More than any filmmaker in the Hollywood studio system, M. Night Shyamalan’s cinema is exposed and vulnerable: his sincerity construed as naivety, his faith as illusory, his worldview as archaic. Within his altruistic belief system, love overrides traditional logic, and faith overrules deduction: How could a cripple stage multiple terrorist attacks? How could a blind woman navigate a forest on her own? How could gusts of wind cause mass suicide? “The world moves for love,” Edward Walker says near the end of The Village—an affirmation of a priest’s faith (Signs), an overarching narrative that defines a handyman’s purpose (Lady in the Water), and a burgeoning father-son bond that overcomes natural threats (After Earth). But in his latest film, Split, and his previous one, The Visit—both of which have been dubiously narrativized as returns to form—Shyamalan’s cinema turns inward, toward macabre introspection. The following conversation reflects how Shyamalan reconsiders his own philosophy and theology with Split’s intertextual elements.

*Spoilers ahead*

Josh Hamm: You’re the biggest Shyamalan fan I know. What was going through your head when Split was announced? Were you excited about his return to a familiar genre? Up until a year ago, I considered myself a moderate fan of his, but as I’ve been revisiting his filmography, I’m realizing how precisely Shyamalan’s emotional pitch resonates with me. Even so, I found myself initially disinterested in Split because I didn’t see him as a filmmaker defined by thrillers, but as a dramatist, and I wasn’t sure how the premise of a man with 23 personalities would measure up.

Josh Cabrita: Because the film is enclosed in a single space and appeared fitted to marketable expectations, I anticipated something like The Visit or After Earth, which adapt familiar modes and tropes to Shyamalan’s form and tone without doing anything too radical. Instead, what appeared to be an overly familiar set-up lends itself to one of Shyamalan’s most ambitious works, transforming a story about three teenage girls abducted by a serial killer with Dissociative Identity Disorder into a form of self-criticism. His previous two films seemed to indicate diminishing ambition. I was wrong.

