It may be only mild hyperbole to state that 2001: A Space Odyssey is, like The Jazz Singer and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Citizen Kane, one of the true monoliths of all cinema, a guiding and transformative force for the future. Divisive as it’s been since its release in 1968, 2001 long ago entered the realm of untouchable iconography. The soundtrack of mostly eerie and unnerving pieces of classical music; the opening, dialogue-free section depicting the slow but steady evolution of mankind in its earliest form; the jump-cut from said Dawn of Man to our conquest of space flight; HAL 9000’s plaintive and fruitless pleas for clemency aboard the spacecraft Discovery; and, finally, Dave Bowman’s journey “beyond the infinite” through a mind-altering Star Gate.

You know these moments and sequences even if you haven’t seen 2001 in years or ever. They are hard-wired into the fabric of cinema itself, referenced and ripped off and refracted in so many ways over the past 45 years. Stanley Kubrick’s filmography is overstuffed with classics; some may debate over whether this is even his best film of the 1960s. But 2001: A Space Odyssey is that rare beast: the influential piece of culture that hasn’t lost its potency.

2001, unlike so many films that have followed, is the purest embodiment of the awe-inspiring, thrilling event film. For all the common presumptions that Kubrick was a highly calculating, cold, distant, and often cynical filmmaker, there’s an undercurrent of hope in this film that’s impossible to ignore. Dave Bowman, as mundane as his life is (or as mundane as he treats his life as an astronaut aboard a spaceship whose true mission initially eludes him), is an avatar for the future, an example of where evolution could take us if we reclaim and reaffirm our inherently curious nature as a species.

No doubt, the irony that HAL 9000 is the most complex and layered character in 2001 in spite of being a computer, is heightened for maximum effect. (The mix of bitterness, misplaced pride, and confusion in the way he responds to the simplest of questions when challenged is incredible; Douglas Rain’s performance is a landmark in voice work.) But HAL represents the darker side of humanity, all paranoia and desperation and neurotic imperfections bottled up in one glowing red circle. The never-glimpsed alien power that lures Dave into the Star Gate sees something in his being, something that allows him to be chosen to reach a higher plane of consciousness. The very fact that it’s Dave who moves onward, into this new state of being, is proof enough of what Kubrick sees as the possible triumph of mankind.

“Possible,” of course, because 2001: A Space Odyssey has every intention of leading its audience only so far; even the visual details tell us a mere portion of the story. The dialogue is so purposefully sparse—one of the film’s many charms—, so there’s only a modicum of information dispersed throughout. The film’s episodic structure—meaning that we don’t meet HAL or Dave or Frank Poole until the end of the first hour—invites immersion as much as it throws some audiences off. Though it’s still one of the most technologically groundbreaking films ever made, 2001’s influence on the future of the science-fiction genre, by and large, ends there. What expensive, epic-length studio film nowadays is as patient as this one? How many of them luxuriate in the long take?

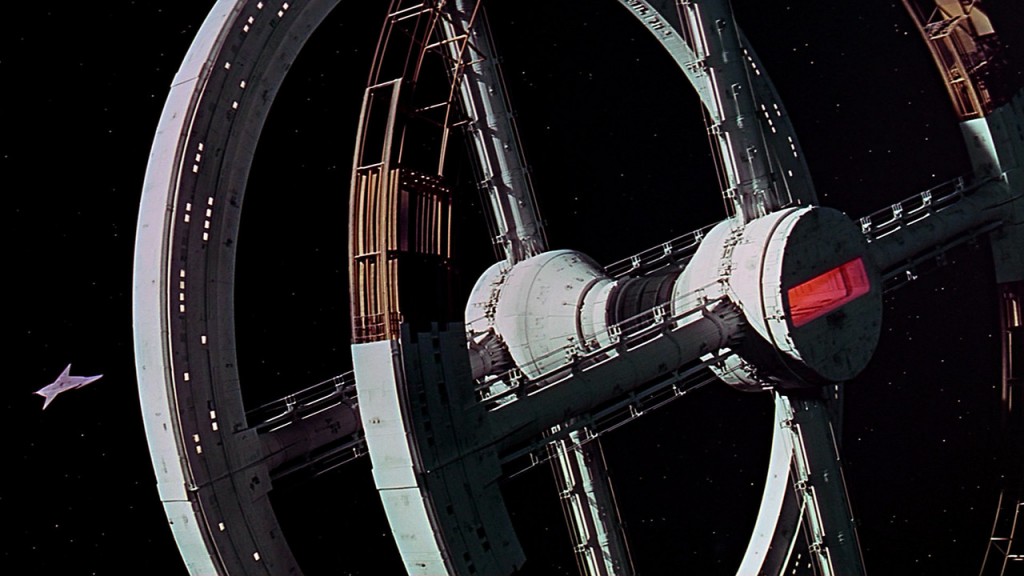

Marvel all you wish at the effects, which are still legitimately amazing to behold (even on Blu-ray) in 2014, but what’s truly jaw-dropping is how much Kubrick lets us drink in the visuals. The cuts from shot to shot, scene to scene, are so precise and never rushed. Some may see this as overindulgence, but the deliberate choices throughout, visually and aurally, combine to create one of the most exciting and challenging pictures of the decade. We are often meant to be dazzled these days, on a weekly basis, by what special-effects houses can create, but what differentiates 2001 from the rest of the genre, and from the rest of modern cinema, is its desire to inspire thought in the middle of an epic-sized package.

