The Church of Scientology is famously thin-skinned as institutions go, but you can’t really fault them for wanting to take a collective hit out on Alex Gibney’s Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief. If the film isn’t quite the polemic its title suggests, in practice it might actually be more tactless, a greatest-hits compilation of Saló-esque misdeeds from rich people in nice suits, as recounted by some awfully brave talking heads who’ve managed to get themselves off the carousel at great personal and professional cost. Gibney is a prolific documentarian with a seemingly boundless appetite for juicy contemporary issues, and, true to its maker, Going Clear is itself a prolific sort of film, endlessly stockpiling ludicrous and probably true anecdotes from the now 60-year-old tradition that ushers its adherents through to enlightenment (or clarity) via tiered steps that can only be climbed through intensive auditing and intensive spending—an American original if there ever was one. Coupled with Gibney’s fleet pacing and smirking tone, those unseemly stories make Going Clear a pretty cracking affair, but they don’t do much in the way of advancing an earnest argument about either imprisonment or belief. Though it’s riding high after its HBO premiere now, it’s hard to shake the feeling that the film may be best remembered as a repository of strange alt-religious trivia to rival Scientology’s Wikipedia page.

The film adapts Lawrence Wright’s National Book Award finalist of the same name, an exposé that nicely lingers on some of the human voices muffled by an institution with a formidable history of litigation and nearly indefatigable resources. Though he’s more of a benevolent godfather figure to the project than its single guiding light, Wright is nevertheless on hand to supply some of the juicier nuggets, like a quizzical reading of the e-meter, Scientology’s spiritual equivalent to the tricorder, which scans a body in hopes of finding the spot where a person is most “aberrated” (let’s say besieged) by the presence of traumatized beings from a bygone era. The aim seems to be twofold: to introduce the Church’s foundation in creator and shepherd L. Ron Hubbard’s pure hucksterism—the good thing about religions, he seems to have figured out early on, is that they don’t have to pay taxes—and to provide a confessional platform to a handful of its recent high-profile excommunicates, from Paul Haggis to the Church’s former senior executive, Mike Rinder.

It’s in this second aim that the film offers something a bit more humane than just a comic grotesquerie about a religion that responds to its parishioners’ healthy bouts of skepticism by putting them through the ringer. One is perhaps most struck by the refugees’ quiet dignity as they recount a series of increasingly grim humiliations at the hands of the Church’s quicksilver leader, David Miscavige. They speak of past assaults and ornately designed (but unofficial) prison sentences in one of the Church’s many euphemistically named rehabilitation centers for off-brand members and their loved ones as if such things were simply their due—the natural consequences of a life given in service of something bigger than themselves.

What doesn’t quite come across, though—whether it’s because the subjects aren’t capable of answering or because Gibney can’t bring himself to ask—is what the filmmaker thinks about how the way such yearnings for spiritual fulfillment and community seem to result in the related desire to hand over the keys to one’s liberty. Gibney is so focused on cataloguing the Church’s irrational positions, shoddy doctrines, countless human-rights violations, and gauche aesthetics that he doesn’t seem to feel it important to ask what Scientology might actually offer vulnerable people like John Travolta, who we are told was troubled before his leap of faith, as if that should explain it all. Only Haggis—who, in his delicate bearing and lilting Southwestern Ontarian tones, seems quite different from the blowhard who attributed his Crash Oscar to Brecht not so long ago—makes a compelling case for why any of this individualist sci-fi hokum might have appealed to a struggling screenwriter with relationship problems.

The trouble might be that Gibney’s campaign to deliver a shocking scoop for Sunday-night television is at odds with the difficult lived experiences of his subjects. As a result, Going Clear is probably more entertaining—and self-enchanted by its own entertainment value—than an exposé about people who’ve had their lives stolen from them really ought to be. Between his Errol Morris-cribbed dramatic recreations, his cheeky conceptual tutorials about auditing modeled after 1950s educational videos, his wailing ondes Martenot score beamed in from Star Trek, and his cheerful infographics about Scientology’s top-secret higher levels of enlightenment—which sound a bit like different kinds of drivers’ licenses to the uninitiated—Gibney seems to be conducting a mini-tour of informational nonfiction aesthetics. Going Clear seems as preoccupied with demonstrating Gibney’s fluency with the genre—what we might call the “information dump doc”—than it is with delivering the actual information. Gibney’s aesthetic self-consciousness is not inherently a bad thing, but it strikes the wrong note here, giving an air of condescension to not only things people actually believe, but also, more troublingly, traumatizing experiences people actually survived.