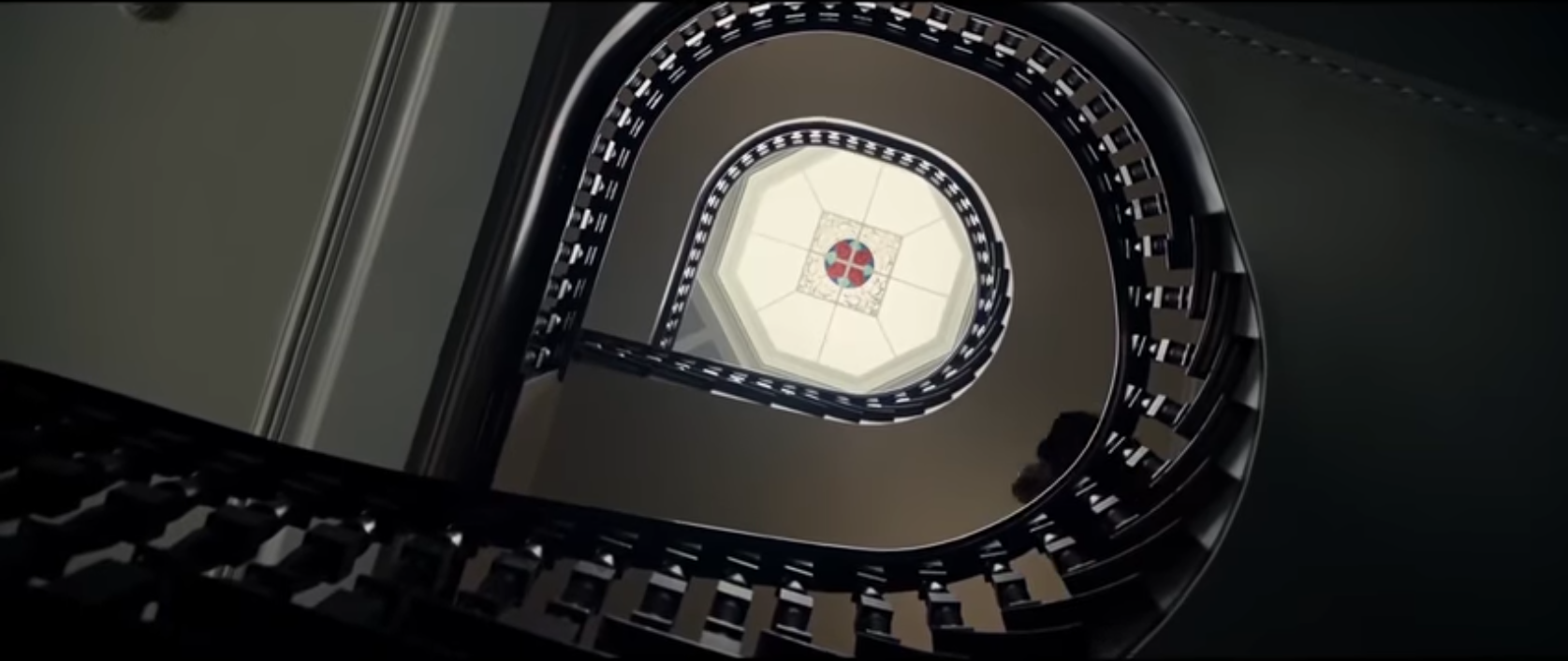

JH: I’ll cop to the same sentiment. Shyamalan’s films subvert their genre, but never place their trust only in his technical skill. That’s why it’s often frustrating to see him critiqued for relying on “twists” and his striking images. Shyamalan has always had exquisite control over his visuals, but here he takes full advantage of DP Mike Gioulakis and films claustrophobic spaces in ways that open them up and use negative space to its full potential: an arresting opening shot that immediately establishes the looming threat unseen while the focus provides characterization (the camera functions as both POV of Kevin [James McAvoy] and establishes the division between Casey Cook [Anya Taylor-Joy] and the other girls); how they open up confined space with childhood flashbacks, interrupting the formal structure of the film in favor of Shyamalan’s classicism from films past; compositions ripped out of his old films, keeping the frame while updating the upholstery. Shyamalan layers his images upon images, allowing each frame to hold much more information than we initially realize. It’s counterproductive to reduce any filmmaker to one or two characteristics, of course, especially mere formalism, and because Shyamalan constructs his films with so many intricately moving parts, focusing on one is nearly impossible.

JC: And Split is a culmination of much more than just Shyamalan’s formal prowess. It’s also a recapitulation of themes he’s been exploring since his debut, Praying with Anger. His films are stories about stories—comic-book ideology in Unbreakable, Christianity in Signs, post-9/11 fear in The Happening, etc. In all of these films, the reformation of family coincides with a protagonist’s reclamation of the meta-narrative: When David Dunn in Unbreakable finds out he’s the hero, he reconciles with his wife and child; when Graham Hess in Signs comes to terms with his wife’s death, he goes back to his faith; when Elliott, Alma and Jess form a surrogate family, the “happening” abruptly comes to an end. Love binds these stories and families, controlling everything in its path. Split coils around Shyamalan’s oeuvre and re-imagines his stories, but this time love, or its counterfeit variant, consumes rather than consummates.

JH: Exactly! We’ve seen love as the focus of his filmography. Part of why Split is so chilling is how untethered it is by any sense of love’s presence. Whereas Shyamalan is often concerned about reconciling families and societies, here it is both family and society where evil’s head emerges. Even if his characters in his previous films cannot help but fall short in their patchwork attempts to restore their broken families and loves, they are usually able to do so once they restore their sense of purpose and place in the world—this is especially apparent in Unbreakable, Signs, and The Village. In Split, the only figure who receives a sense of purpose, almost by divine revelation, is The Beast, Kevin’s emerging 24th personality. The only love that succeeds is the self-flattering idolatry of a creature consumed by itself. The two villainous personalities, Dennis and Miss Patricia, choose to worship power and choose the love of The Beast over the offer of adoptive family from Dr. Fletcher (Betty Buckley) and the reconciliation of the rest of Kevin’s personalities, manipulating Hedwig into following them with lures of another kind of love. Family is either broken (as seen by the death of Casey’s father and the abuse of her uncle), or rejected in favor of a more sinister shadow of what it should be.

JC: Family is not only dismembered like in Shyamalan’s other films but perverted; it doesn’t bear the brunt of trauma but is, in fact, the very cause of it. Just as the flashback structure in After Earth and Signs revealed the cause of familial dysfunction, the same device is used here, but instead of having tragedies caused from outside the family (a car crash, an Ursa attack), the trauma comes from within.

JH: You’re tapping into why Split is such a heartbreaking and horrifying film. Casey doesn’t escape from her abuse: First, The Beast lets her go because of her scars and what he calls the purity of her brokenness, but then the real horror of the film sets in. Now safe in the back of a police car, an officer approaches Casey. “Your uncle’s here,” she says with a gentle hope in her voice. Casey responds with a firm glance explaining all: the realization that she is merely exchanging one abuser for another, a physical basement for a mental prison, from an identifiable form of victimhood to one that is further underground. Whereas Kevin’s personalities are easily distinguishable, her uncle’s abusive nature is much more insidious, hiding under a mask of paternal care and a gregarious persona.

