All of them. Forget all the other movies ever made. David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia is the reason we go to the cinema. All the great works of art take us somewhere; this movie is one of the greatest objects in the greatest of crafts. Every time we face a screen, to watch television, to watch a picture, we hope to recapture what this film gives us. Choose blasphemy by screening the movie on a small cell phone and we will see a fantastic story about a transforming man. Watch the film on the largest screen we can find — with a corresponding sound system — and we will transport to a world of excitement, mystery, humor and drama. Every frame, every movement, every note in this film is a thing of ambition and beauty. Western Cinema eventually shifted its epics to CGI worlds of space, superheroes, and elves. Otherwise, the only other great epics after this movie were about Italian mobsters, cult leaders hiding in Vietnam, Chinese emperors, and African American civil rights leaders.

T. E. Lawrence is a precocious British military officer whose soft disposition, bright blue eyes and longish hair offends his superiors before he opens his mouth. Meaning, he rubs against everyone, but cannot help it. On assignment, he heads to the scalding Arabian desert on a series of quests, first to find an ally in Prince Faisal to unite the tribes, then to (modern) Jordan, Jerusalem, and Syria to lead them against the Turks, eventually to take on the dominant British themselves, before giving up and going home.

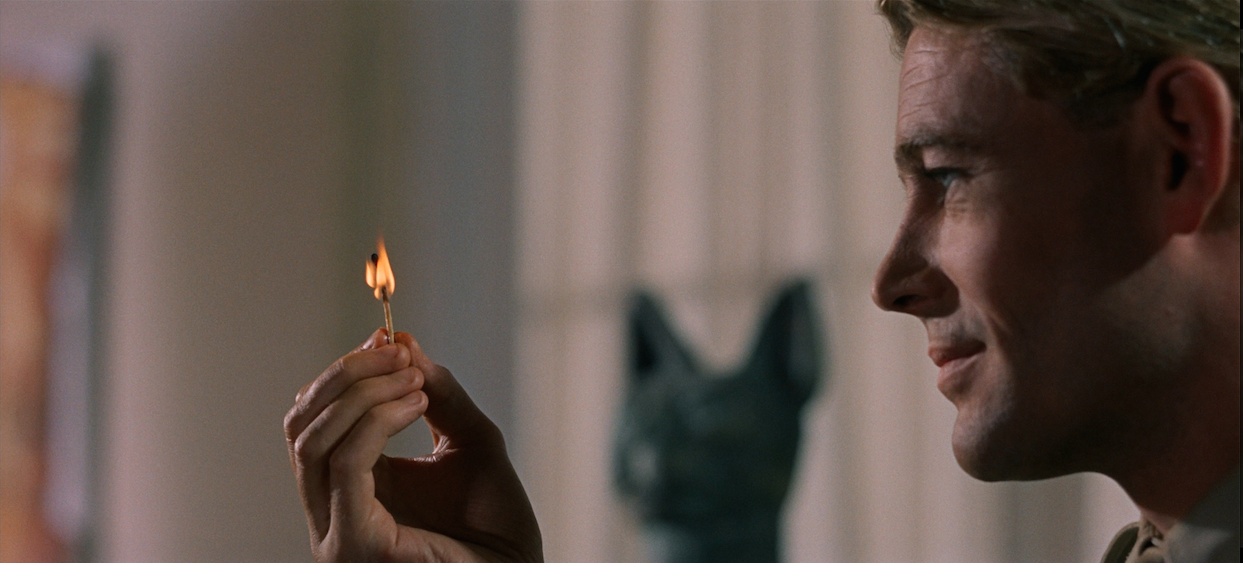

At the same time, this film is two parts, about the “sword with two edges” that mark this complicated man. In the first half, we watch the making of the legend. As officers walk out of his funeral, they wonder about the man they just honored. Intimate with none, distant from all, he seemed to them clear in his principles and purpose. But, he never appeared settled within himself. Often, our greatest mythologies are about men who cannot find their place in the world, so they change the world to conform to them. Meaning, they are not able to not be themselves. As they chart their own way, they carry the world and our admiration along for the ride. Or so they try.

