In Looking Back, writer Andreas Stoehr highlights movies from the underexplored grottos of film history.

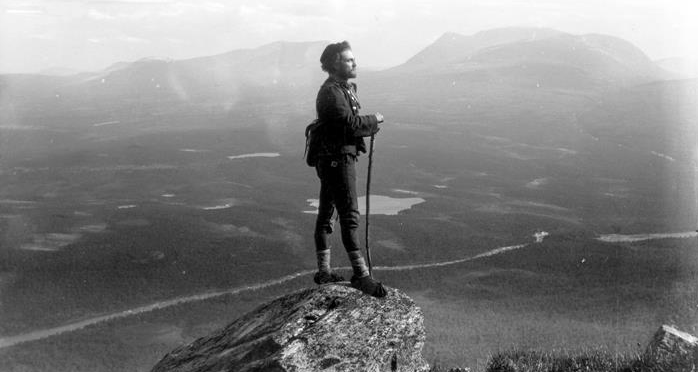

I first learned about Victor Sjöström’s The Outlaw and His Wife (1918) from Kristin Thompson’s list of the 10 best films of 1918. “One of the cinema’s great romances,” she writes. “[T]he natural landscapes… create spectacular backdrops for the action.” This is indeed a film of mountains, rivers, cliffsides, and valleys, with the Swedish countryside standing in for the story’s Icelandic setting. It’s a film of physical exertion, of flights across the hostile wilderness and through the awe-inducing grandeur of Scandinavia. Equally about the bitter cold and the warmth of two joined souls, The Outlaw and His Wife is an intimate two-hander nested within a classic survival narrative.

The two souls in question are the widowed Kalle (Edith Erastoff) and the brooding Ejvind, played by Sjöström himself, who flees his criminal record under the pseudonym “Kári.” All he really wants is solace in Kalle’s rural community, which is instead disrupted by his presence as rumors of his checkered past begin to spread. In a stirring scene that takes up about a fifth of the film’s running time, he details (via flashback) his Valjean-esque experiences with poverty, theft, and a callous justice system. Once his confession is over, she pledges her eternal love.

Now they’re bound to one another, and the rest of the film documents how that relationship may bend or buckle, but will never quite break. The film’s English title is sometimes rendered as You and I, which could hardly be more apt: its subject matter is that “and”—the space between these two people.

The plot unfolds in three parts, each part ending with an overturning of the status quo, a narrowing of film’s scope. In the second of these, Ejvind and Kalle retreat to the seclusion of the hills and raise a child, only to be interrupted by a lecherous old acquaintance and a band of raiders. In the final segment the two of them camp out in the middle of nowhere: freezing, starving, edging toward death and mutual hatred.

As The Outlaw and His Wife’s focus tightens, the strength of the couple’s commitment is repeatedly tested, and repeatedly proven. “Love was the sun in their lives,” explains one tender intertitle. “Their only law was their love,” adds another later on, building up to the film’s chilling final tableau. As in The Phantom Carriage—another great film that he directed, co-wrote, and starred in—Sjöström is weighing decisions and regrets here, doling out moral debt and absolution, then settling on love as the only real means of redemption. It’s through his body, its stark outline against the snowy wilds, and its embrace of Kalle in death that this outlaw finally discovers peace.