Republished and altered from our coverage of the 2013 LA Film Festival.

Reviewing a film like Fruitvale Station is challenging. Movies based on true stories are already hard enough to critique on a plot or character level, but when you’re dealing with such a harrowing, difficult story as the one about the final days of Oscar Grant, his wrongful murder at the hands of a racist policeman, and the aftermath following it, there are a lot of things that need to be acknowledged, regardless of your overall feelings for the film as a whole. As an account of that horrific incident, Fruitvale Station is a very powerful piece of cinema, with incredible performances and deeply human direction as it follows the moments leading to Oscar’s murder, both small and large. Yet it’s the kind of movie where that real-life incident ends up hanging over the entire film, almost holding it back from being able to be great on its own merits.

When the film is firing on all cylinders and showing us Oscar’s final moments in all its haunting eminence, it’s masterfully done. It perfectly captures what the panic and intensity of the now infamous incident must have been like, with a gritty, handheld style reminiscent of Paul Greengrass’s United 93, crescendoing into an absolutely heartbreaking final 5 minutes bound to linger with just about every viewer.

And yet, as near-perfect as the climax is, Fruitvale Station is considerably less successful in its depiction of Oscar’s everyday activities. Regardless of how “accurate” the events we’re witnessing are, it really should be noted how Coogler leans much too heavily on the story’s fatalism. The film begins with what appears to be real cell-phone footage from the incident at Fruitvale Station, and never throughout the rest of the film lets us forget how the story is going to end. A lot of the authenticity is removed from what we bear witness to on screen as a result, and we’re left unable to appreciate these small moments on their own.

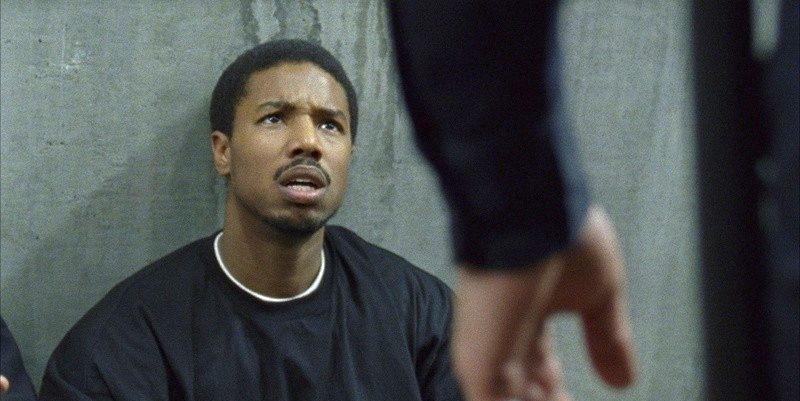

What brings it all around is a terrific cast and some extraordinarily restrained pacing. Michael B. Jordan manages to make Oscar Grant incredibly likable and human, never resorting to using the more martyrly icon that the public has created and focusing on the real person at the center of it all. Meanwhile, Octavia Spencer and Melonie Diaz are powerful as Oscar’s mother and wife, while child actress Ariana Neal is effective as Oscar’s young daughter.

Yet as wonderfully handled as the performances and the climax are, the script is very problematic. For as much as Michael B. Jordan works to make Oscar a fully-realized human character, Coogler’s script idealizes him too much, barely delving into some of Oscar’s deep-seated flaws ranging from relationship cheating to drug dealing to a short temper.

Most emblematic of this approach is the scene in which Oscar flashes back to a memory of his time in prison, and then chucks a bag of marijuana into the ocean, hoping to start a new beginning. It would’ve been much more interesting to see Oscar actually battle these demons from his past, but Coogler is so intent on lionizing every single aspect of Oscar’s life that the nuance becomes absent.

But the script’s biggest issue lies in a certain moment in the film’s otherwise incredibly well-executed climax. I won’t bother saying what it is specifically, but Coogler decided to tie some of the real-life events with entirely fabricated ones from Oscar’s “past” in a way that almost sucks out all of the immediacy and legitimacy from the moment in the titular BART train station. This scary, random act of violence is all of a sudden reduced to a moment dictated by destiny, thus distracting us from the real human beings at the center of it all and becoming a story about people literally becoming symbols.

Ultimately, Fruitvale Station does work, but it’s marred by such problematic writing and direction that one can’t help but wonder what a filmmaker who is more interested in the subtleties and real truths of this story would have brought to the table. It’s a movie that’s as emotionally powerful as it is wildly imperfect.