Editor’s note: Days of Heaven is one of the 10 best films of the 1970s voted on by staff, friends, and readers of Movie Mezzanine. For the sake of surprise, we’ll wait to reveal where this and every other film ranks on the list until the very end. We hope you enjoy.

…

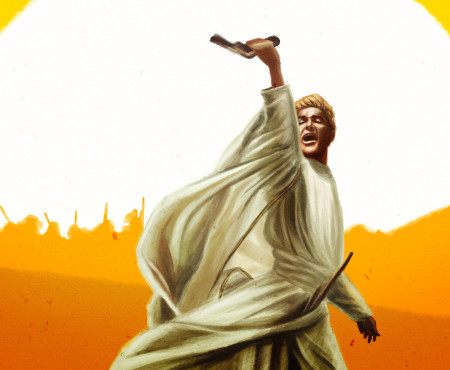

Terrence Malick’s 1978 film Days of Heaven is a tale of two lovers on the run from the law who hide away on a farm during harvest. It’s a meditative, visually stunning drama set in the harsh days before the U.S. entered World War I. Few people would idealize this time as much as Malick, but there’s still a current of melancholy running beneath the gorgeous photography that acts as a reaction to the romantic worldview of the studio era. Malick may believe love is worth fighting for, but he also believes that it’s very, very hard.

Badlands, his debut feature, is more structured around narrative than a lot of his work. The Tree of Life, The Thin Red Line and The New World, meanwhile, blend visual sumptuousness while emphasizing ideas and tone. Days of Heaven is the connective tissue—in it, we see Malick evolving both as a visual artist and a storyteller. It’s a work that asks its audience to reconsider how they view and interpret films. More than an experimental film from Europe or a stripped-down piece of New Wave cinema, it requests that the viewer be willing to forget narrative and simply be lost in visual emotion.

We begin in a Chicago steel mill in 1916, unable to hear anything but the loud roars of fire and machinery. Our protagonist, Bill (Richard Gere), accidentally kills the foreman during an argument, so he flees to the Texas Panhandle with his sister Linda (Linda Manz) and his lover Abby (Brooke Adams), the latter of whom pretends to be another sibling. They’re soon hired by a wheat farmer (Sam Shephard) to help with the harvest, but things start to get messy when he starts to fall in love with Abby (he thinks Bill is her brother). The farmer has an unspecified disease and might not live long, so Bill tells Abby to marry him, hoping that he’ll die and leave her enough money to take care of them. However, as time goes by, the farmer doesn’t seem to be very ill, and Bill grows increasingly aggravated as he watches Abby gradually fall for another man.

It sounds like a silly classic Hollywood melodrama, but the plot is secondary to what makes Days of Heaven such an especially astounding film. The story is told through disjointed narration by Bill’s little sister, Linda, and it’s easy to dismiss her comments considering she seems to not yet have a complete grasp of the world. As her voice roams the wheat fields, it shifts in comprehension and lucidness; one moment, she’ll be discussing how she felt about moving in with Bill and Abby, and in the next she’ll hypothesize why Bill left with a flying circus. She defines the relationship dynamics of Bill and Abby in ways we barely understand, only to fall into a tangent: “I’ve been thinking what to do wit’ my future. I could be a mud doctor. Checking out the eart’.” This is the story according to a pre-teen, so its accuracy is always in question.

Where Days of Heaven thrives is Malick’s aesthetic vernacular. He doesn’t quite reach the heights he would achieve in 2005’s The New World, but the ever-evolving seeds of his visual language are on full display. We move from wheat fields where a minister prays for a good yield to the post-sunset glow of the harvest, the camera allowing us to take in the beauty of what is. Later, the same field is lit by a locus-consuming flame, a stark reminder of the beauty that was. There are constant visual repetitions that evoke a mood of loss, of cycles doomed to repeat or die. At the end of the film, our three main characters go on the run again, and this time their fate is far less hopeful.

Since the 1970s, filmmakers have been looking for more ways to redefine the romanticized worldview that cinema dreamed up during ‘30s and ‘40s. How can we capture an idealized love while still remaining true to human experience? In Days of Heaven, Malick walks the line between the romantic and the realistic, showing us that it’s possible to have the best of both worlds.

2 thoughts on “History of Film: ‘Days of Heaven’”

This is still my favorite Malick film. I was just ravaged by those images and how Malick was able to make a love triangle be so much more.

I still go for THE NEW WORLD and BADLANDS, if we’re talking favourite… but DAYS OF HEAVEN does a lot for him in my mind.