dreams. That an independent film organization—and one that makes the perennial money-losers that are documentaries, at that—has been able to survive so long seems almost miraculous. In surveying the company’s history through research and phone conversations with co-founders Gordon Quinn and Jerry Temaner, as well as current director of communications and distribution Tim Horsburgh, it becomes evident that an octopus-like adaptability was the key. There’s no single form that one can point to as the definitive definition of Kartemquin. Over the decades, the nonprofit’s only constant has been that it’s put out well-made, informative, engaging, and sometimes masterful documentaries.

Like many colleges, the University of Chicago was a hotbed of activism during the 1960s. Quinn, Temaner, and Stan Karter were there at the same time as current senator and Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders (though none of them were friends with him), and footage Temaner captured of a 1963 protest in Englewood made headlines earlier this year when a shot of Sanders being arrested was discovered within it. The trio’s own interest in progressive causes overlapped with their studies in and love of film. Nonfiction films were favored political tools of leftist agitators at the time, and the Documentary Film Group screened such works in dorms and auditoriums, though their interests also included fiction. (Temaner watched alongside a young Philip Glass, who would go on to contribute brief pieces of music for Kartemquin’s Inquiring Nuns and Marco. “I think we paid him two or three hundred dollars for that,” he says.)

At the same time, direct cinema emerged. Directors like the Maysles brothers, D.A. Pennebaker, Richard Leacock, and Jean Rouch (Quinn and Temaner both cite all of them as influences) sought both to capture reality and to get audiences to think about their relationship to what they were watching. “I was, like, ‘Oh that’s what I want to do,’” Quinn recounts. “I wanted to make those films, where you don’t know what the story is when you go into the situation, you follow what happens to people’s lives, and then reflect those stories back into our democratic society.”

Temaner provides further context for the period: “Documentary, with a few exceptions, was what the networks did. It would mostly be a voiceover, while the visual part was usually just there to illustrate what the narrator was talking about. They still do that on news shows today.” People forget that, for nearly half of the time that cinema has existed, the documentary form was utterly dominated by newsreels and otherwise informational and/or educational films. There have been exceptions from the very beginning, and important artistic strides have been made within such work, but there’s hardly another example of an art so long constrained by limited conceptions of what it could be. It’s no wonder that there are still many people today who bristle at any doc which does not conform to the standard of “objectivity” that exists only in their head.

Quinn describes his first collaboration with Temaner and Karter: “Jerry was a graduate student while Stan and I were undergraduates, but we were all in Doc Films. We were looking for a way to learn about film production (there were no classes for it at that time at the University of Chicago). I think it was Temaner who got somebody to give us $5,000 to make a film about the college. It was directed by Vern Zimmerman, who was already an experimental filmmaker and knew more about the craft than we did.” This project paved the way for Kartemquin’s inception a few years later.

The trio’s leftist aspirations are reflected in the company’s name, a pun on Battleship Potemkin formed as a portmanteau of their names (Stan Karter, Jerry Temaner, and Gordon Quinn). In that spirit of progressiveness, Kartemquin’s first endeavor was an attempt to start a conversation about elder care in America. Home for Life (1967) follows two new residents of an old-age home. Though the film earned plaudits from the likes of Roger Ebert and Studs Terkel, it didn’t instigate the societal change the makers were hoping for. “It was used primarily for people to talk about how to make nursing homes better—how to improve the institutional solution,” says Quinn. “We began to understand that if you’re talking about real change in society, you just can’t reflect a problem back onto it. You also have to examine power relationships within it, and help people understand who has power and who doesn’t. That has to be a part of any strategy for making social change.”

Quinn and Temaner used their experiences making Home for Life as the basis of their scholarly article “Cinematic Social Inquiry,” which would later be collected in Paul Hockings’s Principles of Visual Anthropology. Quinn refers to the essay as their manifesto: “There’s a tremendous value in recording society and looking at political struggles, what’s going on in a family, people at work, how education takes place—all these subjects that we were dealing with. We’re not claiming to be objective; we understand that every time you point the camera one way or another, or make an edit, you’re making a statement. The idea would be that people are looking at this film and may see things that we never saw in what we captured. It’s far less mediated than writing an article or something like that.”

