Best Scene: Moonlight

“Who is you?” A man in his twenties asks this of “Black,” or “Little,” or Chiron in the final third of the best film of 2016, Moonlight; it’s a fitting query that serves as the core of Barry Jenkins’ new film, a triptych/coming-of-age hybrid depicting the life of a young gay black man growing up in Miami and struggling with his identity. The major setpiece of the last portion of Moonlight largely takes place at a hole-in-the-wall diner where Chiron’s only true friend throughout his childhood, Kevin (Andre Holland, mesmerizing), now works after some time away in prison. Chiron, known as “Black” to his friends and cohorts, has had a weaving road of his own, with crime in his past (and present). Trevante Rhodes, as “Black”/Chiron, is exceptional at portraying the braggadocio that defines his current work as well as the wounded, innocent child who hides just behind that thin veneer of bluster; Jenkins’ script, as well as Holland’s performance, does a phenomenal job of puncturing that veneer throughout their reunion at the diner, which is at once suspenseful and romantic, cutting and heartbreaking. In a year of great films and scenes, this stands above the rest. — Josh Spiegel

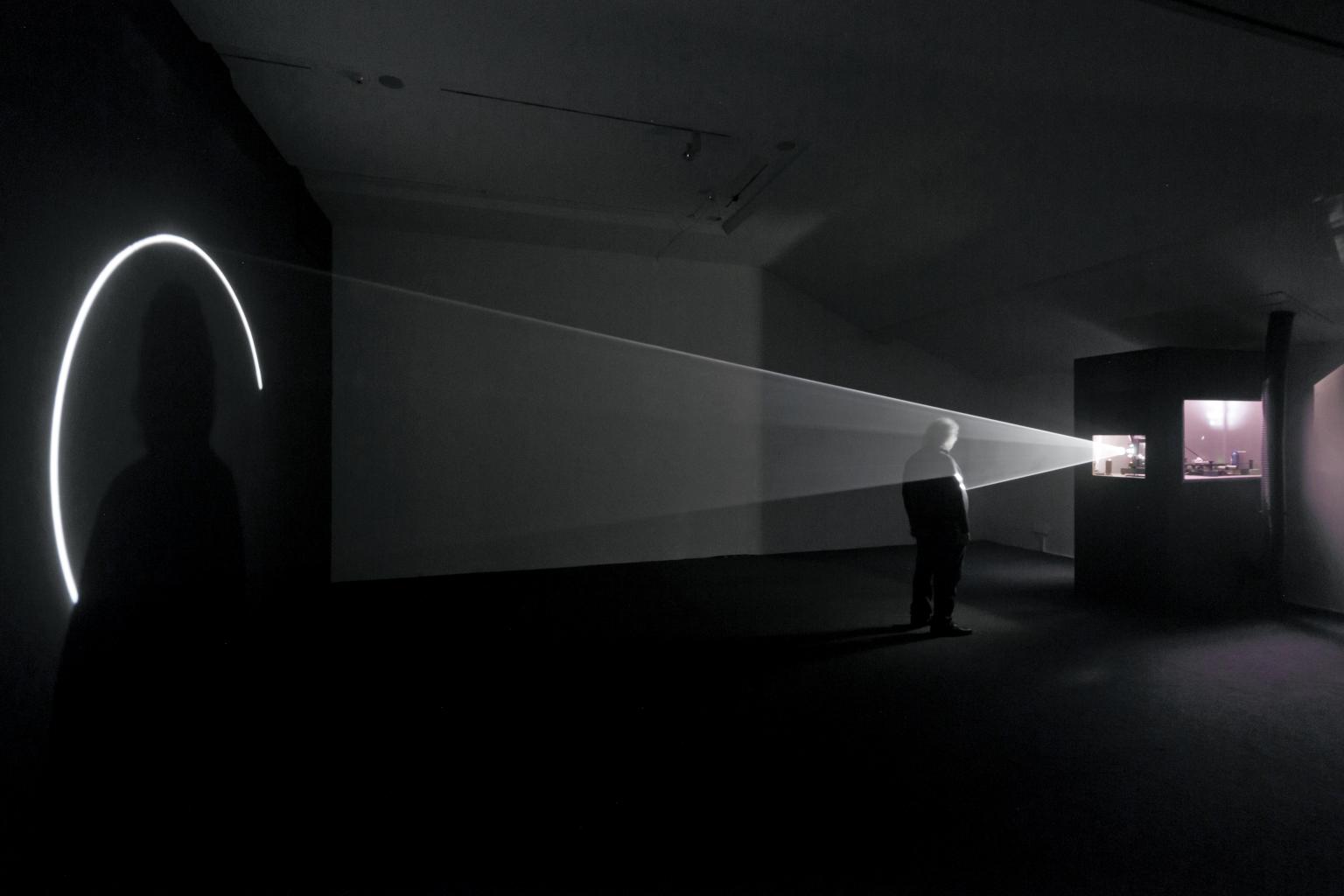

Best Discovery of 2016: Line Describing a Cone

The most eye-opening pre-2016 cinematic discovery I made this year didn’t have characters, a plot, themes, or even any music or cinematography to speak of. Instead, it was simply a full circle drawn slowly over the course of 30 minutes. But project this onto a wall in a dark room with a heavy amount of smoke in it, and you’ll be astonished to see the conical shape the light from the film projector begins to form. That’s the premise behind Line Describing a Cone, a structural film from 1973 by Anthony McCall that I had the pleasure to witness firsthand in a basement in Brooklyn. Pleasure? Make that “open-mouthed astonishment,” because I genuinely had never seen anything like it. This was the kind of wholly unexpected discovery that not only gratified the kind of risk-taking that goes with venturing into