Ingmar Bergman was one of the pre-eminent intellectuals of international art cinema, and his brand—seen as probing, introspective dramas that sought to explore human nature at its barest, even despite the fact that Bergman’s output was quite varied and often times funny—remains singular today despite a fair share of introspective humanist peers and successors. The crises of Eric Rohmer’s characters are less existential; Kieslowski’s less political and more humanistic works are lyrical and abstract; the Dardennes’ are observational and understated. Bergman’s closest successor may be Turkey’s Nuri Bilge Ceylan, who has attracted similar comparisons to many of the same dramatists—Dostoevsky and Camus chief among them—for what is seen as a pursuit of existential themes, but Ceylan’s work is more political and is closer to Chekhov than Dostoesvky.

Perhaps because of this relative singularity, even as everyone from Woody Allen to Richard Linklater to Noah Baumbach sings his praises, Bergman is no longer entirely in vogue. His films are sometimes dismissed as old-fashioned in their self-seriousness, “too self-absorbed to say much about the larger world,” as the great critic Jonathan Rosenbaum put it, or perhaps even naïve in the belief that a film or work of art can answer big questions about life, God, and relationships. His equal and coexisting love for theater opens his films up to criticisms of theatricality, and in retrospect, it probably did not help him to be a contemporary of the French New Wave, a movement that won out as an influence in future filmmaking.

Persona, in spite of what first impressions it may give, is acutely aware of those criticisms, and it even tends to side with them. In the film, Alma (Bibi Andersson) is a nurse assigned to care for Elisabet Vogler (Liv Ullman), an actress who has recently willed herself to stop speaking. The two head to a seaside cottage, where Alma breaks the silence and recounts her views of herself, her fears, and her experiences to Elisabet. It is crucial that Alma is confused and uncertain, asking questions rather than making proclamations and trying more actively to “cure” Elisabet.” The questions that haunt her are typical of those that haunt the protagonists of Bergman’s best known films, albeit without the explicit mention of faith.

On one hand, this creates basic identification with Alma; on the other, our position is most similar to Elisabet, as we both learn all about Alma without having to speak a word. If Elisabet is analogous to us, Alma is analogous to a film, specifically a Bergman film because of her uncertain, questioning nature. Indeed, in one of the film’s most famous sequences, the camera is placed behind a transparent curtain, and we watch Alma walk toward the curtain and peak behind it. One does not need to look for long to find theory comparing a viewing experience to a translucent screen or a window, and an example can be found in the most famous scene of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. Persona, of course, is full of instances of foregrounding the viewer experience, namely the prologue, which shows celluloid running through a projector and a boy reaching out to touch what he sees on screen, as well as the end of the film, in which we see the crew itself as they film Alma. This curtain, and the placement of the camera behind it as we watch Alma through it is yet another instance of this, with Alma becoming the subject of the viewing experience—the film.

After she peaks behind the curtain there is an eye-line match to Elisabet looking at Alma, followed by a reverse shot back to Alma, at which point the film itself appears to burn up. This sequence not only aligns our point of view with Elisabet’s, both she and audiences studying something of interest (in Elisabet’s case Alma herself, as has been previously evidenced by a letter she wrote and Alma read, in our case the film), but it also rejects the idea of interaction between viewer and film. The screen becomes an interposing device that prevents the two from connecting, burning up when the two worlds start to converge. In another scene Alma urges Elisabet to talk, and the camera places itself between the two so Alma appears to be looking directly at the viewers, urging us to speak. We refuse, of course—we’re just watching a film—but she condescends to us anyway. Once again, we are aligned with Elisabet, refusing to speak to her.

It is crucial, then, that Alma only asks questions rather than offering answers. Our silence and the silence of Elisabet suggest that a film, especially a Bergman film, offers only questions, that it cannot claim any knowledge about topics as heady as faith and existence. In its deadly seriousness, Persona actually suggests that art is usually futile in its grasps for answers, exhibiting in autocritique what many of his detractors lambast him for.