Home for Life may not have sparked a revolution in elder care, but it did provide the filmmakers with a calling card. While Stan Karter left the company to pursue his own path, Quinn and Temaner teamed up with a Catholic organization called InterMedia, which was impressed by Home for Life, for their next few projects. “Those were the McLuhan days—you know, ‘The medium is the message,’” Temaner says. “The idea that they had was to use films to stimulate discussion. They came up with study guides, questions that people would ask at church meetings and youth meetings and so on.” Quinn remembers how “they actually wanted us to make, I think, six or seven short…10- to 20-minute films. I would say that we influenced them to make much longer and more in-depth films. We would come to them with suggestions which we thought would resonate with Catholics. Like, in [Jean Rouch’s] Chronicle of a Summer, there’s a famous scene of two women going around Paris and asking people if they’re happy. We were like, ‘How about two nuns?’”

Cutting their teeth on the Catholic commissions helped prepare the Kartemquin team to tackle subjects closer to their own hearts, though they’d have to do so without Temaner. “The last film I worked on was Marco, which was about my wife giving birth,” he explains. “We had the kid and we weren’t making money and blah blah blah. So I went to the University of Illinois at Chicago and taught there for about eight years.” He and Quinn were in the middle of an interview with one Jerry Blumenthal when they got the call that Barbara Temaner was going into labor. Blumenthal ended up being an assistant editor on Marco, and he would go on to join with Quinn as the creative backbone of Kartemquin for more than 40 years, working right up until his death in 2014.

Though Quinn and Blumenthal were at the center of the organization now, the ’70s would see Kartemquin take on a structure like few film companies before or since. Says Quinn: “We were approached by Jennifer Rohrer and Sue Davenport to get involved and help them make The Chicago Maternity Center Story. That was the beginning of the collective. Other people started coming around and sort of congregating around this film company. We had this shared political aim to make films around social justice and change society for the better.” Horsburgh explains how these artists “were given support and mentoring and equipment. They learned skills and worked on each other’s films while producing their own.”

To look at the crew lists of Kartemquin’s work from the ’70s is to observe a fascinating, continual shifting around of the same names. Along with Quinn and Blumenthal, there’s Richard Schmeichen, Alphonse Blumenthal, Sharon Karp, Betsy Martens, Judy Hoffman, Susan Delson, Teena Webb, and more. Karp, for instance, worked in an assisting role on Winnie Wright, Age 11 (1974), as an assistant editor on Viva la Causa (1974), a director of Now We Live in Clifton (1974), a production associate on HSA Strike ’75 (1975), and a cinematographer on What’s Happening at Local 70? (1975).

The company’s output from the time reflects this collectivist spirit. Before this most recent decade, the ’70s marked Kartemquin’s most prolific period, with its energy-pooling model spinning out 14 films over seven years. Most of them were shorts, and many were looks at local social movements, especially what was being done by unions.

There was just one problem. “We never came up with a way for people to make a living,” Quinn says. “Although our core value of skill sharing helped some of them go on to make a living. Sharon Karp is an example. She became an editor and founded her own company, Media Monster. Others went back to things they’ve been doing before the collective—teaching, union organizing, things like that. We weren’t a financial collective, and as people got older and started to take on other responsibilities, they needed to be able to make a steady income.”

