Editor’s note: Today we’re proud to present readers with an exclusive passage from Peter Labuza’s upcoming book Approaching the End: Imagining Apocalypse in American Film. Be sure to pick up the book up when it comes out next week, October 14, from The Critical Press.

While I’ve always cautioned myself against films that simply decry the so-called evils of technology, They Live uses technological progress to expose certain issues inherent to society. If science fiction is often viewed as a Utopian/dystopian dichotomy, the “happy” ending of John Carpenter’s film is more ambiguous—a past order has been disassembled, but annihilation now hangs in the background. It is something to both celebrate and fear.

They Live broadens noir’s influence on the apocalyptic narrative by presenting a vision of a destructive society created by otherworldly creatures. However, these outsiders only destroy society from within by exploiting its inherent problems, via a critique of the Reagan-era vision of class. As Frank tells Nada about his version of the golden rule, “He who has the gold makes the rules.” The film seems lackadaisical in its panic, which itself becomes its own subversive statement against the status quo.

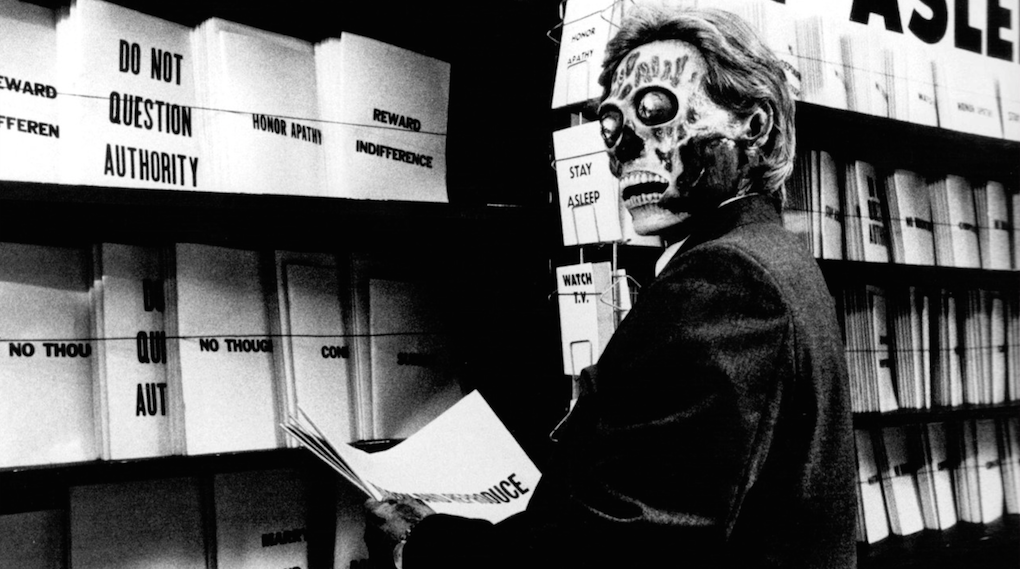

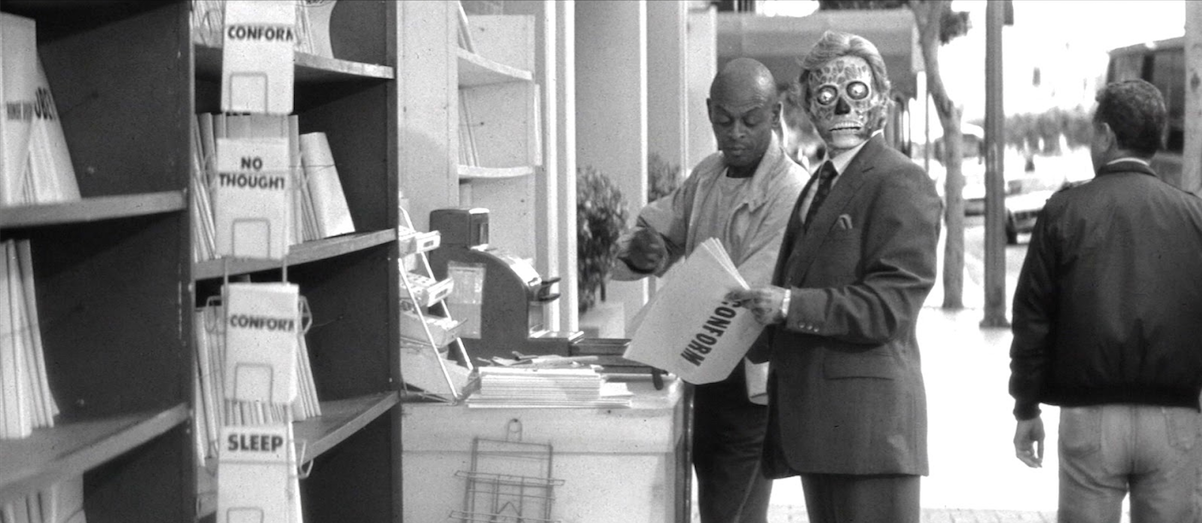

While the politics of They Live are hardly profound, the film cleverly and spiritedly depicts these divisions with a tongue-in-cheek attitude in line with most of Carpenter’s films. The film’s “surface” genre would be science fiction, as Nada discovers about halfway through the film that the “haves” of this haves-and-have-nots society are actually grotesque aliens, while every billboard and magazine is filled with subliminal messages that read OBEY, CONSUME, WATCH TV, and CONFORM. The film makes its critique of Reagan explicit by having an alien politician talk about “Morning in America” on television, as well as mocking culture moralists with the alien complaining about violence in contemporary cinema. Before this reveal, Nada is simply an underprivileged member of society, almost denied his job because of his lack of union credentials, as well as pay for his construction work. His society is oppressive without reason. Helicopters dominate the sky and police raze an urban community (appropriately named Justiceville) to the ground without explanation, paving the way for who knows exactly what.

There is a question of why They Live might constitute an apocalyptic narrative as opposed to other films about a similarly “blind” society, like The Matrix (Wachowskis, 1999), especially given that the visual palette of the latter recalls cyberpunk. There are a few specifics, however, that would classify They Live as a much more appropriate example. Firstly, while both They Live and The Matrix present what could be considered dystopic societies, They