But Alma’s incessant questioning also works as a radical (and it must be said, rarely imitated) technique in which the film is treating the viewer the way viewers so often treat films, as a vessel with secrets to uncover and answers to offer. Given this reworking of traditional viewer/film relations, it goes without saying that Persona does not offer any grand statements about…well, anything, but it make spectator/spectacle relations the subject of the film. Persona seems to toggle between the idea of film as a window or screen—something to look through, to watch something unfold and take hopefully learn from—and the idea of film as a mirror—something to look at, which reflects our own state back at us. Alma looking behind the curtain is an example of the former, but watching that scene disintegrate without consequence is a valiant rejection of such an idea.

Instead, the two approaches are best illustrated in the confrontation that culminates with the faces of the two actresses merging into one. In it, Alma and Elisabet sit down at opposite ends of the table with a picture of Elisabet’s child (the child in the film’s prologue) as Alma recounts Elisabet’s feelings about him. This scene plays twice, first from Alma’s point of view, beginning with an over-the-shoulder shot and gradually cutting increasingly close to Elisabet’s face, which begins to stare directly at the camera. Upon conclusion, it immediately repeats, following the same pattern from Elisabet’s point of view. The first time illustrates the “mirror” theory: The monologue is nearly undermined by the fearful and panicked expression on Elisabet’s face.

Thanks to Sven Nykvist’s brilliant cinematography, which takes extreme care with lighting, which even allows us to see the reflections in the actress’s eyes, every minor gesture or tic becomes hyper-semiotic, filled with emotion, feeling and meaning. At the same time, the close-up works as close-ups classically do, to create identification between the viewer and the character and generate empathy. The second time, by contrast, is forceful, harsh, and confrontational. Andersson looks directly at the camera as she delivers the line “you wanted a dead baby.” This is not the “window” theory per se, but rather an inversion of it that fits the film’s inversion of viewer-subject relations. Alma is looking right at us, assaulting us with her judgment and utter lack of sympathy. She judges us as we might judge a film, and we are frozen in place, as incapable of leaving as a film is willing itself to stop. We have no response, perhaps as so many of Bergman’s previous, nihilistic films have no response, no answer, no solution, just unanswerable questions blown up into defining questions. When Elisabet sucks the blood of Alma, as if trying to gain life from her—and by extension, the cinema—she is met with a slap. If Bergman’s earlier, equally known films are problematic for their seriousness, then Persona, according to this sequence, is a whole-hearted agreement, a reckoning on what Bergman must have seen as his own shortcomings and naivety.

In the end, Persona does provide, or at least suggest, an irrevocable faith in humanity. The film is full of close-ups of faces and displays of hands. The prologue depicts a nail being driven into a hand silently, but when the film burns up after Alma peaks behind the curtain, the same shot replays with a disembodied scream, turning a vaguely religious image into an emotional assault on something defining to us as human. It is Bergman’s best film, not least of all for the optimism that runs underneath its icy, horrific core or even for its shunning of theatricality that can be seen in so many of his other best films, but for its rethinking of both his own cinema and the medium as a whole, and for opening up his subsequent masterpieces, films like Shame and Hour of the Wolf and Fanny and Alexander, to shine without that hint of self-absorption and to speak more universally about the world at large.

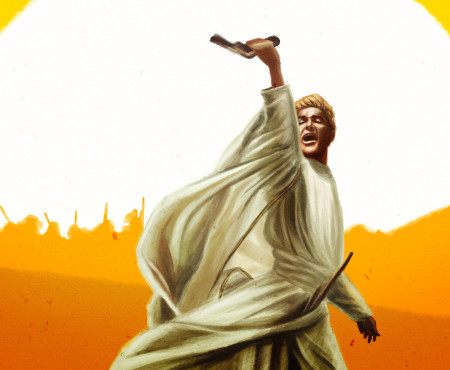

Note: If you dig the original illustration above, check out Alexandra Kittle on her Etsy page and follow her on Twitter here.