Alexander Payne’s last three movies have been about despondent men trying – and failing, mostly – to connect emotionally with the people around them. His latest, Nebraska, is about two such men learning that they should try to connect to each other. It’s the filmmaker’s most reserved picture yet, miles away from the acidic screwball comedies that made his name. He’s no longer a satirist – he looks at his characters head-on, instead of from up on high.

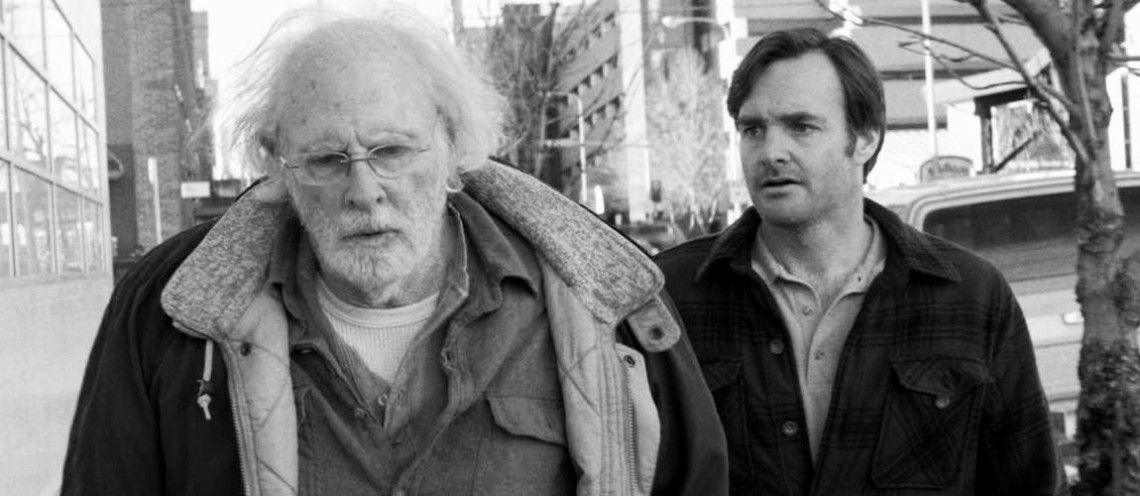

Bruce Dern and Will Forte feature as the two, a Midwestern father and son, both struggling with the opportunities life has decided to hand to them. When the film opens, Woody Grant (Dern) is wandering the roads of his hometown, away from his nagging wife, away from the disappointments of old age, hoping to reach the titular state so he can cash in a Publisher’s Clearing House-type letter that suggests he’s won a million dollars. Usually, he’s returned to his house by neighbors, assumed to be in the thralls of dementia. He’s old-school masculinity in every way: he went to war, he brags about how he “pays his taxes,” he cares about nothing more than his truck, he speaks lovingly about how his father would let him sip beers at age 6. He’s also an unrepentant drunk.

David Grant (Forte,) alternatively, is working a retail job selling stereo equipment, and was recently dumped by his girlfriend. He’s meek, understated, and seems permanently anxious. The primary character detail that Payne affords him is the fact that he doesn’t bother to water the plants strewn about his thoroughly unspectacular apartment. So when he agrees to drive his Dad to Lincoln to see, in-person, if there’s one million dollars waiting for him, it doesn’t feel like a moment of decisiveness. Instead, Forte plays it like his father’s desires have beaten him down, like it’s the path of least resistance – his character’s preferred mode of living.

The two men’s trip to Lincoln takes a pit-stop in Hawthorne, Nebraska, where the elder Grant grew up. His meeting with his family is painfully and thoroughly unsentimental: they spend their first day together in many years watching baseball and discussing how long they spent driving in order to arrive. (The auto-obsession is a clear motif; one of Woody’s relatives likes to station his lawn chair out by the road, wasting his days away watching cars drive by.) Woody settles into the rhythm relatively quickly; David, alternatively, couldn’t look more out-of-place stationed on a cheap couch with a cheaper beer in-hand. This is the flip-side, Payne suggests, of old-world machismo: a whole generation of men interested in nothing other than cars, sports, and beer.

In Payne’s early days, he would’ve milked the contrast between these two standards of masculinity – between the stoic war veteran and the anxious millennial, between pre-70s machismo and the meek modern man – for humor. However, he’s come to a point in his career where he’s satisfied to merely observe, rather than poke fun. He’s not out to laugh at caricatures, his aim is now more focused on allegory.

Gone is the heightened reality and karmic balances that governed the universes presented by his Election and Citizen Ruth. Nebraska takes place worlds away from such realities: in a world of stark black-and-white long shots; a world that proceeds at a leisurely pace; a world that chooses to observe its characters rather than judge them. This is more of a melancholic reverie than a young man’s outburst – this once-furious auteur has grown up, and mellowed out.

The points of reference are easy to parse out: the film opens with the New Hollywood-era Paramount logo, and Payne’s oft-cited Ozu fandom makes perfect sense under the light of a black-and-white picture studying the generational divide among family members. Yet the director is not overly indebted to the cinematic generation that produced Dern, or to his own directorial inspirations.

He’s a native Nebraskan himself, and so the observations made about his cast of characters – the way families uses their rare time-together to collectively watch television, the overly friendly way in which people insult and cajole each other, and the overriding male interest in beer and cars – feel ripped from personal experience. His film is not a feature-length homage to eras and movies past, but quite acutely about contemporary conflicts and relationships.

One scene, watching the father and son swig beers together at a Hawthorne bar, dramatizes the difference between the two men quite clearly. Dern swigs bottle after bottle, not paying a single thought toward his son’s concern. Forte, resolutely sober but extensively nagged by his father, joins in against his own wishes. “You do what you want to do, and so do I,” Dern later says, justifying his late-in-life drunkenness.

Indeed, he thinks that he does whatever he wants, but the truth is that neither of them do. The elder man’s decisions were made for him by a society that thrived on archetypes and obedience and craftsmanship, and the younger, who’s never experienced such a world, lacks the self-agency needed to make decisions for himself. Forte’s in a state of arrested development. Dern, decades past his marriage’s bright years and his war experience and his career, with nothing left to look forward to than baseball games and trucks and beers, can’t help but regret the utter banality of what he spent a lifetime developing.

And so they both make their way through Nebraska – looking at their old homes, old cars, old roads – contemplating the lives that have landed in their laps, as if they were crafted without their own input. There’s a stunning conversation, at that same bar, where the two talk about all the things they never bothered to talk about before: about love, marriage, lost paths in life. Dern’s life came and went in a snap – he says, with defeat in his voice, that if he hadn’t married his wife he would’ve just “ended up with someone else who would give me [the same] shit.” He then elaborates: “back then, divorce was a sin.” He thinks it’s the rules that changed, when it’s actually the people, and the culture. Forte is the next generation, and instead of having these decisions made for him – get married, buy a car, go to war – he hasn’t made any at all.

They’re both realizing that when they reach the end, there won’t be a million dollar prize waiting for them. There will only be these decisions they’ve made, the relationships they fostered, and the results those things produce. Payne’s primary visual motif here is a long-shot of a road, with our characters traveling down it, mere dots on a wide-ranging landscape, coming and going without ever changing their surroundings. To be blunt, it’s how he represents their paths through life. What our characters learn, slowly but surely, is that the road isn’t what they care about at all – what matters is the other people populating it.

2 thoughts on “Alexander Payne Takes A More Observational Approach in ‘Nebraska’”

Pingback: The Travels of Alexander Payne | Movie Mezzanine

Pingback: BOFCA REVIEW ROUNDUP 11/29 | Boston Online Film Critics Association