2016 was a landmark year for cinema, because it was truly the worst year ever. That’s what a lot of people on the Internet said: it was the year movies stopped mattering, it was the worst year for summer movies, and it was the worst year—period–for movies. (That last link is particularly bold, its claim being made in February of 2016.) Of course, now that the year is finally, mercifully wrapping up and 2017 is shortly upon us, it’s just as easy to argue that 2016 was one of the best years for movies since the medium began over 100 years ago. Yes, this was the year of Suicide Squad, Trolls, and Independence Day: Resurgence, but it was also the year of Moonlight, Kubo and the Two Strings, Fences, and more. All week long at Movie Mezzanine, our writers and editors will be bidding a fond farewell of the year of film that was 2016. Today and tomorrow, we’ve got superlative categories aplenty in which to award various films, filmmakers, and more, as well as our writers’ picks for the best discoveries of older films that they made in 2016. No more preamble–let’s get to it.

Most Surprising Film: 10 Cloverfield Lane

There are two layers to the notion of surprising regarding 10 Cloverfield Lane. On one hand, did any of us really know anything when its intriguing teaser trailer dropped in early January? Originally titled The Cellar, 10 Cloverfield Lane was very much kept a secret by its producers and cast until just two months before the release of the film. It worried some that this “spiritual sequel” to 2008’s Cloverfield would be yet another sci-fi spin-off monster movie, but what emerged was something quite different. Set almost entirely inside of a bunker, 10 Cloverfield Lane is a genre movie that functions like a tense, living room play. Mary Elizabeth Winstead, John Goodman, and John Gallagher Jr. exchange dialogue steeped in skepticism, leaving the viewer unsure of who, if any, is trustworthy as the three of them hide in a bunker from who knows what outside. Winstead cements her place as a worthy science-fiction heroine, with shades of Ripley as she tunnels through the vents in its climactic fight, and Goodman gives one of the best performances of the year in his turn as a crazy-but-maybe-not-but-also-probably keeper of the keys of their bunker. The whole thing simmers, with not a line wasted, until it bubbles over into a terrifying, riveting climax. A real monster movie to remember. — Fran Hoepfner

Best Discovery of 2016: Female Prisoner Scorpion

Shunya Ito’s Female Prisoner Scorpion films are genius exploitation pictures with a focus on the mindset of women who have suffered unjustly and what that means within the scope of genre cinema. Meiko Kaji plays the evangelical Scorpion, who functions more like a symbolic angel of death in the face of men who are evil to women. She is a powerhouse in these movies, displaying a total performance through stoicism, and body language that hearkens back to the indisputable power of Maria Falconetti’s performance in The Passion of Joan of Arc. The subversion of these pictures lie in Kaji’s iconic performance, Ito’s camerawork, and their genre ties to pinky violence, a subgenre of Japanese exploitation cinema that focused on pornographic representations of women through sex and violence in equal measure.

The Scorpion pictures are frequently shot with expressive, almost theatrical camerawork resembling the works of Seijun Suzuki and Nagisa Oshima, giving it an evolving visual palette that is elegant as much as it is smart. The camerawork shows clear understanding of the power dynamics at hand when addressing sexual assault and gives Kaji’s character and others the space to chart their own path in reckoning with their own lives as they try to move forward. The Female Prisoner Scorpion films do not always provide easy answers or complete resolutions. The outcomes are messy, complicated, and sometimes violent, but the constant in all of these situations is one of communion– that these women understand each other’s plight, different as it may be from woman to woman. Viewing the Female Prisoner Scorpion movies was like a self-exorcism that allowed my own history as a sexual assault victim to be an event I could discuss more openly instead of carrying it silently like a millstone attached to my back. I wasn’t alone. — Willow Maclay

Movie Most Likely to Inspire Future Filmmakers: Moonlight

Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight is many things: Human, compassionate, complex, restrained, modern, sorrowful, beautiful. It’s also hugely influential, or at least it will be in twenty, or ten, or even five years’ time. It isn’t a miracle that Moonlight happens to be great. It’s a miracle that it happens to be at all. Studios don’t make movies like Moonlight. They shy away from them. But we’re living in the #OscarsSoWhite era, when audiences care about diversity in entertainment to the point of demanding it. To describe Moonlight, which Jenkins has been working on since 2013, as a reaction to hashtag backlash would be generous at best, but is it much of a stretch to suggest that his work will encourage other up-and-coming filmmakers – whether black or queer, or both, or neither – to pour themselves into bringing the stories they want to tell to life? Not in the least. As we cross the finish line on the 2016 awards season, and toward the 89th annual Oscar soiree in February 2017, there are many reasons to be excited for the chances of diverse cinema as an awards fixture, Fences and Hidden Figures chief among them. But Moonlight is the best reason to be excited about diverse cinema. It’s the work of a master in the making, and the kind of film that’s primed and ready to spur the directors of tomorrow to raise their own voices. — Andy Crump

