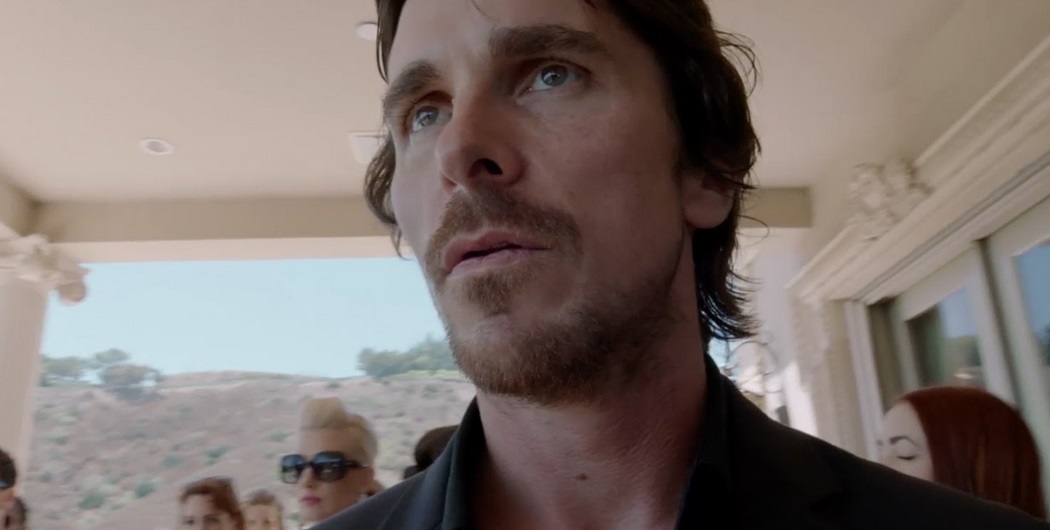

With vacant eyes and mouth agape, man continues his seemingly irrevocable fall from innocence, in Terrence Malick’s eternally juvenile seventh feature Knight of Cups. Christian Bale ambles catatonically through various locales of present-day California as Giorgio Armani-clad Rick, who wakes up one morning during an earthquake and sets off to mourn the death of a brother and acquaint a number of miserable women in strip clubs, dead-end marriages and rooftop pool-sides across the state. There’s no doubt a great deal to be written about this often visually exceptional work—honors, once again, to cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki. But Malick’s latest effort further affirms that he belongs by now in the experimental sidebars of a festival like the Berlinale, so short has he become on the stuff that warrants any messiah-like status.

Though it resurrects some of the autobiographical plot strands of The Tree of Life, it’s the elliptical anti-drama of To the Wonder that this film most resembles. Taking its name from a tarot card, Knight of Cups grabs the epically internalized navel-gazing of the previous film and takes it forward into full-on Malickian throttle. Located somewhere between a self-parodying fever dream and the immature illustrated scribblings of someone wondering why the world is both beautiful and messy in the same moment, this punishingly po-faced tone-poem thinks that in the twenty-first century a great artist can get away with writing lines like, “Be with me, you give me what the world can’t give: mercy, love, peace, joy…” As another character says to Rick: “Tell me something interesting.” Penned by Malick, this has the ring of some suicidal dare.

In fairness, Malick has earned the right by now to do things his own way — and there’s no denying that he does, retreating ahead of the phony imitators who have done their best to discredit his legacy. Once the much-coveted director of only three films between 1973 and 1998, his relatively prolific output of late (three films now in the last half-decade, with more on the sun-kissed horizon to come) has resulted, unfairly or otherwise, in his aesthetic becoming routinized. In the opening ten minutes of Knight of Cups, things appear all too familiar: elegant Steadicam movements meld with jump-cuts to suggest a transitory atmosphere, a reality difficult to pin down, narrated with chips and nuggets of pseudo-poetic meaning (“fragments, pieces”) in disembodied voiceover—all of which compete for one’s attention with the gorgeous and eclectic soundtrack.

Wes Bentley appears as Russ, Rick’s brother, and Brian Dennehy—a joy to watch even in those unfortunate TV movies he’s all too often agreed to do—plays their father. In scenes overwhelmed with a sense of melancholy, the three of them mourn the loss of the third sibling, Billy. It’s in reaction to this that Rick seemingly plunges himself into a world of empty seductions and shaven pussy. “I see how you look at me,” says one such fling. “You think I could make you crazy.” A sex scene ensues, its gloominess connoted by Bale morosely buttoning up his shirt afterwards; his flame’s mascara is heavily smudged. Later, we learn, either in flashback or as a present-day subplot (working with three editors, Malick sends his tenses on triple orbits of collision) that Rick has an estranged wife (Cate Blanchett). Later still, he embarks upon an affair with an unhappily married waif (Natalie Portman).

Everything is connotation here. Latter-day Malick is a master of visual approximation, with seemingly little interest in the depiction of things in and of themselves. On the few occasions where the director encounters what are presumably non-actors, such as poverty-stricken people living on sidewalks, or heroin addicts with alarmingly swollen legs, the film comes to life with the vibrancy of artistic hazard. Too often, however, we’re stuck with Bale walking around abandoned ruins and the half-constructed buildings of a late capitalist nightmare. An empty but fully-erected town on a Hollywood backlot suggests some self-reflexivity at work, while the scaled-down simulacrum of an entire city centre, replete with moving traffic, further heightens the Baudrillardian sheen.

Indeed, Malick takes the kind of dramatic displacement that he so dangerously let free in To the Wonder to another level entirely here, dragging what scant storyline there is by the scruff of its reluctant neck, capturing some startling images along the way as he allows platonic ideals to stand in for the real thing. Beautiful women on balconies and on beaches; a self-suffering protagonist; declining marriages and tension-fuelled familial relationships. As one character claims late on in this folly, “no one cares about reality anymore.” The obvious refrain to which, of course, is “speak for yourself.”

2 thoughts on “Berlinale: “Knight of Cups””

just two minor footnotes which, at least “speaking for myself”, more than adequately serve to deconstruct your supposed reading.

1 – if you really doubt that “no one cares about reality anymore”, then you’ve betrayed your (relatively advanced) age. have you tried going outside (your own head, I mean : P )?

2 – you really don’t know your Heidegger, do you? : ) to watch Malick without having at least a ‘idiot’s guide to’ grasp of Heidegger is a waste of your, and your readers’, time.

for Heidegger, there are no “things in and of themselves”!! reality is what we think reality is, which is not even close to saying that it’s all a BS dream anyway. & if you don’t know the difference between the former and the latter, you’ll never understand how two people can disagree about an experience they both witnessed at first hand, hell, you’ll never understand people period.

Pingback: Looking Closer at Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups | Looking Closer with Jeffrey Overstreet