Blade Runner is a reminder that some films deserve a second chance. At its initial release the film was a flop. To be fair, the theatrical cut of the film contained an unnecessary Harrison Ford voiceover as well as an ending that felt a bit too conventional for a film as bold as Blade Runner. However, as Ridley Scott began to work on a cut closer to his original vision and the film began to be seen by more and more people, it became considered one of the pinnacles of science fiction in film.

Blade Runner is ambitious. Even today there’s something about the scope and detail of the world that comes across as maddening and innovative. And the problem with ambitious creations is that not everyone is going to get it. While other sci-fi films from the same year (The Thing, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Kahn and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial) offered film audiences heavy doses of suspense, action and adventure, Blade Runner is a film where characters espouse philosophical treatises while behaving strangely.

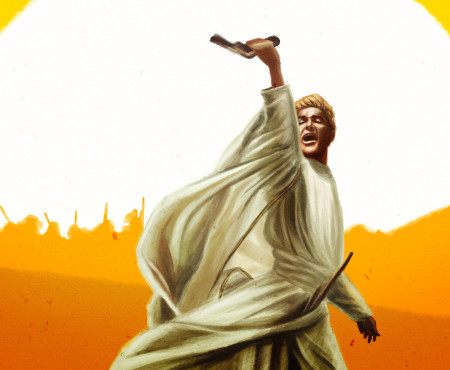

Even to this day I’m astounded by how many people love this film given the fever-pitched insanity of the final act. Rutger Hauer howls like a wolf, taunts Harrison Ford in singsong, drives a nail through his hand and then gives one of the most iconic (and, if we’re honest, indulgent) monologues in cinema. Even while I giddily enjoy the last few moments of the film, I sometime ask myself how so many people can end up loving something that is this esoteric and bizarre.

I think part of the affection has to do with the film’s expectations being reformulated. At the time, people expected Blade Runner to be an action-adventure sci-fi film. That’s how it was marketed. It starred the guy who charmed the world a year ago as Indiana Jones, and four year before that as Han Solo. However, once the film was out, people began to realize this was a different brand of sci-fi, this was science fiction at its most philosophical and arcane. With those redirected expectations, the film began to take on a life of its own, and subsequently audiences were able to gravitate to Blade Runner as a piece of art more about ideas and less about coherent plots, realistic characters and satisfactory resolutions.

In 1991, Ridley Scott released his approved Director’s Cut of the film. This version cut the voice-overs, put in the unicorn scene (try imagining the film without that element), and gave a more ambiguous ending. The result was a more nuanced cut that felt better in-tune with the bold vision of the world, stories and ideas of the film. The Final Cut most people watch today is The Director’s Cut with a few continuity and digital fixes.

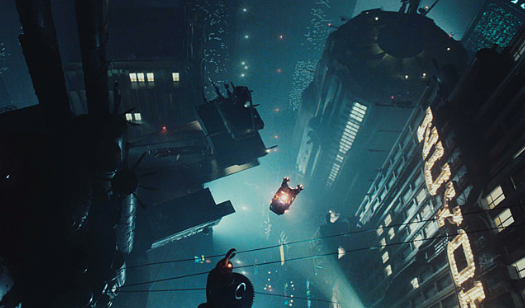

The film is also a visual feast. The dark cityscapes, the liberal use of blue lights and the rundown ground level slums have become ingrained as the look of a more downtrodden future that has emerged in countless science fiction stories since the film’s release. Composition, practical effects and set design also are mind-bogglingly meticulous, ethereal and alluring. It’s a film that demands a big screen viewing.

But isn’t Blade Runner one of the rare exceptions? I would remind you that we’ve recently had a similar reevaluation of another infamous box office flop from the ‘80s: Heaven’s Gate. A digital restoration of the film, wider access to a director approved cut of the film and distance from the picture’s clash with its political zeitgeist at release has given us a space to reevaluate Heaven’s Gate as well as expose it to a new generation that previously avoided it because of its reputation.

Blade Runner’s placement on this list of the ten best films of the ‘80s has two important lessons to teach us. The first is that we should recognize that some films of ambition deserve reevaluation. As much as I love Southland Tales, I doubt it will be hailed a classic in 20 years, but I’m sure there will be a few films with mixed reception from our time that will be given classic status in a few decades. When that time comes I ask that we give those films a fair second chance instead of falling back onto the cries of derision that we might have given at the film’s release.

The second lesson is that the critical consensus of what films are best is an ever-evolving process. We continue to squabble over which films are worthy and unworthy. And, as we gain — as well as lose — valued critical voices, that consensus is going to change. Let’s not see this list as something definitive, but as a marker of a place and time among a group of particular voices. In a year, polling the same people, there would probably be a different list, and that is an exciting and adventurous prospect because it reminds us that some conversations are worth continually having not because the subjects change, but because we change.

9 thoughts on “History of Film: Ridley Scott’s ‘Blade Runner’”

So far, I’ve seen the original theatrical cut and the 1992 director’s cut as I prefer the latter as I’m usually not fond of voice-overs (unless it’s in a Terrence Malick film) as I think it’s one of the great sci-fi films ever made.

Good narration is hard to find in a film. Too easy to use it as a writing crutch or, even worse, fill a film with an abundance of extraneous information.

What do you make of Goodfellas’ use of narration? I’ve always been curious what the critical consensus of its use was….I’m not sure whether I think Scorsese went a tad overboard with it or if it really is warranted.

Not a big fan of that film in part because the narration was overused. I much prefer Casino.

Hey man, love the article but there are a couple of blatant spelling/grammar issues that really bother an obsessive-compulsive asshole like me. Ex: “a film where CHARACTER espouse philosophical TREATIES,” “charmed the world a year ago as INDIAN Jones,” etc.

Thanks for pointing these out to us!

First time I saw this was late night TV about 15 years ago, catching the middle of the film. It was the original release but it still captured me. The dark, glistening visuals, mysterious ambiance, electronic score…it really put me into their world and I loved it. Excellent point that this film is less about a conventional narrative and characters, but a brave effort into something new. From Alien to this, Ridley seems to have taken that same dark, neo noir ambiance and went somewhere darker with Blade Runner. The perfect film on a dark, rainy night with a whiskey in hand.

It certainly evokes a particular mood whenever you think about the film. That might be one of the film’s greatest accomplishments.

Some mention of the basis of this film being Philp K Dick’s “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” might be appropriate given the author’s focus on the content of this film being “bizarre and esoteric” and calling it “a piece of art more about ideas”.

just sayin’

This is not to take one iota away from Ridley Scott and everyone else who crafted this imaginative futurescape.