2016 was a landmark year for cinema, because it was truly the worst year ever. That’s what a lot of people on the Internet said: it was the year movies stopped mattering, it was the worst year for summer movies, and it was the worst year—period–for movies. (That last link is particularly bold, its claim being made in February of 2016.) Of course, now that the year is finally, mercifully wrapping up and 2017 is shortly upon us, it’s just as easy to argue that 2016 was one of the best years for movies since the medium began over 100 years ago. Yes, this was the year of Suicide Squad, Trolls, and Independence Day: Resurgence, but it was also the year of Moonlight, Kubo and the Two Strings, Fences, and more. All week long at Movie Mezzanine, our writers and editors will be bidding a fond farewell of the year of film that was 2016. Today and yesterday, we’ve got superlative categories aplenty in which to award various films, filmmakers, and more, as well as our writers’ picks for the best discoveries of older films that they made in 2016. No more preamble–let’s get to it.

Most Surprising Film: The Shallows

Sharks terrify us because of how alien they are. They have no feelings, no friends, no jobs, and they seem to spend their days only looking for the next thing to hunt, mindless, casting around for the smell of blood in the water. When you look into a shark’s eye, nothing looks back but your own reflection. Given their creepy nature and the narrative of horror that’s been irresponsibly built around them thanks to fallout from Jaws and Discovery’s Shark Week, I expected to dislike The Shallows. As it turns out, I was shocked by how much I enjoyed it.

It begins with a montage that’s essentially a love note to the crystalline beauty of the ocean. Blake Lively’s Nancy is practically a sea creature herself, zipping through the waves with a confidence and familiarity of someone who knows the ocean. And when the ocean finally turns against her, as the ocean does, she’s prepared.

Director Jaume Collet-Serra seems to know that the ocean can change from paradise to hell in mere minutes, because that’s just the way the natural world works. The Shallows is shark horror (if it’s not a genre, it should be) that doesn’t treat the shark like a machine, or nature as something to be defeated. For Nancy, the shark is something to figure out, an animal with thoughts and needs. The Shallows is not a tale of man defeating nature, it’s a survival story: Nancy gets back on land because she’s smart, she’s quick-thinking, and — most of all — she’s lucky. If nature were something to be competed against and overcome, she’d never get back in the water. What would be the point? As it is, we see her again at the end, surfboard at the ready and teaching her sister how to ride the waves. And smiling. — Emma Stefansky

Best Discovery of 2016: The Umbrellas of Cherbourg

Whatever else can be said of 2016, this much (for me) is true: this year has felt exceptionally lengthy, well past the traditional sense of a 365-day period. I say this because, in scouring my Letterboxd account to figure out which old film would be my pick for best discovery of the year, I realized that Jacques Demy’s vibrant, lush, bittersweet romance The Umbrellas of Cherbourg is one I’d seen within the first weeks of 2016. Though I did see many other fine older films that were new to me this year, there really can’t be any other choice than this excellent blend of Arthur Freed-era musicals, in Demy’s use of color and depiction of a young, blossoming love story between Guy (Nino Castelnuovo) and Genevieve (Catherine Deneuve); and of French New Wave storytelling, specifically in the core theme of young love left by the wayside. It’s, of course, mere coincidence that one of the standout films of 2016, La La Land, owes such a heavy debt to Demy’s 1964 classic; The Umbrellas of Cherbourg may be getting name-checked a lot in the next few weeks and months, which will hopefully lead many others to do what I did this past January: discover a true cinematic gem. — Josh Spiegel

