Shelf Life is a weekly feature that selects a film currently on DVD/Blu-Ray for review.

Mel Stuart’s 1973 documentary. Wattstax simultaneously fits in and radically contrasts with concert films of the previous few years. Monterey Pop and Woodstock showcase political bands making political messages for a disenfranchised crowd of youth not yet given legitimacy in politics by the 26th Amendment. Wattstax, too, uses music to give voice to the unheeded, in this case the predominantly black Watts district of L.A. which sent ripples through the country in 1965 with a massive riot that laid bare the racial tensions that simmered in all states, not just the Deep South.

Jimi Hendrix warped the “Star-Spangled Banner” through a wah-wah pedal and thrilled a crowd, but when Kim Weston starts Wattstax with a rendition of the National Anthem, the audience barely stirs. Then Jesse Jackson introduces her next song, “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” by its alternative title, the Black National Anthem. As she sings this song, the crowd stands and fists rise in solidarity. In an instant, the viewer can see just how far outside the Establishment some people lived.

Wattstax potentially suffers from a lack of concert footage. Yet Stuart spins his dissatisfaction with that material into a boon by filling the gaps with clips of the surrounding area and interviews with residents and activists. The talking heads clash with the uplifting gospel, pouring out anger that still roils nearly a decade later as conditions remain as they were before the riots. (Ted Lange, of later Love Boat fame as the perennially smiling Isaac, is virtually unrecognizable here for the righteous fury in his voice as he discusses social ills affecting Black America.) The dropout youth of the ‘60s wanted to remake the country, but the people of Watts and those who come for the festival seem to know they will always be at odds with this country.

The music of the festival, along with the clips of Richard Pryor convivially telling jokes at a bar stool for some locals, serves less to be a political catalyst than a release valve. The lineup Stax assembles for the concert plays like a condensed history of African-American musical expression: gospel and blues morph into soul and R&B, before some blasts of funk bring the evolution to the present. The rock embedded in the late-’60s scene is all about the present, about new sounds, new states of mind, but Wattstax is etched in a rich history of music as the only voice granted to the disenfranchised.

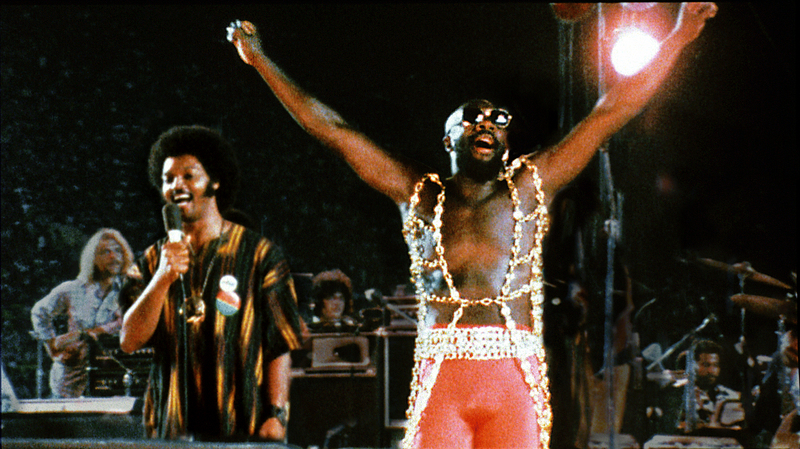

This confluence of social history and artistic escape climaxes in the closing act: Isaac Hayes, who triumphantly throws off a cape to reveal a rudimentary vest made of gold chains. The getup plays on slave imagery, then explodes it through sheer force of presence: this is not an oppressed man bound by shackles but an armored warrior ready to do battle. Like the gospel and blues lying under all of the music played at the festival, Hayes’ image flips suppression into expression, and the charge sent through the crowd is as thrilling as any of the great tunes played throughout.

Wattstax may not be an ideal display of the rich, deep wells of talent the Memphis label had to offer, but it excels as a document of a people whose rooted but always growing musical repertoire is indicative of their social struggles. Compared to the hippies who lined up for Woodstock and Monterey, this crowd is not bound by the temporal constraints of a “movement.” Their fight has been waged for generations previously, and 40 years later, it must still be fought.

Wattstax is available from Warner Home Video on a Region 1 DVD.