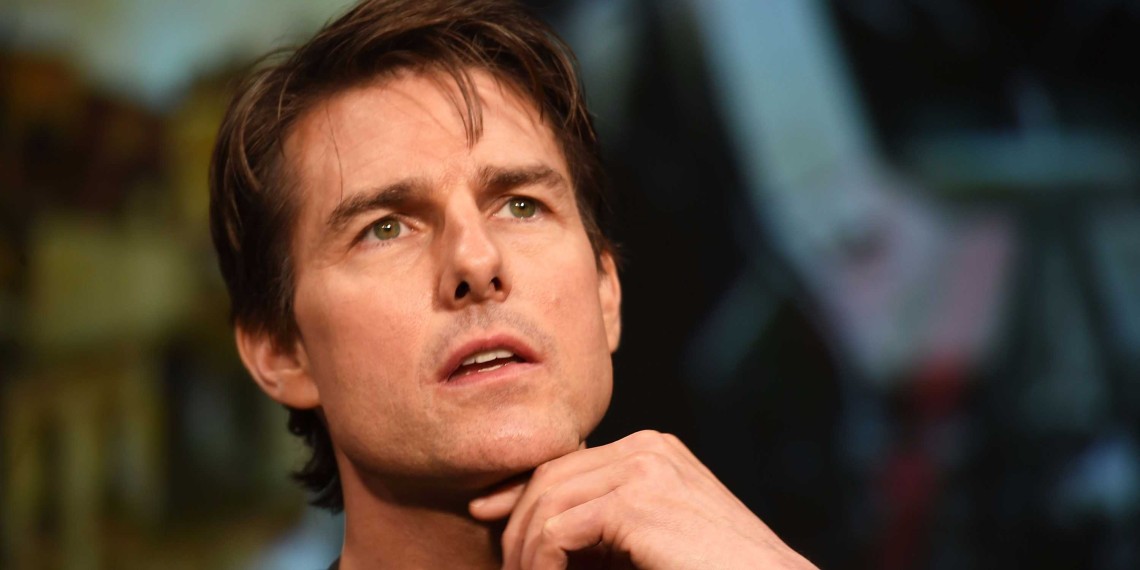

Indeed, for all the weird archival footage of Tom Cruise dissolving into a flurry of impenetrable buzzwords and punching gestures when presented with the Church’s top honor, Going Clear is a strange sit mostly because its darkly comic tone doesn’t quite support the painful stories its prized subjects are telling. This is not to say that Gibney is unaware of the seriousness of human trafficking and child abduction, just two of the heavy charges convincingly laid at upper ranking Church members here; his previous work is a sobering argument to the contrary. But there is an indelicacy to his touch here that neutralizes the film’s impact as anything but a glib, rollicking tour through strange lands.

5 thoughts on “Going Glib: On Alex Gibney’s Fleet, Tactless Scientology Exposé”

I don’t see how any viewers could watch any of GOING CLEAR’s footage and see smirk or condescension in Gibney’s work at all. Certainly not with the charges mentioned and the gravity of the make-shift prisons, stalking and mental abuse portrayed.

So Angelo, you were unmoved by the accounts of those who were finally able to break free, you know, literally escape?

Hipster review. Trying to prove he’s too cool for school. C-, must try harder.

Hi Mr. Muredda. If I understand correctly, Gibney felt that concentrating on the tax exempt and disconnection (shunning) issues, were the best place to start. He actually did not have enough time in this 2 hour documentary to touch on, with any sort of specificness, If he had been able to go any deeper, I’m afraid many people would have found it too incredulous to believe.

I think if Alex Gibney does the sequel he has inferred is a possibility, people will be ready for the deeper and darker horrors that are orchestrated in the senior management, of this vile crime ridden mafia like, sinister organization.

Trying too hard here Angelo. Get serious. Sorry he spent time much time on the near psychotic doctrines and human rights violations of the Church. Nothing glib about this at all, maybe you didn’t feel Scientology got a fair shake.Sigh