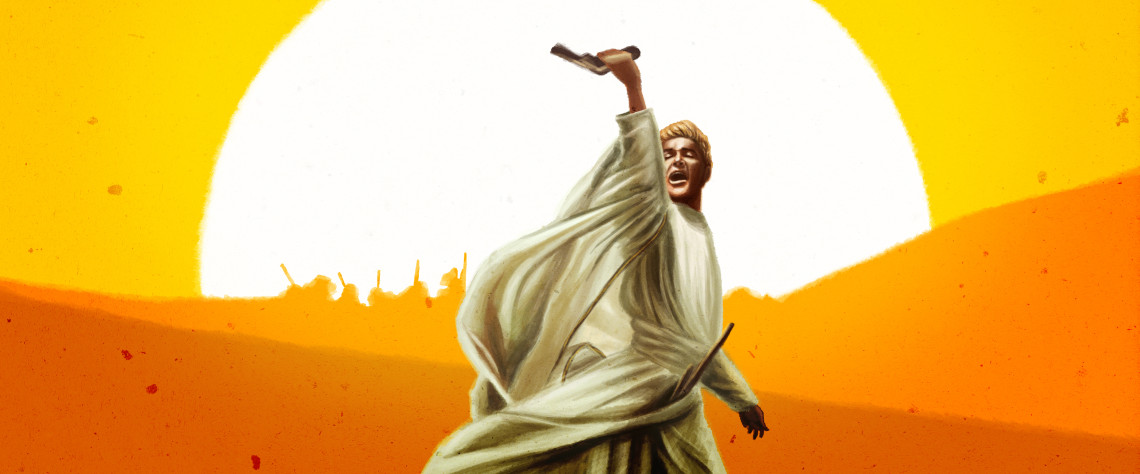

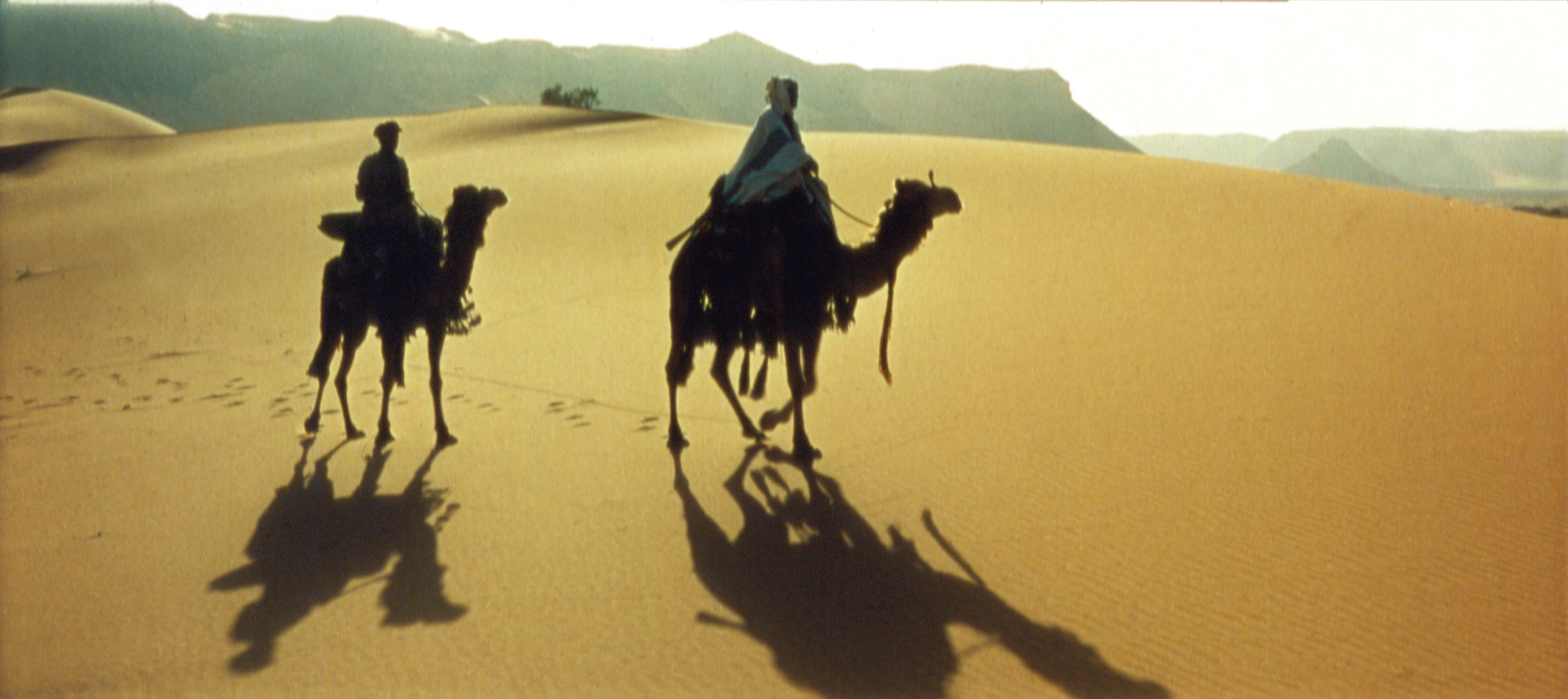

In the second part, he is a Robin Hood in the desert riding his camel as cinema’s original White Savior. The young prodigy prior to the film’s intermission was full of frowns and argument. This man, however, remains clad in the brightest gold trimmed white robes, and claims after getting shot, that “they can only kill me with a golden bullet.” Once a liberator, he starts leading bloody raids. Once, he was the hero for the Arabs living as a native among the noble savages, but eventually he becomes the Messiah incarnate, believing his own hype. Such megalomania, however, has its limits, because when we try to change the world, we begin with frustration, and end with failure. As his spirits come crashing back to earth, his robes get dusty and dirty. So, it is the story of a man not in the quest for military conquest or political glory, but in the exhausting search for his own destiny. He condemned the Arabs’ belief in predestination as cold and hopeless, yet he lived and died as a man raging at full speed to find what was written for him, even if he had to kill hundreds in the process.