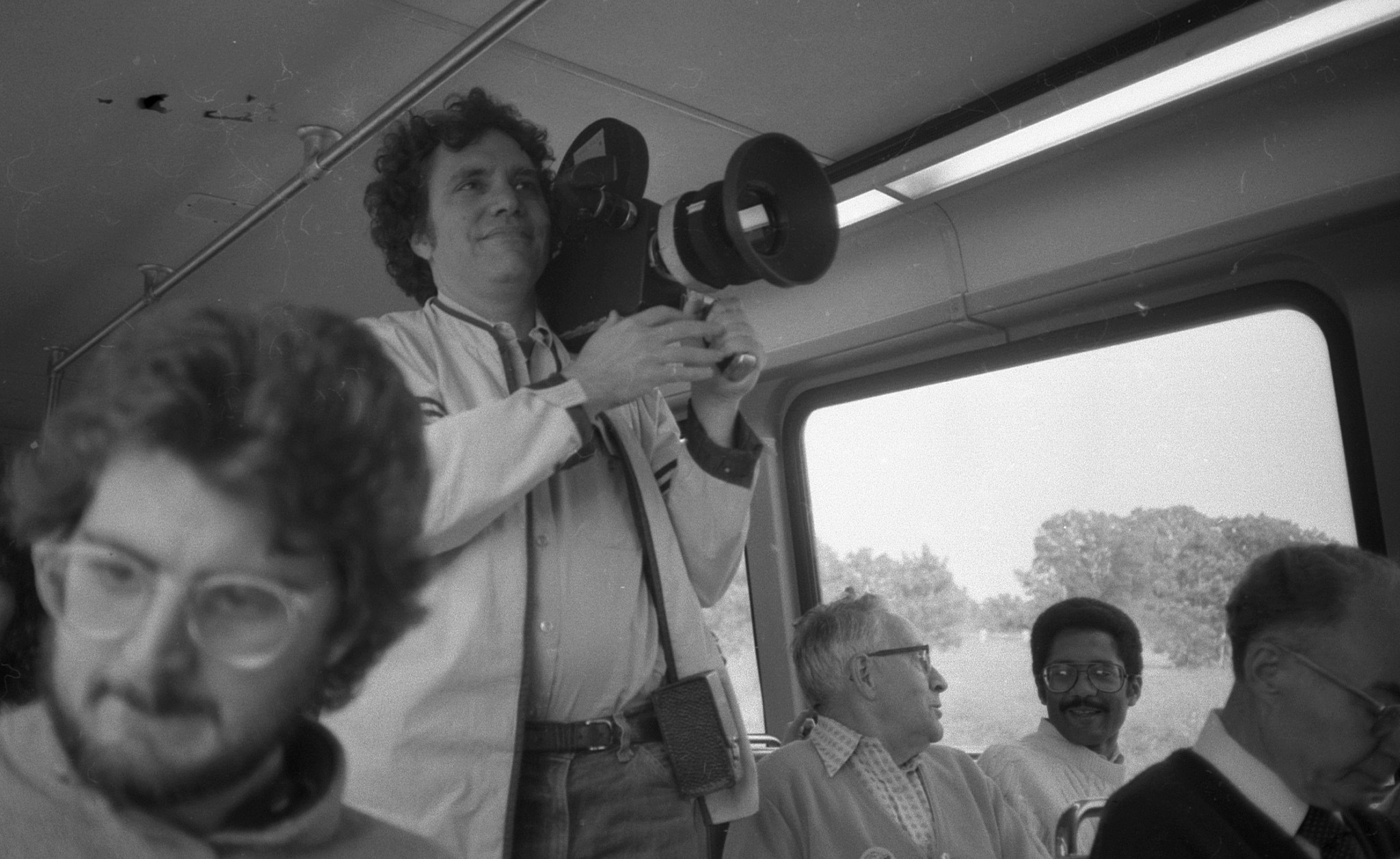

Though the collective’s heyday was over, Kartemquin kept itself afloat going into the ’80s by dividing time between continuing to pursue its members’ passions and doing work-for-hire projects—mainly industrial films. Quinn found it fascinating to sometimes “work for the enemy,” so to speak. “We weren’t the producer or directors in most cases. By and large, we weren’t selling the job. We weren’t the interface with the corporate clients. We were one honing our skills as filmmakers. We were acquiring equipment and the tools of making films from doing this work.…We did a lot of work for McDonald’s, and at one point we were in their headquarters, learning how this big corporation works and makes decisions. Then we would cover the production aspect in the factories where people were making the hamburgers or the French fries or whatever. Jerry and I both had a long interest in work, how people relate to work, and how things actually get made.”