Best WTF Editing: Rules Don’t Apply

Warren Beatty’s bizarre Howard Hughes biopic/sex comedy/look at idealism gone sour boasts four credited editors (including Paul Thomas Anderson regular Leslie Jones and Terrence Malick veteran Billy Weber), adding to the narrative that the director didn’t know what kind of movie he wanted to make and wound up with a mess. But there’s a method to Rules‘ madness: Beatty deliberately puts us on edge — often cutting conversations off a beat earlier than expected or abruptly stopping songs just seconds after they start — to give us the same feeling of getting jerked around that Hughes’ employees feel throughout the film. This becomes clearer whenever the film arrives at an extended conversation between Beatty’s Hughes and Lily Collins’ or Alden Ehrenreich’s starry-eyed dreamers, with the director favoring a more relaxed editing scheme that sees his less experienced employees waving off his eccentricities in a way others can’t. By the time the film starts whipping them around again (with Hughes moving his business to new countries, then pulling up the stakes before anyone can drive them in), they’re in too deep, unable to adjust to his inexplicable rhythms but not willing to fully cut ties. It’s a jagged, even radical formal approach that perfectly suits a weird but wonderful film. — Max B. O’Connell

Best Discovery of 2016: Wake in Fright

The vast wasteland of the Australian Outback is a harsh expanse of dire survival. In a 360-degree pan of the region known as Tiboonda, Wake in Fright director Ted Kotcheff establishes a pervasive sense of isolated entrapment, which will remain visually and thematically integral throughout this 1971 Aussie classic. Bathed in a dusty haze, it’s hard to believe life exists out here. For one-room schoolteacher John Grant (Gary Bond), who bides his time before Christmas break waiting for the ticking clock to signal his liberation, perhaps it shouldn’t.

