Alex Gibney’s Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine captures the titular Silicon Valley titan as a genius with questionable morals at best. During Jobs’ lifetime, his virtuosic output was front and center and the public overlooked, say, the fact that Apple put a stop to its philanthropic activities under the co-founder’s leadership. On one hand, most consumers cared about their money’s footprint, but also happily upgraded to the new iPhone model as soon as they could. With The Man in the Machine, prolific director Gibney delivers a thorough, yet overlong and formulaic (utilizing the conventional equation of talking heads + voiceover + archive footage), documentary of contradictions. Gibney wants us to turn the mirror on our Apple-toting selves—and when he manages to inspire this, the resulting realization is quite unsettling. However, one wishes Gibney would’ve pushed his agenda further without getting sidetracked by his own admiration of the Apple world.

The personal computer pioneer Steve Jobs undoubtedly turned Apple into a cult of sorts through sleek and user-friendly products. Since its “second coming” starting with the iPod—and becoming unshakeable with the iPhone in later years—Apple now seems like the default, no-brainer option in a market that has no shortage of alternatives with more reasonable price points. When Jobs passed away in October 2011 due to cancer—basically, the starting point of Gibney’s archival mash-ups—the world of Apple devotees mourned in tears and with #iSad hashtags. Candles, letters, and flowers were left in front of Apple stores worldwide. But for a man who was neither a rock star nor an influential political figure, what ignited this kind of a universal response? And why was it so convenient for Apple loyalists to ignore Jobs’ dark side that resulted in a legacy littered with poor ethical choices?

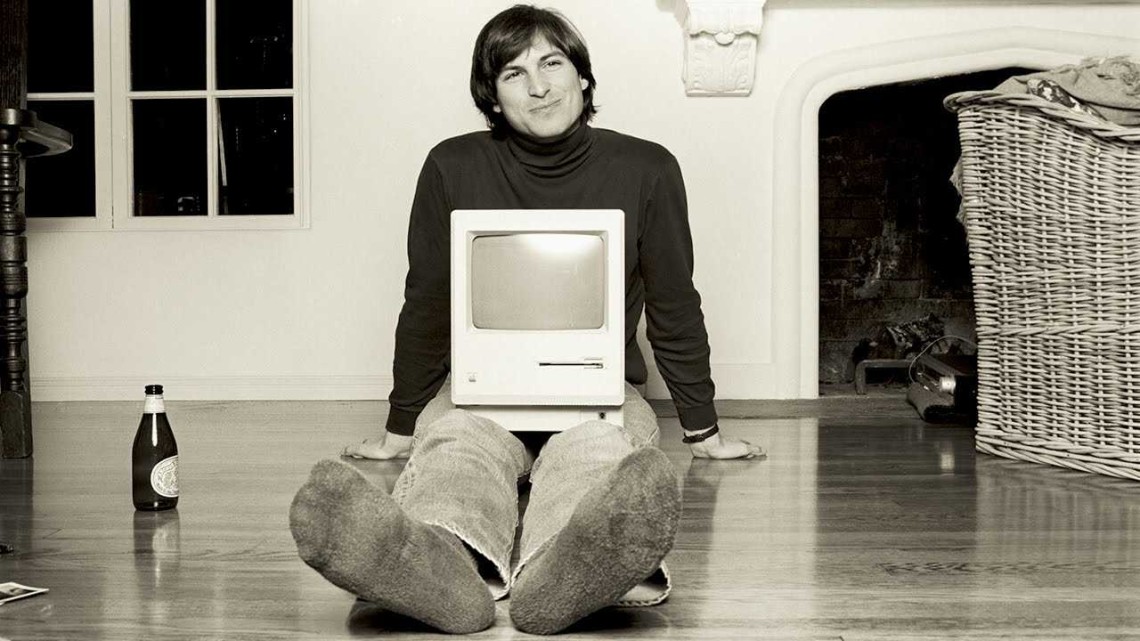

Alex Gibney doesn’t have any of the answers. Yet only shortly after taking on the Church of Scientology in Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief, he aptly chooses to treat Apple as the cult it is and sets off on his path in search of revelations. Alas, nothing in The Man in the Machine is particularly a surprise or a major exposé. Jumping back in time from Jobs’ passing and going in chronological order afterwards, Gibney starts from the ’70s and establishes Jobs’ knack of disrupting the status quo with the story of him and his partner Steve Wozniak introducing a phone hack device that allows its users to make free phone calls anywhere in the world. Then Gibney follows suit, listing accomplishment after accomplishment for Jobs until his departure from Apple in the 80s and its unstoppable boom upon his return in later years.

But beyond the respect Gibney pays (the imbalance of which once again confuses the doc’s POV and agenda), the portrait of Jobs is hardly flattering, and even unflinching at times. A myriad of ex-Apple employees talk anecdotally about the man, along with what he and Apple cost them—sometimes time with family and sometimes basic sanity. Yet the most gut-wrenching part gets delivered through an interview with Chrisann Brennan, the mother of Jobs’ first child. Jobs had denied his paternal relations, but after a test proved otherwise, he agreed to pay $500 a month in child support. At that time, he was reportedly worth over $200 million. The film also includes references to the Foxconn scandal, of employees committing suicide in the face of Apple’s harsh deadlines and low pay, and how Jobs never cared to take the necessary steps to address human crises.

Nonetheless, The Man in the Machine often feels and plays more like a glorified table of contents for an icon than a stable and focused film. But to its credit, it accomplishes something greater than exposing the dirty hands of Apple—it makes the viewer briefly cringe in guilt. Perhaps Gibney never cracks the code to why millions religiously worship Apple and its co-founder despite all. But maybe the answer is a lot simpler than it initially looks. In his jeans and black turtleneck, Jobs tapped into the pathetically narcissistic traits of humanity and legitimized them. He wrapped us up in a chic box and gifted ourselves back to us. He helped connect us to the rest of world at the expense of our immediate, “in the moment” experiences.

One kid at the beginning of the film lists all the i-Things Jobs made. At the end, he says, “he made everything.” And in that—as well as many other kids’ worlds—the distractions that fit in the palm of a hand are indeed everything and the awareness of systemic isolation may be lost on a younger generation. And that is perhaps the realest of all of Jobs’ legacies.