Live is actually a portrayal of contemporary society but with an “explanation”; The Matrix reveals a postapocalyptic society beyond what is merely seen. Secondly, The Matrix’s narrative, as many have noted, is a Messiah myth, which has a melodramatic structure, wherein good and evil are very clearly delineated. While there is a very famous “choice” in the film (red pill or blue pill?), this is a choice that leads to the protagonist’s redemption, not destruction. In They Live, the film’s structure is more anarchic and set toward defiance; Nada is not righting society’s wrongs so much as upending it. He holds up a bank by declaring, “I’m here to chew bubblegum and kick ass . . . and I’m all out of bubblegum,” and his final moment is to explicitly point a middle finger right at the camera. In fact, the aliens who have taken over society have done nothing to cause the apocalypse—it is Nada and Frank who cause the end of the world, in deciding to expose the truth by destroying the satellite and cause all-out chaos.

Noir structures are also in line with Carpenter’s work as a filmmaker, even if his tone at times achieves Tashlinesque levels of irrelevant humor. But part of this is his own image of a filmmaker trying to find something to laugh at in a world almost entirely consumed by evil. Kent Jones writes: “For Carpenter, evil is horrifying enough even if it’s outside of us; his characters never court evil, but simply recognize it, which is the moment of absolute horror. His films are filled with moments of paralyzing immobility, of dry-mouthed discomfort brought about by the realization that there is something new and awful in the world.” There is no innocence in his films-his vision of Howard Hawks’s The Thing from 1982 essentially upends Hawks’s notion of a community dynamic building together by creating one that literally tears itself apart. The image of New York City in Escape from New York shows the entire metropolis as one vast prison system, created out of convenience to contain evil instead of actually confronting it. There’s always an odd line between the system and looking to its aberrations to redeem it—those willing to break the rules (Ice Cube’s acknowledgement of the camera in the final shot of his maligned Ghosts of Mars feels like his own subversive statement) are the only ones who can truly change society. Carpenter’s films never end with redemption of the issues at the heart of society—they turn explosive and often inward, driving their own madness to the extreme (an image made literal in the final moments of his 1994 films In the Mouth of Madness, where Sam Neil can only laugh at the sight of his own failures). In They Live, there’s a certain “fuck-it” attitude that seems unique to Carpenter, an irascibly funny guy who’s given up on searching for solutions—truly a noir dynamic if there ever was one.