Speaking of the White Saviors of Hollywood cinema, many will recognize its obvious influences on such films as Avatar and Dances with Wolves. To be fair, as frequently as the film praises his endeavors leading the Arabs, it also critiques it, commenting that a British foreigner came in and created a mess of the Arabs. But, that recurring thread of the Caucasian elite helping the vulnerable persons of color streams through such modern films as Elysium, The Blind Side, and Django Unchained. Even 12 Years a Slave finds its White Savior in Brad Pitt. But even then, these were all, to varying degrees, emotionally successful films.

Moving beyond the cinematic wonder and through the fourth wall, this film is a mixed message. Speaking of race in this film, the initial problem, is that this formula is so common, that we do not notice it. The British accent gives us a sense of authenticity and dignity. The British savior, however, seems like something normal. The deeper problem, however, is that persons of color internalize these sentiments in various forms of inferiority and self-hate. The whole of Bollywood — the world’s largest film industry — is a frequent exercise in White supremacy by people of color.

Speaking of history, it chronicles the British industrial experiment that transformed Egypt and India, but failed in Arabia. Unintentionally, it also marks a major historical moment in the development of Saudi Arabia, it’s literalist oil-funded approach to Islam and the troubling offshoots. Much of what is happening in the world today, especially in regions America holds interests, was established primarily by the British during their colonial era. The dilemma of Israel-Palestine. The Saudi nation state. The Suez Canal, of major contention during the Egyptian revolution. All were established by the British (with some French involvement).

Further, the film celebrates the dominance of industrialization and modernity over the fatalist pieties of the pre-modern tribal world, and the inability of such desert dwellers to progress. The Enlightenment era of Europe shed itself of Christianity in favor of Empirical Philosophy, and itself was overtaken by the Scientism of Modernity and military advancements that left the Ottomans trailing after them. But, the Arabs were — according to the film — unable to progress because they were stifled by ancient religion and culture; that is exactly the way we picture them today. That myth we hold about the Saudis is a Hollywood creation. Meaning, it celebrates the same colonization that it critiques, asserting that the Arabs are not civilized because they are not civilizable.

The one Arab who envisions transformation is the elegant Prince Faisal, himself exposed to the world past the wind covered sandhills. The rest of the Arabs from start to finish are simple minded connivers, unable to see beyond chances to loot. In depicting the Arabs, it takes its cues from Thief of Bagdad (1940), where Arabs are swarthy fighters, always ready to draw weapons, invoke the Divine, and speak in proverbs.

Further, the Ottomans themselves here are mere Turks, modeled after the Nazis of 1950s war movies. The Arabs in the film take credit for the glories of Muslim Spain, overlooking the six centuries of Ottoman rule in between and the civilizational, cultural, economic, and artistic contributions to the world. Instead, they are the sick man of Europe. Like the Nazis, they have embraced the dark sides of modernity: weaponry, brutality and conformity. Those stereotypes against the Turks soon morph into notions about the savagery of Turkish prisons.

The British, however, are the usual quiet tea drinkers, whose tempers are even subdued. These are not the Imperialists who split up the world, exploited nations through treachery and the distribution of narcotics. No, these are men in suits. Men (because I do not remember a single woman in the film), who think big without any thought about their endeavors except in their roles as the masters of destiny.

All in all, this is such a magnificent film about such an interesting man. It is the high point of Western Cinema, and perhaps all cinema. It is also a cultural artifact, forming so many of our contemporary world views. Nevertheless, in the half century since its release, it is not the movies that have gotten small, it is not the budgets. Rather, what have gotten small are the aspirations for cinematic majesty that this film reaches.

One thought on “History of Film: “Lawrence of Arabia””

I’ve often been fascinated that, as you point out, Lean’s magnificent epic, so empathetic to human foibles and failures on both the grand and intimate scale, contains not one female character and only a single female image – the hand of one of Prince Faisal’s wives reaching out from her canopy to hold the rope of her camel during the caravan sequence. (As I recall It was noted in one of the excellent early 90s books on the film’s making that the hand, and thus Faisal’s wife, was played by a very male second assistant director.)