Best Debut: The Edge of Seventeen

In the opening scene of Kelly Fremon Craig’s debut feature The Edge of Seventeen, there’s a shot that shows Nadine Franklin (Hailee Steinfeld) walking urgently through the halls of her high school to interrupt her favorite teacher’s lunch to tell him she intends to commit suicide. The camera follows her and tracks up her body until her entire outfit can be seen. She’s wearing sneakers over tights, leading up to a skirt, and finally a men’s bomber jacket. Her outfit is an extension of her character and Fremon Craig frames Nadine in a way that emphasizes her look and personality through fashion. It’s a simple sequence, but speaks volumes to the level of detail given to Nadine that makes her feel immediately iconic and cinematic in a way that very few American movies about teenagers have been in the last few years. Nadine is like many teenagers in the sense that she can’t see her everyday problems as anything less than the end of the world; the greatest strength in Seventeen is that the film treats those problems exactly as Nadine does. It’s a total point-of-view recognition and key to making this movie have impact, depth, and understanding in its characters. Nadine is not here to be taught a lesson or become a cautionary tale, as many films about teenagers tend to do; instead, she exists fully as her own person moving through her problems from moment to moment however she sees best. It’s truly a breath of fresh air for a film of this caliber to exist and treat a teenage girl’s struggles, complexities, and deficiencies in an empathetic and profoundly loving way. — Willow Maclay

Biggest Disappointment: American Honey

Seven years on from release, Andrea Arnold’s Fish Tank still stands out as one of the most thoughtful portrayals of sexual awakening put to screen. The strong sense of social realism in that film is all the more realistic for the casual, unforced way it finds a place within the story. Arnold’s latest film, American Honey, coming five years after her last, the pretty baffling Wuthering Heights, is as self-conscious and misguided as Fish Tank is assured and accurate.

Featuring an American setting transformed beyond recognition and a restless camera, intrusive to the point of self-absorption, the film fails to be anything more than a stylistic exercise, an astonishing fantasy of working-class American youth transformed into something akin to a particularly racy American Apparel ad. Just as artificial is the blossoming of the wooden young lead into a mature person, with a series of useless repetitions, hilariously on-the-nose musical cues, and poor dialogue that unfortunately never creates the intended sense of poetry, instead contributing to some of the most insultingly obvious signposting in recent memory. — Elena Lazic

Best Discovery of 2016: Five Films Directed by Women

In 2016 I participated in the 52 Films by Women challenge, pledging to watch at least one film directed by a woman per week for a year. I’m happy to say I got up to 100, and it was incredibly rewarding – I watched a lot of things I might never have bothered with, and ended up loving them, I found some new favorite directors and many new favorite movies, and overall it was an extremely positive and fulfilling experience. I’ve picked five of my favorites, and they turned out to be five stories about women. As much as I love female takes on masculinity in film, I drew a lot of strength from these stories and their characters. — Sydney Wegner

The Slumber Party Massacre (Amy Holden Jones, 1982)

The Slumber Party Massacre takes a predictable slasher framework – teenage girls trapped in a house, serial killer on the loose – and brings it to life with a creepy and silly synth score, rich colors, and natural, lovable performances. There are as many jokes and funny jump scares as there are thrills and horrors, but besides being entertaining as hell, it’s thematically fascinating. It can be analyzed about 10 different ways – are the lingering shots of the girls’ naked bodies exploitative, a comment on the male gaze, tongue-in-cheek satire, pandering to the audience, or all of the above? As interesting as it is, it’s also just delightful to watch, a perfect streamlined slasher with an unforgettably weird killer (actor Michael Villella has said in interviews that he based his movements on those of a peacock). In my mind, it isn’t feminist solely for its wry commentary on the genre, but because it gives these characters room to be real people. Even though they’re shown getting murdered and getting undressed like characters in any other slasher movie, they are never reduced to interchangeable screaming objects. They are people you can imagine having a conversation with, and everyone knows a movie is scarier when death comes for characters who feel real.

Dogfight (Nancy Savoca, 1991)

Dogfight is deceptively simple. The night before leaving for Vietnam in 1963, a group of teenage soldiers hold a “dog fight” contest, in which each boy has to bring the homeliest date out to a dance, with the winner receiving a pile of money. Eddie (River Phoenix) picks up Rose (Lily Taylor) at a coffee shop where she works, but after talking with her, he begins to feel guilty about his cruel ulterior motives. The two end up spending an emotional night together, and the way their relationship grows and changes over the course of the film is remarkable. Dogfight has two of the best performances I’ve ever seen, soaked in awkward glances and gesture; their characters seem so real that by the end, I was literally on the edge of my seat, waiting to see what would happen to them. It’s a story of a budding relationship during wartime as well as friendship and how violence changes people, but for me, it was a story of shy Rose’s growth. She begins as an innocent girl with low self-esteem, but the ending shows how her night with Eddie has changed her – war has made him look even more fragile, while home has turned her into a woman.

