To give you a sense of how I feel about Valentine’s Day, I’ll share two short stories. First, a couple years ago, I had a “platonic” Valentine, for whom I prepared Hershey kisses by removing the paper tags in each and replaced them with various lyrics from Elton John’s “Your Song.” And then last year, for Valentine’s Day, I attended a double feature at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts of Lars von Trier’s Dogville and Manderlay. Alone. It was sublime. So it might be fair to call me a romantic cynic, which my therapist explained makes sense given my gravitation towards bleak Scandinavian or French art films and bittersweet British romantic comedies. The intersection of these two aesthetic sensibilities and a good descriptor of what a “romantic cynic” would is a single word: masochist. I do adore sitting around in my sweats, stuffing my face with chocolate and pasta, and watching The Piano Teacher and Bridget Jones’s Diary. I’m all for projecting my unfulfilled desires onto movie screens, as many cinephiles do. If you are like me — single and possessing a penchant for self-deprecation — and probably have been listening to Whitney Houston’s “I Wanna Dance with Somebody” on a loop for the last few weeks, here are a few recommendations for masochist in you:

Weekend (2011) | Directed by Andrew Haigh

Occasionally described as a gay Brief Encounter, I’m inclined to argue that Haigh’s film is more powerful. Perhaps it’s because I’m queer myself and enjoy weeping into a bowl of ice cream when I watch this film, but the social ramifications between heterosexual adultery in the 1940s and queerness in the 2010s seems more heartbreaking in the latter. It’s only ever hinted at in Weekend, but Tom Cullen’s Russell hints at an internalized self-shame, perhaps even an internalized homophobia. He’s even disinclined to share his love life with his straight best friend. But in the heat of the moment, in a ostensibly meaningless hookup with boho chic artist Glen (Chris New), he projects what he wants to be and whom he wants the other person to be in this scenario. As Glen’s art project—in which he records a series of questions and answers the morning after an overnight hookup—suggests, these brief moments are in themselves more revealing than even prolonged time together. Weekend is arguably exemplary of the contemporary queer film: it revels in the specificity of the queer experience, but it takes on universality when articulating the power and meaning behind a moment, any moment.

Antichrist (2009) | Directed by Lars von Trier

For you sadomasochists out there, this is like Don’t Look Now by way of Tarkovsky, a film that finds pleasure in visceral reactions. Its emotional weight and clinical analysis of depression notwithstanding—the main plot revolves around a married couple going into the woods after their child dies—von Trier formally channels the pain, anxiety, and fear. He accomplishes this via dark spaces, slow-motion sequences, Freudian-askew frames, and digital photography that appears as if pastels were introduced into Francis Bacon’s harrowing artwork. That anxiety is articulated explicitly and the camera inhabits that helplessness, particularly in a scene where She (Charlotte Gainsbourg) describes her symptoms. Every frame is a manifestation of that kind of fear, but it’s rendered beautiful. Not unlike Trevor Link’s assertion that Melancholia makes depression palatable in a self-actualization sense, Antichrist does a similar thing, but with more grit and horror, while also commenting on the vacillating push-and-pull of a marriage thrown into disarray. And let’s not forget genital mutilation! There’s nothing sexier for an anti-Valentine’s Day movie marathon than that, and also foxes that shout growl “chaos reigns.”