At the same time, though the collective was no longer around, the model that took hold at Kartemquin persisted. While Quinn and Blumenthal shouldered most of the creative heft around this time (though a few old collaborators, mainly Jennifer Rohrer, were present), they still worked to nurture developing talents. Horsburgh talks of how a few in particular entered the fold: “In the mid-’80s, you have Steve James and Frederick Marx showing up with an idea for a half-hour film about a basketball court. They started on their own with a tiny bit of seed money, and they knew they needed help. So they sought out the help of Gordon and Jerry as experts, and then Gordon said, ‘Hey, I know this guy who’s a cameraman who would be perfect for you guys. He’s also crazy about basketball.’ And that was [producer and director of photography] Peter Gilbert. And that’s how our projects often kind of come together.”

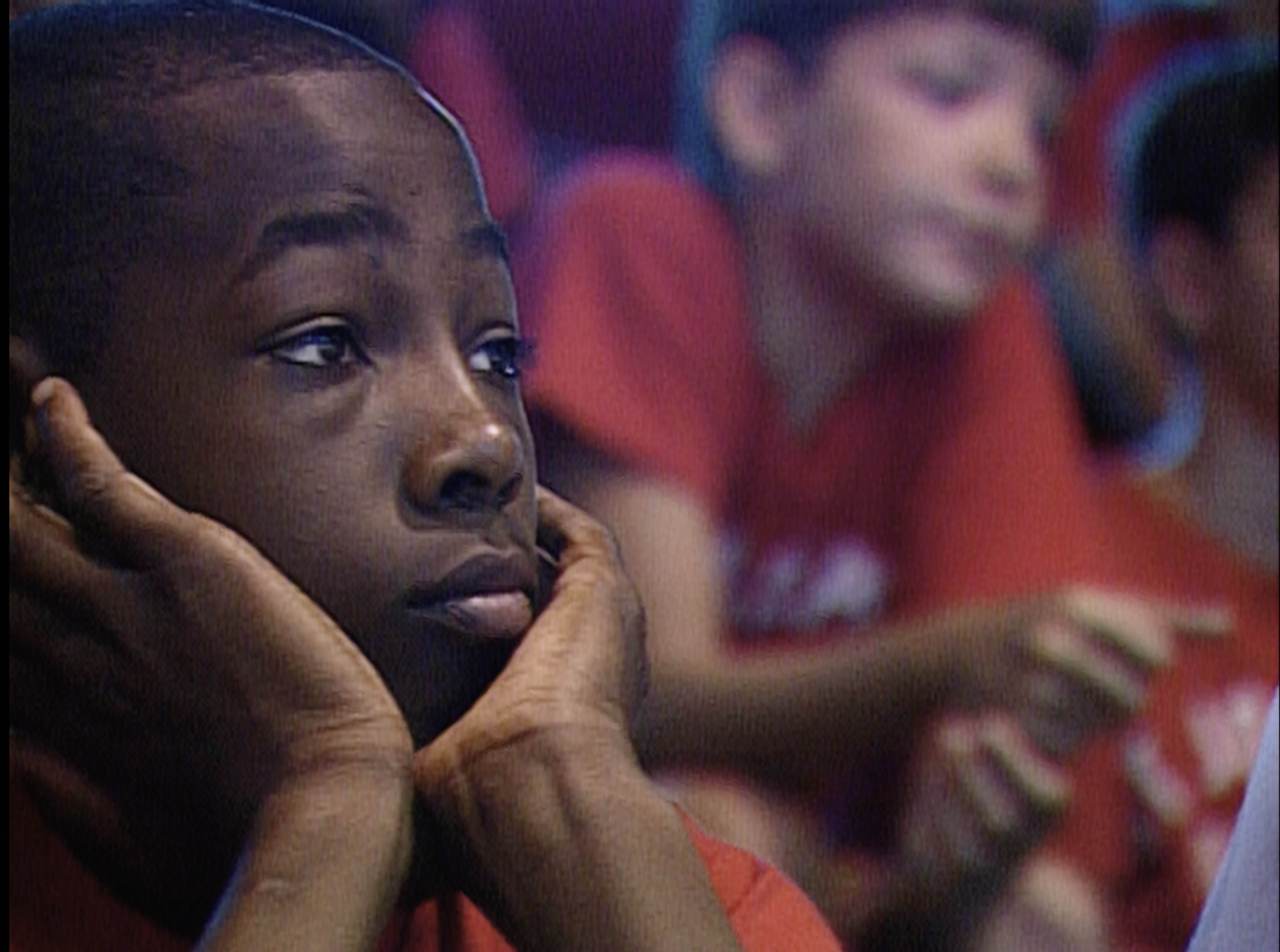

That “half-hour film” led James, Marx, and Gilbert to follow their subjects, a pair of poor African-American boys going to a mostly white high school thanks to their basketball prowess, for over five years. The result was Hoop Dreams (1994), an unprecedented success for the company both financially and critically. Widely considered one of the best documentaries ever made, it’s an epic three-hour survey of its milieu, a scorching examination of race and class in America that hasn’t lost an ounce of its power or relevance. In many ways, the film feels like the perfect culmination of Kartemquin’s philosophy, and a validation of its unusual production process.

Media heat swirled around Hoop Dreams for a time. The Oscars experienced one of its biggest controversies in years over the Academy’s failure to nominate the film for Best Documentary Feature (though notably, it is the only documentary to ever be nominated for Best Editing), to the point where the category’s voting process received an overhaul. In the aftermath, many offers were