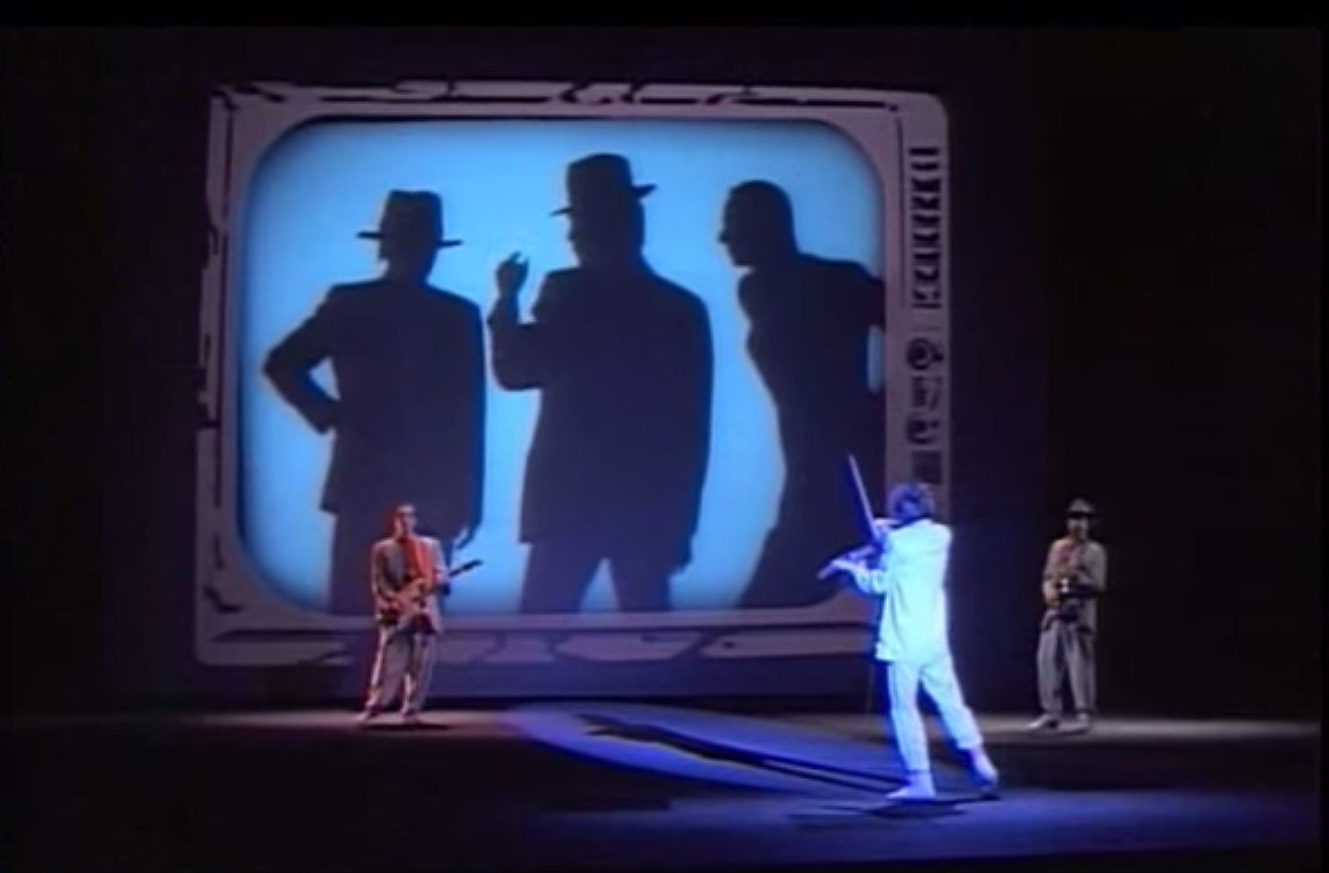

Home of the Brave (Laurie Anderson, 1986)