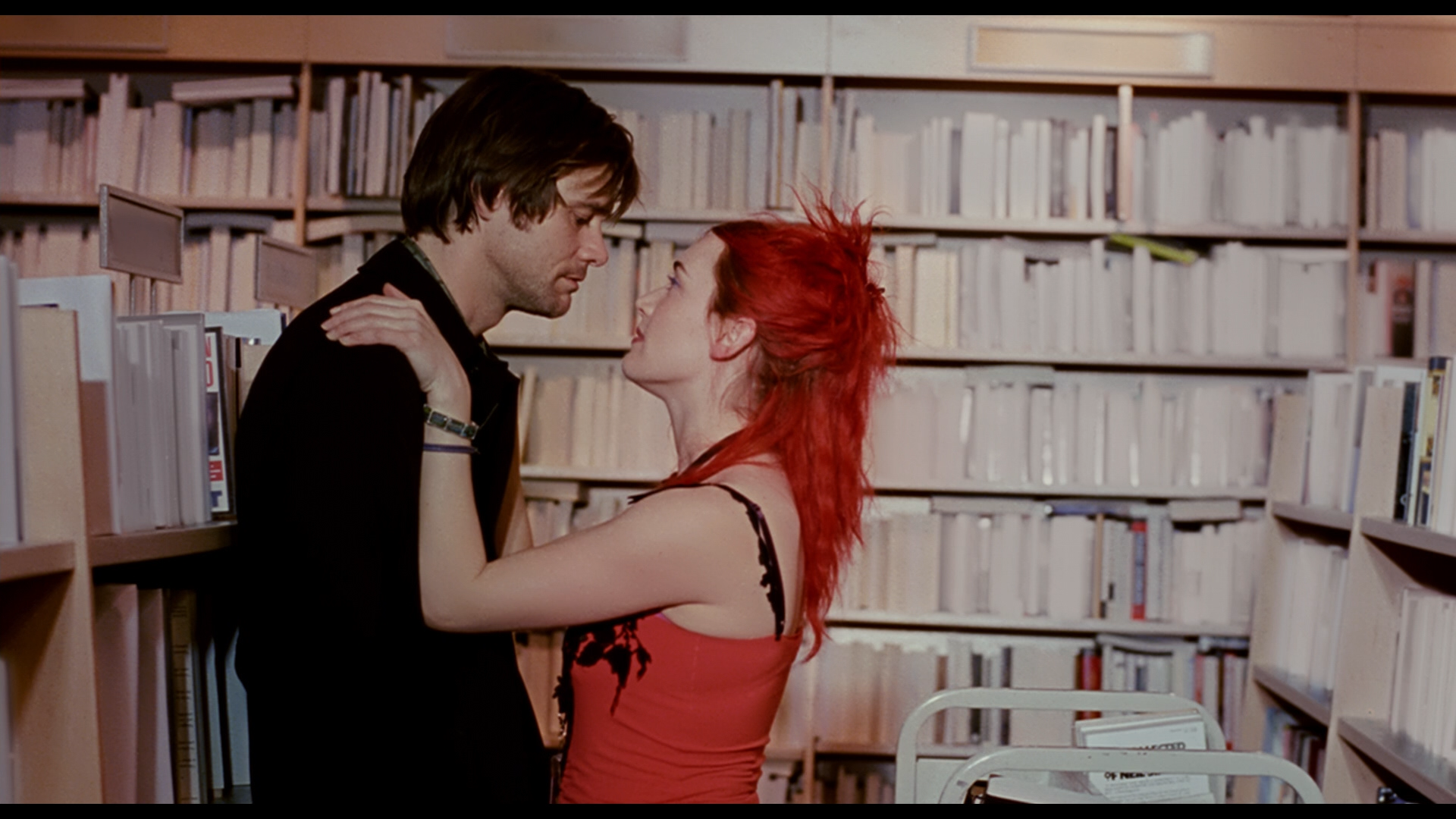

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) | Directed by Michel Gondry

What is at the heart of writer Charlie Kaufman and director Michel Gondry’s sci-fi-ish romance? Is it that people never change? That we’re doomed to repeat our same mistakes over and over again? Yeah, pretty much. There’s still something intrinsic to Clementine (Kate Winslet) and Joel’s (Jim Carrey) being that make them attracted to one another, and yet test the patience of compatibility over time. Despite its passionate underpinnings, Eternal Sunshine is essentially about how futile romantic love is. Despite the fact that their memories have been erased and they keep going back to one another, the two will always find themselves detesting the other, and fighting and shouting. What’s the point then? What’s the point in that arduous journey and quest for something that ends up breaking our hearts each time, making us seek out something like Lacuna? Neither Gondry nor Kaufman are so presumptuous to offer an answer as to why this is, and so we’re left with an ambiguous ending, the viewer then tasked with offering an answer. Perhaps, taking a page from Woody Allen’s bittersweet capper to Annie Hall, we’re all in it for the eggs.

In the Mood for Love (2000) | Directed by Wong Kar-Wai

It could be argued that Wong Kar-Wai’s romantic drama is more typical of a good pro-Valentine’s Day list, but, as with the previous entry, I do wonder if this is not a misreading on the part of movie marketers and eternal optimists. Luscious, and practically exuding sexiness on screen, it’s not hard to understand why it’d be on such a list. But, ultimately, it’s a film about romantic repression, with passion transposed onto succulent and near-silent meals between two people (Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung) who discover their respective spouses are cheating on them. But the core of the film is about unfulfilled passion between two people who are almost too polite to act upon perpetuating the infidelity that reets them. Therefore, their love is never consummated. The tension fills the air as smoke unfurls from Leung’s cigarette and “Yumeji’s Theme” echoes down the halls. Shot decadently by Christopher Doyle, it’s an anti-Valentine’s Day film because it’s about two people who eat their feelings too.

The Heart Machine (2014) | Directed by Zachary Wigon

Billed as almost an anti-Her, in which one man (John Gallagher, Jr.) is in a relationship with someone through a computer (Kate Lynn Sheil). Zachary Wigon’s Skype-filled film is far more painful and touching than Jonze’s Oscar-winning sci-fi romance. There’s an inherent cynicism to the film’s isolated twosome that appears to be a primary selling point, appearing to comment on Her’s intangible relationship premise. But while the two films may be positioned at opposite ends of the spectrum, The Heart Machine eventually works its way to the middle of dashed hopes. To its advantage, Wigon’s film isn’t tripped up by saccharine sentiments, and thus allows itself to ask certain questions more directly about authenticity, idealized affection, relationships, and what love means today with so many technologies mediating our experiences of connectivity. Although there’s a prickly edge to it which is reminiscent of The Conversation, it’s as heartbreaking as one could ever want.

One thought on “The Single Cinephile’s Guide to Anti-Valentine’s Day Films”

Eyes Wide Shut?