JC: But, of course, the film doesn’t stop there. The first ending fills in the plot (revealing Kevin’s lair as a zoo’s basement), while the second fills in its ideas: Kevin’s dominant personalities (Miss Patricia, Hedwig and Dennis), empowered by The Beast, discuss their newfound abilities—the main theme from Unbreakable bellowing over Kevin’s chorus of voices. Shyamalan’s endings reframe our consciousness and re-contextualizes the nature of the film itself: The Village from folk tale to a modern fable, The Sixth Sense from domestic drama to ghost story, Unbreakable from family drama to superhero movie. In all cases, these stories are revealed to be about stories. Split’s inversion of Unbreakable is simple: Kevin places the main theme music associated with David Dunn on himself, unveiling a super-villain’s origin story, not a super-hero’s. What intrigues me is not the tenuous connections between Split and Unbreakable but the meaning behind the act itself—what happens when another film’s images and meanings are imposed upon another?

JH: He is constantly pitting them against each other. We see the physicality of the hero vs. the mental prowess of the villain in Unbreakable, only for Shyamalan to flip the script in Split by allowing Casey to survive by playing mind games with Hedwig and thinking one step ahead against the savage strength of The Beast. And in both films, the villain is portrayed with genuine empathy; it’s both incredibly humanizing and yet unsettling on a primal level. There’s an uncanny terror that forces the audience to identify with the victim and the attacker, which is elevated by the spiritual connotations hovering over the film. Shyamalan works in religious symbolism and ideas, either overtly—as in Signs’ struggles with theodicy and in the cultural backdrop of The Village, all the more curious that a makeshift society thought they needed the structure of religion to reinforce their isolation—or more subtly, such as the fantastical airs of Lady in the Water and the nihilistic bent of The Happening. I think he’s at his most intriguing when his cinema grapples with this language of the supernatural.

JC: You’re right, but his spirituality, an amalgamation of Christianity and Hinduism, Western and Eastern philosophy, is extremely difficult to define. Though the religiosity is more covert in Split than it was in, say, Signs, it underlines the sincerity of his approach and the reversal of his traditional perspective. While purity is associated with chastity and innocence, the opposite is true in Split. As the girls are separated from each other and asked to take off another layer of clothing (the inverse of “purity”), it is this undressing that leads Kevin to notice Casey’s wounds—“Your heart is pure, rejoice!” The Beast exclaims that “the broken are the more evolved,” which is reminiscent of The Beatitudes from The Sermon on the Mount:

“Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven”

“Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted.”

“Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.”

JH: It’s in the delivery of McAvoy’s lines as well: He’s caught up in a zealous fervor, filling the screen with his bulging eyes and blood-soaked teeth as he gleefully cries out “rejoice!” It has the unsettling feeling of divine epiphany, as if he’s about to break out into a hymn in worship of brokenness. It neatly encapsulates the paradoxical logic of Christianity in the Beatitudes, but adds another turn of the screw. Instead of “Blessed are those who are persecuted because they shall inherit the kingdom of heaven,” essentially that they will be loved greater in response to their suffering, The Beast’s phrase twists the original sentiment into a paean to pain. He claims the broken should rejoice not because they will be embraced by divine love, but because through their suffering they can achieve inhuman strength and become like gods among men. This theological subversion continues as The Beast is recovering from his shotgun wounds, marveling at his own indestructibility. It calls to mind this passage: “One of the heads of the beast seemed to have had a fatal wound, but the fatal wound had been healed. The whole world was filled with wonder and followed the beast. People… worshiped the beast and asked, ‘Who is like the beast? Who can wage war against it?’” (Revelation 13:3-4). This is the end goal of Kevin’s bestial personality: to actualize himself as a higher form of humanity, and to be recognized and feared because of it. The desire for recognition of existence, which motivates Dennis and Miss Patricia to seek out The Beast, morphs into a Faustian bid for power once they’re witness to his abilities, granting themselves superhuman power in exchange for the core of their humanity.