To be fair, I’d seen Laurie Anderson’s concert film dozens of times as a kid, but this was the first time I’d revisited it as an adult. It’s tempting to call the almost painfully 1980s “dawn of computer technology” style dated, but what Anderson accomplishes still holds up today as a unique feat. Through carefully placed lighting, projected video, and odd costumes, she brings to life a show that is half-song, half-rambling poetic monologue, and all art piece. It’s also funny, and as Anderson jokes with the audience, it breaks away the self-serious attitude that makes a lot of performance art unbearable to me. I can most closely compare her to David Byrne and the Talking Heads, though I’d even say she takes it a step further – a good example is where Byrne had the oversized suit, Anderson had a suit that doubles as a drum machine; in an interlude between songs, she pounds her own body alone on the stage in a jerky dance. Throughout the show, she throws her body around without shame, completely unafraid to reach for musical performance horizons that nobody else could dream of, a showcase of unconventional womanhood, natural and free in her own sense of self.

Miss You Already (Catherine Hardwicke, 2015)

For a two-hour film where almost nothing really happens in the way of plot, Miss You Already covers a whole lot of ground. Jess (Drew Barrymore) and Milly (Toni Collette) meet as tweens and become instant friends. Growing up, they share everything, and are side-by-side for every big moment. In their 20s, Milly gets pregnant and marries a rock star, while Jess marries an oil rig worker and they move into a houseboat. Forward roughly ten years, Milly has two children and Jess has been trying unsuccessfully to have a baby. Milly is diagnosed with breast cancer, and though Jess runs to her side to take care of her, when she finally gets pregnant, she can’t bring herself to share her good news with the physically and emotionally weak Milly. As their situations quickly become tougher, both of their relationships with their husbands get complicated and their friendship becomes strained. Admittedly, Hardwicke’s bizarre direction and editing choices don’t always work – the handheld close-ups and quick editing are messy and awkward as often as they are heartwrenching – but there is plenty of beauty and love in the way she films the two women. What makes this worthwhile is the amazing chemistry between the two leads, and the way they deal with cancer in an unsentimental and funny way. The women are terrified, but they continue to laugh and poke fun at each other just like always, something I can tell you takes great bravery. As dorky as it often is, it’s Hardwicke’s best work in a hugely underrated career.