Frank Armitage (Keith David) initially suggests good luck will come to those who wait. But the American dream is literally rigged in They Live, leading toward the “destruction of the sleeping middle class” as the illegal television stream Nada watches explains. If film noir is all about characters realizing their society has displaced them as outsiders beyond their means, They Live is the film that openly reveals the source for such an anxiety. The aliens have used technology not to destroy society but only to exploit its already inherit differences, accelerating and exacerbating these problems. It is noteworthy that the film’s acclaimed sunglasses vision is specifically in black and white and set in an urban sprawl, directly recalling film noir. The grotesque creature design, and the small UFOs that fly around, play on tropes of B-movies of the 1950s as well—like Kiss Me Deadly, it combines the high culture of the rich with a grotesque low culture. By seeing the world in “Noir-o-Vision,” Nada sees the injustice he lives in, and thus responds with his noir-like defiance. The glasses themselves become representative of the temporal dislocation; the glasses are a futuristic work of manufacturing, taking the viewer back to a past palette, which represents a more truthful vision of society.

The film jumps from genre to genre—Western, Grapes of Wrath-style poverty drama, a six-minute pro-wrestling-style fight (or a joke of one), and finally an action movie’s blow-’em-to-hell narrative. But underlying this is a modal structure of noir and its apocalyptic narrative, where the dislocation of past innocence as a lie (the aliens tell Nada they’ve been around since the 1950s), and thus defiance through creating the apocalypse is the only route out. While not about the coming end of days, Evan Calder Williams notes that They Live plays a second type of apocalyptic narrative, where “the revelation is a clarification along the lines of krises (separation/ judgement), allowing you to know where good and evil stand . . . [They Live is] suddenly seeing what ‘was there all along.’ “Holly tells Nada “You can’t win,” so his journey is not about the return to innocence, but one of epistemology, of exposing the knowledge he possesses. The film’s lengthy wrestling fight between Nada and Frank is based on one fact only: that Frank must see and know. Carpenter indulges in portraying the most prolonged, hyper-masculine, grotesque violence to the point of parody in order to achieve this goal. Nada commits the most intense, violent harm to his only friend all in the service of destroying Frank’s innocence.

There is no stopping the alien force, but there is a new apocalypse in exposing them, as shown in the film’s final, darkly comic moments. Nada himself has no place of innocence that he could return to. Played by wrestler Roddy Piper, Nada is the epitome of 1980s machoism taken to an extreme, and while he originally declares that he “believes in America,” the film makes him into a disillusioned enemy of the state who instead must destroy the country he loves. In a confession to Frank, Nada explains how he ran away from home because his father beat him, suggesting that perhaps this idea of a perfect “Morning in America” was always a lie. He concludes, “I ain’t daddy’s little boy no more.” They see only one way forward—onward with the apocalypse, and do it in style. “Hey, baby, what’s wrong?” an alien asks his human girlfriend in the final shot, followed by a sudden cut to the credits. We have no idea what the next day of this society will look like—if one had to guess, a nuclear holocaust or the enslavement of the entire human race. In the cinema of John Carpenter, the apocalypse is a better way out than living “between the white lines,” which Nada calls “the most boring place to drive.” Like Kiss Me Deadly, Carpenter has more than a little fun with They Live’s destructive sequences, embracing noir’s aberrations of society to defy truly aberrant characters in a riposte to the status quo of Reagan’s America.

2 thoughts on ““They Live” and Apocalyptic Tech Noir”

Pingback: Movie Mezzanine RSS Feed

I am glad to see They Live receiving the critical academic writing is deserves. This is one of my favorite films, and one of my favorite John Carpenter films as well. When I watched the fight/wrestling scene as a kid, I thought it was an obvious nod to Roddy

Piper’s wrestling career, but a deeper analysis would tell another tale. If you look at the scene from the point of view of waking up someone who actively decides to “stay asleep”, then the over the top violence in the scene makes complete sense. Some people would rather live ignorantly in bliss than have to confront the horror of reality and admit to being duped all their life. Excellent analysis. I will definitely check out your book.