the repertory-cinema circuit, but also refreshed my sense of wonder at the vast possibilities of this wide-ranging medium we celebrate here at Movie Mezzanine, reminding me that there’s still a lot that can be done in cinema. The fact that this was conceived more than 40 years ago makes it all the more sobering. — Kenji Fujishima

Best Actor Wasted in a Tiny Role: Michael Stuhlbarg, Doctor Strange/Arrival

We’re all familiar with the sensation. That click of recognition that occurs even when you’re deeply engrossed in the latest must-see flick at the multiplex. A new character enters the scene, and a lightbulb suddenly goes off. “Oh!” you think, “it’s that guy/girl!” Surely, this character played by such a known actor is significant! And then as soon as they appear, they’re gone. Top-level talent relegated to a bit part.

2016 has no shortage of name actors cast in improbably tiny roles, but only one stands out as especially egregious. But first, a few honorable mentions. Nocturnal Animals sees Laura Linney appear for a single scene, as Amy Adams’ helmet-haired Southern mother. Michael Shannon’s short but endearing turn in Loving as the Life magazine photographer tasked with capturing the Lovings at home takes up no more than 10 minutes of screen time. And Julia Stiles returns to the Bourne franchise in Jason Bourne only to be unceremoniously dispatched before the first act is up.

But the actor who tops this category had the dubious distinction of being wasted in not just one, but two films in 2016. Michael Stuhlbarg (A Serious Man, Boardwalk Empire, Steve Jobs) briefly appeared as a tut-tutting second banana in both Doctor Strange (as Strange’s surgical rival Dr. Nicodemus West) and Arrival (as a CIA agent skeptical of Amy Adams’ method of communicating with aliens). Neither role is dramatically hefty, nor are they particularly memorable, save, perhaps, for the twin experiences of making one stop and think “say, isn’t that the Santana Abraxas guy?” Hopefully, with roles in upcoming films by Guillermo del Toro and Luca Guadagnino, 2017 will serve him better. — Mallory Andrews