made to Kartemquin to get a Hoop Dreams 2 going, but they were uninterested in retreading old ground (Steve James’ next documentary was the intimate, rural-based Stevie [2002]). Rather, Quinn, Blumenthal, and co. used their newfound clout to continue to refine their mentorship/mutual feedback/skills exchange model. As the new century dawned and film production became cheaper than ever, this would result in a new influx of talent and a revitalization of their release schedule, which had slowed over the previous two decades.

Horsburgh says that the Kartemquin process is “always about collaboration, whether that’s between a filmmaker and a subject, the partners who we’re working with to release a film, or between us as an organization and an individual filmmaker. And we’re not interested in making something with someone to release it for six months and then never work with that filmmaker again. We’re looking at long-term relationships.”

The company continues to split its resources between supporting its stalwarts like James and Quinn and fostering emerging filmmakers. At the same time that Quinn is working on his new doc ’63 Boycott (researching the company’s archives for the project led him to the now-famous footage of Bernie Sanders’s arrest), Kartemquin has launched an outreach program specifically aimed at minority filmmakers. Making a Murderer creators Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos put their project through the organization’s filmmaking lab five years ago, when they were still figuring out what to do with the wealth of material they had. Kartemquin now thrives, having only recently gotten to the place where it’s financially capable of a more prolific output. Although adaptability has played a role in the nonprofit’s continued survival, to a certain extent, they were ahead of the curve when it came to resource-sharing and skill-swapping, and DIY filmmaking culture has only recently been able to catch up, hence allowing them to flourish.