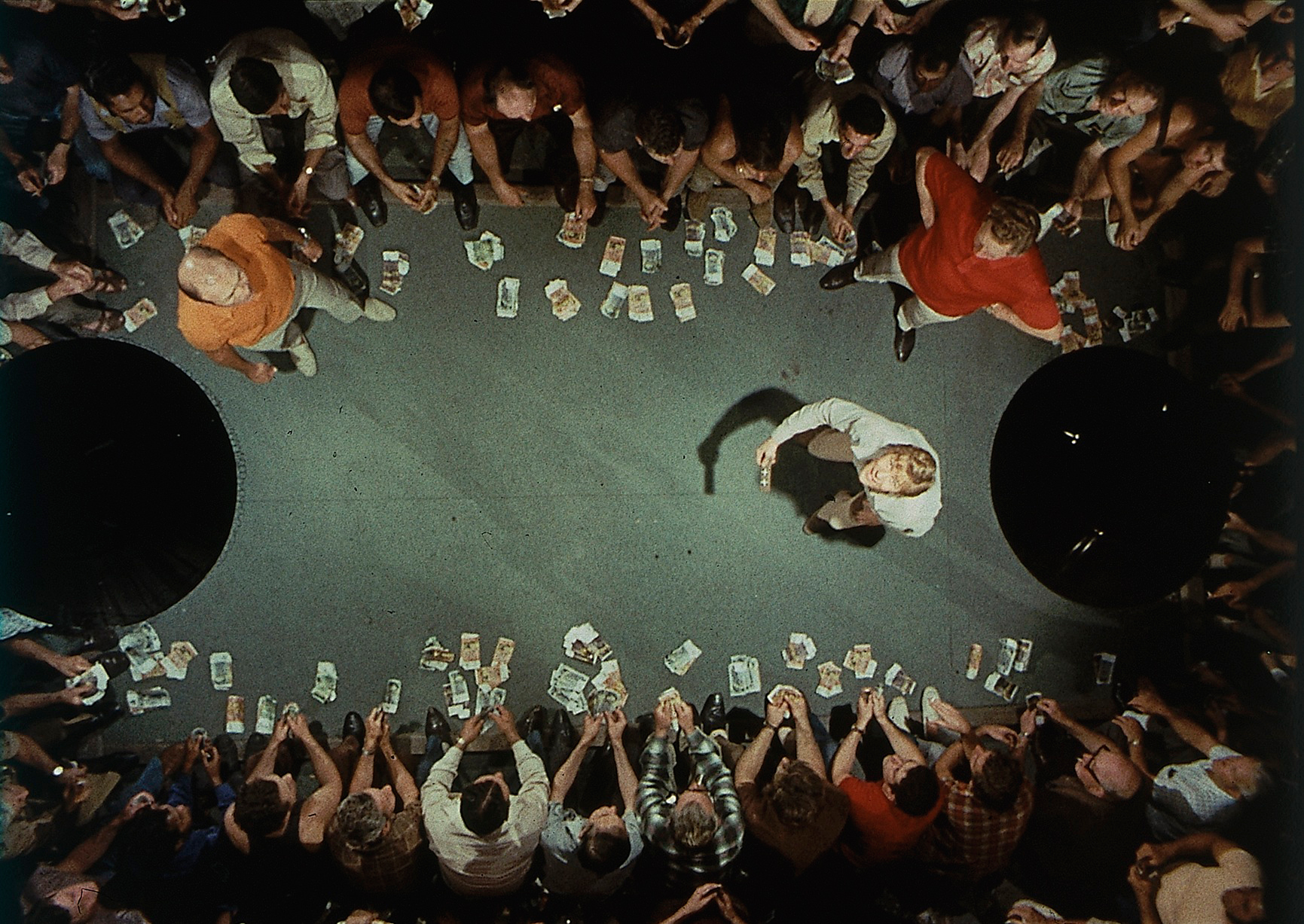

An educated and cultured man, an uppity contrast to the earthy populace, John is assigned to the remote outpost as part of an education department contract, and his disdain for the territory is plainly evident. Before hopping a flight to Sydney, where his beautiful girlfriend awaits, John spends a night in Bundanyabba, known affectionately by its citizenry as the “Yabba,” a boozy burgh where, according to what may be the town’s only cabbie, “Nobody worries who you are or where you come from.” There’s little to do in the area besides drink, so John goes out for a nip and stumbles upon the local gambling pastime of Two-Up. Thoroughly inebriated and ingratiated by lawman Jock Crawford (Chips Rafferty), John senses the wagering potential to secure financial footing and get out of his teaching gig for good. By the sobering light of the next morning, however, the disheveled educator is lying on his bed in a drunken stupor, face down, butt naked, and lacking the requisite airfare.

This initiates the intense, nightmarish thriller that is Wake in Fright, and it signals the dizzying physical and psychological descent of a now-captive John Grant. Life in the Yabba is a seemingly inescapable existence, rowdy and tempting like a beer commercial minus the attractive setting or people. The garrulous townsfolk are pleasant enough, but their demeanor hides an undercurrent of “aggressive hospitality.” While hygiene remains a low priority, the dicey menu of guns and hooch is essential sustenance. John’s chief accomplice is the alcoholic Doc Tydon, played by a captivating Donald Pleasence, who has long since fallen down the rabbit hole of depravity. Now he carouses with the best of them, introducing John to a life of violence, ruin, stifling stagnation treated by cathartic macho bonding, and the horrifying specter of a kangaroo hunt by spotlight. “All the little devils are proud of hell,” Doc muses in a foreboding, self-aware commentary.

John’s initially passive observations blur into a frenetic, subjective tailspin of delusions and inebriated anxiety; his pretty-boy appearance grows grimy, his white clothes assume the soiled hue of flypaper yellow, and arid grit gets plastered to every surface, caked on every sweaty face. Based on Kenneth Cook’s novel, Wake in Fright is a fascinating depiction of self-destruction, madness, and those on the desperate fringes. Lucky to come out of the lost weekend alive, John can only lament: “Oh, I got involved.” — Jeremy Carr

Best Cinematography: Moonlight/Spa Night

Both Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight and Andrew Anh’s Spa Night shimmer. It’s a little cold, or maybe striking, or maybe a chance to move within the waves of light to find yourself. As the title suggests, and from the title of Tarell Alvin McCraney’s original play, in moonlight, black boys look blue. Conversely, burning underneath the sun or scalded by the tungsten glow of a street lamp, black boys look lost. At least in the case of Chiron, who morphs, matures, is molded, and molds over three parts. But while James Laxton’s cinematography allows each part to look distinctive, they’re not disconnected from the whole. Rather, Laxton and Jenkins show how Chiron moves about these colors and spaces and how that changes over time. There is the implication, though, that, as the camera lingers over smoke unfurling from Kevin’s mouth, the boy once so caught by the light of the night has never changed. Spa Night’s Ki Jin Kim makes a Korean bathhouse a smoky, alluring space, but not unlike a scary movie. There’s eroticism there, but dare you go explore it? The wide spaces, the blues and greens that streak the frame, they seem open. As open as you want to be with yourself but can’t be. The lights flicker and sweat beads, but do you want to go into the dark? — Kyle Turner

4 thoughts on “The Year in Film, Superlatives (Part 1)”

Pingback: The Year in Film, Superlatives (Part 2) | Movie Mezzanine

Pingback: Movie Mezzanine’s Year In Film, Superlatives | A Constant Visual Feast

Pingback: The 25 Best Films of 2016, Part 1 | Movie Mezzanine

Pingback: The 25 Best Films of 2016, Part 2 | Movie Mezzanine