Best Set Design: The Witch

Former stage designer Robert Eggers made his directorial debut with this Puritan-era slow-burn horror film, which takes place at the edge of an isolated New England wood in what seems to be a perpetual dusk. Eggers has a clear eye for the tonal power of mise-en-scene, and every prop–from a fresh apple to an unblinking wild hare to an ever-growing pile of firewood–is revealed, sometimes lurking at the frame’s edge, with a nearly unbearable sense of foreboding. When a banished family’s newborn child goes missing, accusations of witchcraft abound, and the family’s dreary farm (one of many set pieces that was painstakingly and authentically created by Eggers’ team) takes on a strange juxtaposition with the nearby dark forest. It quickly becomes apparent that danger lurks both within and without the woods, and as each character is gripped by isolating superstition, movements within the farm begin to feel heavier, weighted down by the lonely fear built into its very foundation by the family’s overzealous patriarch (Ralph Ineson). By the time eldest daughter Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy) sheds her bloodstained dress and calls to the voice in the darkness, the woods feel less like a death sentence and more like a promise of freedom beyond the walls her father built. — Valerie Ettenhofer

Best Discovery of 2016: Mahjong (among others)

Most of my favorite 2016 discoveries were project-related. For various podcasts, I watched Jacques Rivette’s Duelle and Noroît, Jacques Tourneur’s Canyon Passage, Terence Davies Distant Voices, Still Lives and The Long Day Closes, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure and Tokyo Sonata, Jean Renoir’s La bête humaine and Swamp Water, Takeshi Kitano’s Sonatine and Violent Cop, Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Phantoms of Nabua, Peter Greenaway’s Prospero’s Books, Spencer Williams’s Dirty Gertie from Harlem USA, and Kinji Fukasaku’s five-film series The Yakuza Papers. For various writing projects, I saw Sion Sono’s Love Exposure and Suicide Club, Derek Yee and Law Chi-leung’s Viva Erotica, DW Griffith’s Isn’t Life Wonderful and The Unchanging Sea, Ringo Lam’s School on Fire and Burning Paradise in Hell, Matías Piñeiro’s Viola, Roger Michell’s Persuasion, Stephen Chow’s God of Cookery, Barry Jenkins’ Medicine for Melancholy, Patrick Leung’s Beyond Hypothermia, and Anna Biller’s Viva. If I had to pick one favorite, it’d be Edward Yang’s Mahjong, arguably the great director’s best film, a distillation of the disaffected youth of A Brighter Summer Day, the punishing romanticism of Taipei Story and The Terrorizers, and the panoptic warmth of Yi Yi. The final moments are the most romantic images ever to come out of the New Taiwanese Cinema. — Sean Gilman

Other Best Discoveries of 2016

- Mallory Andrews: Design for Living

- Jake Cole: Noroit

- Alex Engquist: Up, Down, Fragile

- Vikram Murthi (in alphabetical order)

- A Brighter Summer Day (Edward Yang, 1991)

- A Nos Amours (Maurice Pialat, 1983)

- Army of Shadows (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1969)

- Band of Outsiders (Jean-Luc Godard, 1964)

- César and Rosalie (Claude Sautet, 1972)

- Forbidden Games (René Clément, 1952)

- Gate of Flesh (Seijun Suzuki, 1964)

- My Sex Life…(Or How I Got Into An Argument) (Arnaud Desplechin, 1996)

- State and Main (David Mamet, 2000)

- The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (Joseph Sargent, 1974)

- Emma Stefansky: Vertigo

Tomorrow: Our contributors’ choices for the best debut of 2016, best Chinese-language film, best sex scene, and more.

4 thoughts on “The Year in Film, Superlatives (Part 1)”

Pingback: The Year in Film, Superlatives (Part 2) | Movie Mezzanine

Pingback: Movie Mezzanine’s Year In Film, Superlatives | A Constant Visual Feast

Pingback: The 25 Best Films of 2016, Part 1 | Movie Mezzanine

Pingback: The 25 Best Films of 2016, Part 2 | Movie Mezzanine