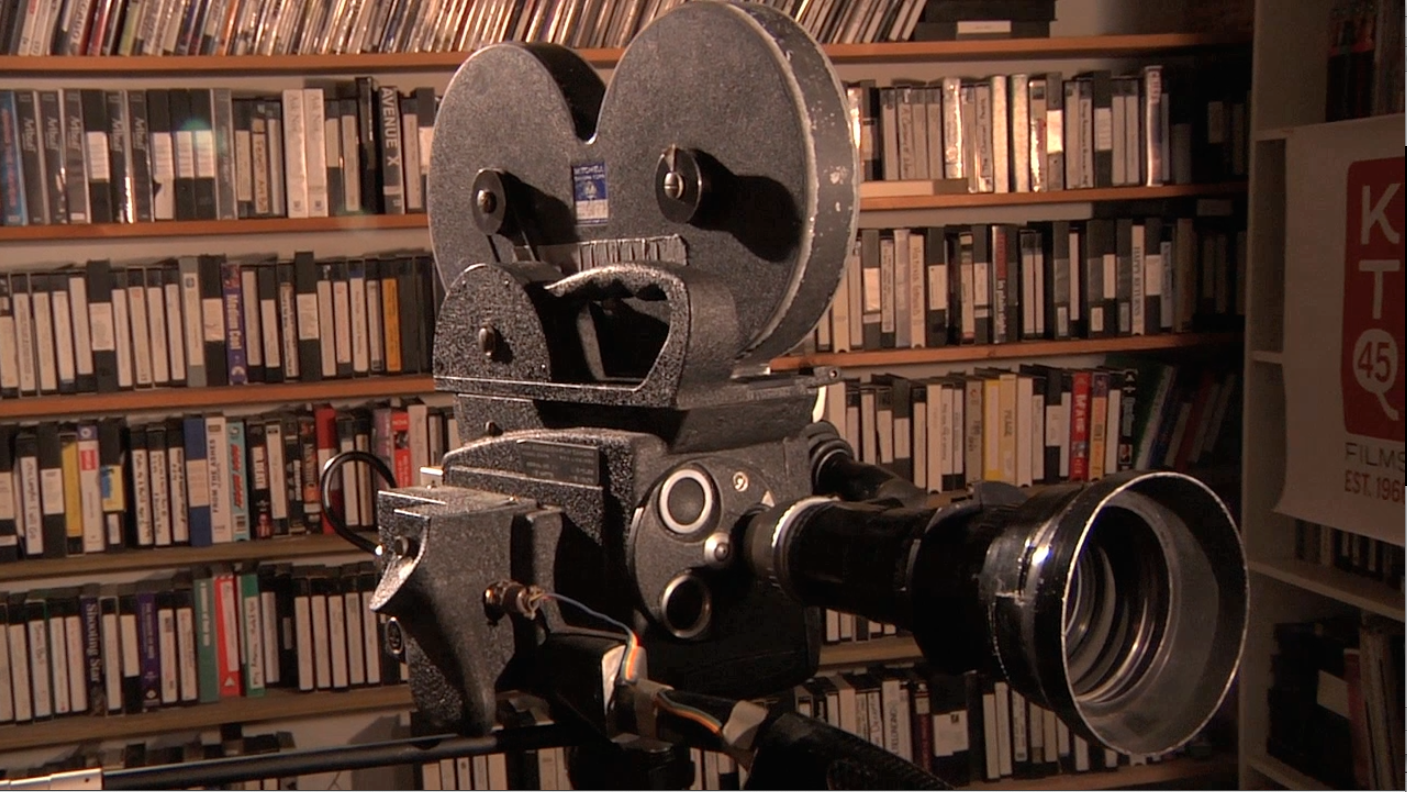

When I ask Quinn what’s changed on the documentary scene in his six decades as a filmmaker, there’s a brief beat. “I’m sitting in my office looking at the camera that I used in the ’60s. The interns found it in storage and asked what it was, this odd-looking home-built thing. When I pick it up, it’s like, ‘God, how did I ever shoot with this. It’s so heavy.’” By now, the ease with which anyone can access the tools of the trade is a codified talking point in discussions around filmmaking in general and documentary production in particular. The digital age has flooded American culture with docs since the late-’90s/early-’00s. But Quinn is skeptical over whether the overall level of difficulty has truly been lowered. “We’re still trying to tell stories in depth about what happens in the world and people’s lives. Fundraising is still really tough, too. Even though there are more sources and more places you can go for funding, there are also a lot more people competing for it. And telling a really honest story is still a struggle.”

2 thoughts on “Telling An Honest Story: Kartemquin Films at 50”

Pingback: Doc Memo: An Honest Look at Kartemquin Films, Recap on VR at Hot Docs 2016 | Documentary News | POV Blog | PBS

Pingback: 2016 In Review: March - June