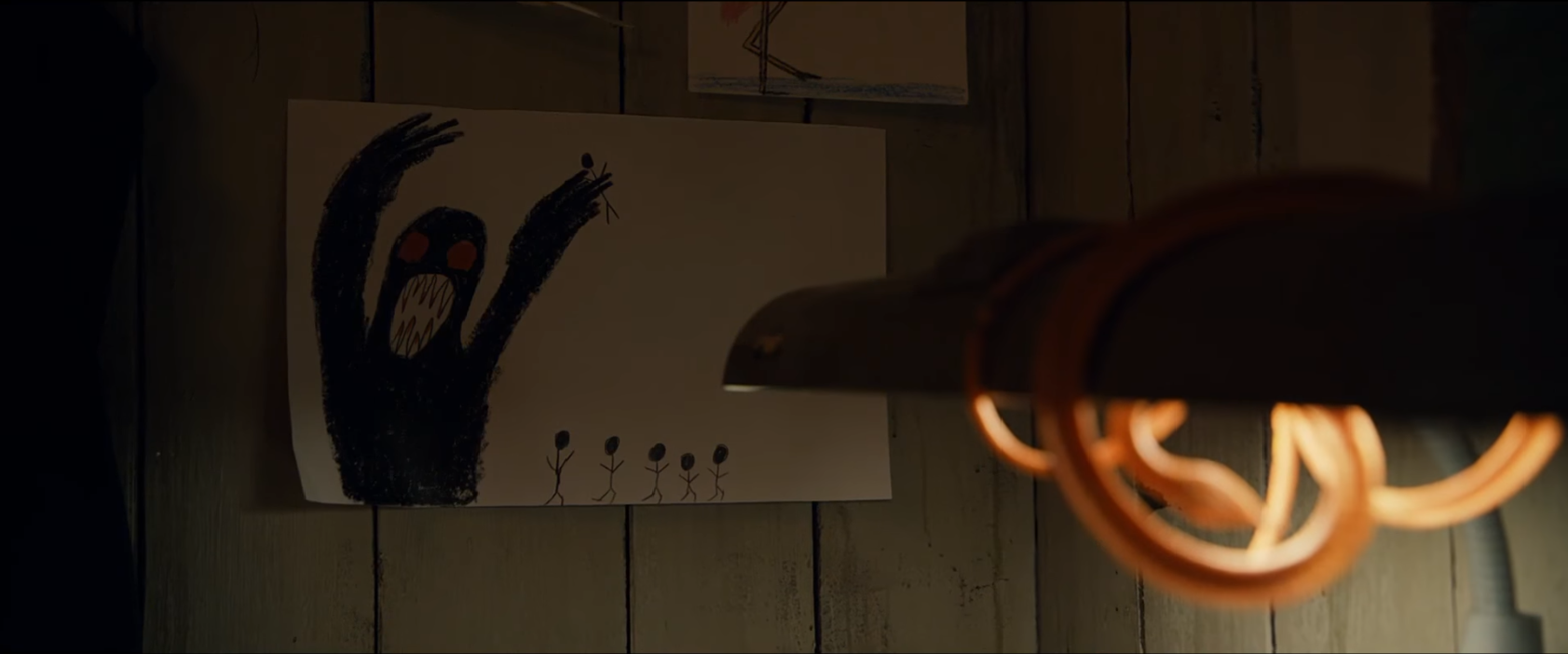

JC: And formally, Shyamalan undercuts Kevin’s self-love and lust for power. The irony of the The Beast finally emerging “into the light” and escaping the confines of the basement is that Shyamalan still frames him as a prisoner. As he’s basking in his strength, prying open the bars of Casey’s cage, the camera places him within the cell, as if he’s the one trying to escape. Kevin’s make-shift prison is where Shyamalan’s stories go to die. Morgan is in awe when the baby monitor catches the alien frequency in Signs; when Casey tricks Hedwig into giving her the walkie-talkie, the person on the other side evades her cry for help. The elders of the village seek to preserve innocence when they bar themselves from the outside world; Kevin’s cages (the zoo’s outside gate, the doors inside the basement, the individual animal cells) harm those stuck inside. The fairy-tale imagery that opens Lady in the Water ultimately provides Cleveland Heep with meaning and purpose; Hedwig’s drawings of The Beast are objects of self-worship. If the world moves for love, Split demonstrates what happens when that love is absent, corrupting families, deranging theologies and unravelling the stories that tie these things together.

***

Josh Hamm is a freelance writer and programmer from Vancouver. He has written for The Film Stage, CutPrintFilm, and PopOptiq.

Josh Cabrita is a freelance writer and programmer from Vancouver. His work has appeared in MUBI Notebook, Cinema Scope and the Georgia Straight.