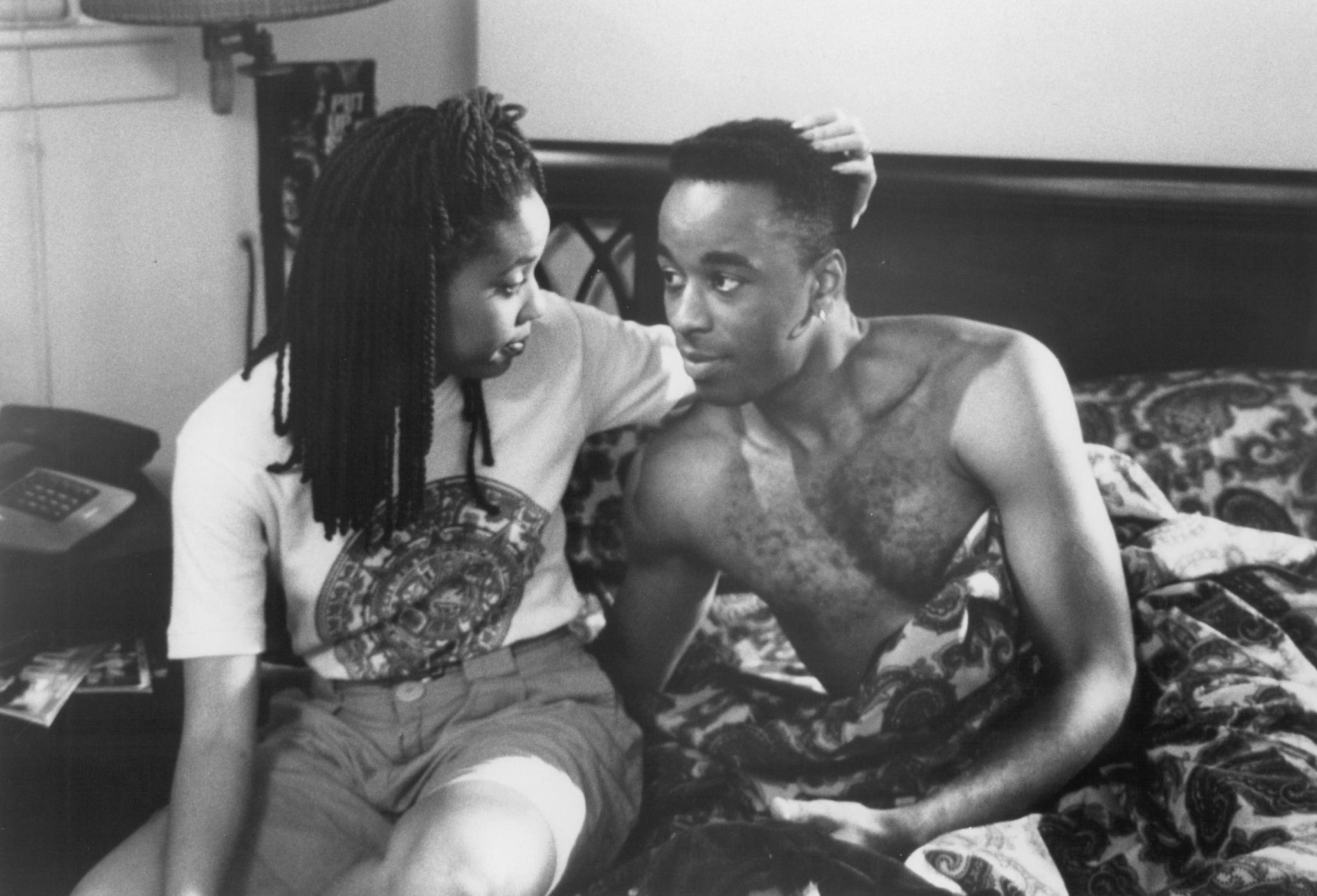

Just Another Girl on the IRT (Leslie Harris, 1992)

This film follows teenager Chantel Mitchell (Ariyan Johnson) as she navigates school, parents, friends, and boys in pre-gentrified Brooklyn. Brash, outspoken, funny, and smart, Chantel is sometimes difficult to like, but impossible not to admire. She refuses to let anything get in the way of her goal to graduate early and go to college, though her stubborn inability to recognize her own immaturity often makes her her own worst enemy. When Chantel gets pregnant, her dream is threatened by the shocking change, and her surprise and confusion almost cripple her. After a few truly shocking scenes in the third act, ultimately Chantel proves to be the young woman many doubted she would turn out to be. The beautifully soft lighting lends the film intimacy while the bright colors of the girls’ clothes make their youth loud and vibrant. Through Chantel, we also see the struggles of her teachers, parents, and friends, rounding the film out so that it could almost be a documentary. It’s an important time capsule of Black culture in 1990s New York, and a still-relevant testament to the resilience of teenagers and the strength it takes to make it through daily life as a woman of color. The scene in which Chantel is in line at the welfare office right after discovering her pregnancy, looking on in terror at a screaming child next to her, is about as real as it gets.

2 thoughts on “The Year in Film, Superlatives (Part 2)”

Pingback: The 25 Best Films of 2016, Part 2 | Movie Mezzanine

Pingback: The 25 Best Films of 2016, Part 1 | Movie Mezzanine