Thanks to the short-attention-span-driven Internet, previously infrequently used words have now been repeated so often that they have no meaning. Perhaps the best (and worst) example is “epic,” which currently means whatever the hell anyone wants it to: something cool, something awesome, something funny, or something intellectually stimulating can be called “epic” now and few people bat an eye. In particular, “epic” is a word that’s been throttled to death in the world of cinematic discourse, to the point where any new CGI-driven action movie can be called “epic,” just because. There was a time when “epic” was reserved for specific films or filmmakers. To call something “epic” didn’t simply mean you were praising a film for being witty or smart or cool; it was the definition of an event, a momentous occasion unlike any ever seen before.

2001: A Space Odyssey is the apotheosis of the old-school event film, a relic of the period of cinema when multiplexes weren’t as easy to find as the gas station in your hometown. For a film that’s so visually forward-thinking, so innovative in its storytelling and visual production, 2001 isn’t unwilling to indulge in some old-fashioned presentational techniques. The picture opens with an overture, although the spooky tones of Ligeti’s “Atmospheres” are designed to place unease in the audience instead of invite them into a big, splashy story; the end-title music is more exultant, as Strauss’ “The Blue Danube” soars on the soundtrack. And then there’s the cut from HAL 9000 watching his human charges talk about unplugging him to the “Intermission” title card, one of the most suspenseful and gasp-inducing edits in the film. Even within the structure of the more traditional three-hour roadshow picture of the mid-1960s, Kubrick’s able to be trickier and more defiant between and within these bridging moments.

Indeed, some aspects of 2001, specifically the design of the future-set sequences, are decidedly of their time. It’s easy, and facile, to snicker at the production design of “the future,” with its now-outmoded product placement (remember Howard Johnson’s?), and the sterile color scheme coupled with 60s-era computer monitors may seem a bit dated; however, the unusual and often off-putting production quality remains futuristic, as much as the notion of traveling to Jupiter would be now. Even more so, the fact that the humans in this film, in the early 2000s, treat a trip from Earth through the dark, forbidding beauty of space as if it’s a long train ride during which they can take a quick siesta. Dr. Heywood Floyd may be such a sleeper, nodding off on his trip from Earth to a space station on his way to the Clavius base on the Moon; although his humans seem nonplussed by their journeys, Kubrick is more engaged with the wonder and awe associated with space travel, back in the days when such a notion seemed less like folly and more like a foregone conclusion. Floyd is but a prop in that first sequence scored to the “Blue Danube,” as Kubrick nearly fetishizes a space shuttle slowly docking with a larger, spinning, spherical station.

Stanley Kubrick was not just one of the great filmmakers, he may well have been the filmmaker of the 20th century. Kubrick’s auteurish tendencies were not defined by a specific genre; he made war movies, noir, horror, satire, and even swords-and-sandals epics. In some respects, though, there’s a demarcation in his filmography, between the features he made up to and including Dr. Strangelove and those afterwards. Though Spartacus was intended to be an event picture like Ben-Hur and other similarly sprawling historical tales, 2001: A Space Odyssey is the touchstone of Kubrick’s career, the moment when he stopped approaching mythic status and became a legend of the medium. With 2001, he began to wear his auteurism comfortably, his brilliance now wholly, undeniably formed. In creating this monolith, he’d evolved to a higher cinematic form.

3 thoughts on “History of Film: “2001: A Space Odyssey””

Epic essay! (sorry). I really like your point about how Kubrick lingers on the special effects. That’s what struck me the most on my most recent rewatch. The long takes really let you soak in all of the grandeur and detail in the effects.

Pingback: 2001: A Space Odyssey Review and Blu-ray Features | HitMoviesComics

I saw 2001 in a theater during its original release, and as an 11-or-12 year old, seeing this movie in one of southern California’s gigantic wide-screen theaters utterly crushed me. I was overwhelmed by the sheer power of the visuals and sound and I was in a daze for a couple of days. In a way, the movie changed my life. 2001 showed me how powerfully and profoundly you can tell a story almost exclusively with visuals..

A few points — at the time, actual trademarks were almost never shown in movies. The use of real corporate names and logos (Pan American Airlines, Hilton Hotels, Howard Johnson’s) was unusual, and seeing these names on a space-shuttle type vehicle and on signage in a space station helped create the feeling of an ordinary and believable future where you’d snooze during space travel, although just like the Atari logo you see in Bladerunner, they are, unfortunately, dated. There were some oddly accurate predictions, such as flat-screen TVs in the backs of airline seats, iPads to view news on, and ‘glass cockpits’ (multi-function video displays on instrument panels instead of dials and gauges) in the various spacecraft. As a kid, the astronauts’ news pads were one of the few things I had trouble suspending belief about, since the only video displays I had ever seen were CRTs. Millions-of-years-old alient artifacts, wormholes and sentient computers, not so much.

When I saw this in the theater in 1968, after Heywood Floyd made the video phone call from the space station, the price shown on the screen ($1.70) got a big laugh from the audience because it seemed so absurdly expensive.

Originally, 2001 had a subplot about Cold-War tensions and nuclear weapons in space, but only one small hint of this is left. At the end of the ‘dawn of man’ sequence, Moonwatcher throws his bone into the air and we cut to an an unidentified piece of space hardware. This is an orbiting nuclear missile launcher from the deleted subplot. We swap the bone for nukes — we’re the same apes, with more powerful weapons. The bone-to-space cut is still a clever way to move us forward a few million years, but it originally had additional context and meaning.

I still have the original 2001 program book. I didn’t understand some things in the film until years later, but the program only served to further confuse my young self. The text starts out with the statement ‘behind each of us stands thirty ghosts,’ and goes on to state that the number of stars in our galaxy is approximately the same as the total number of all human beings who have ever lived — so we can each have our own star as a personal heaven or hell. To this day, I wonder who wrote this text, who approved it and why anybody felt it was appropriate.