Spectres of the past line the halls of Studio Ghibli. The frames of The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, Mami Sunada’s documentary about the studio’s rush to complete Hayao Miyazaki’s 2013 film The Wind Rises, are decorated with them. A sketch of Kiki hovers over an artist’s desk and concept art for Nausicaa rests ominously above the workplace; Kingdom’s contemplative tone renders them not as symbols of past accomplishments, but as totems of the high expectations facing down Miyazaki and his team. Filmed in quiet, reverent close-up, even a plush Totoro takes on a menacing quality, as if challenging his own creator: The next film best be worthy.

Kingdom of Dreams’ primary dramatic conflict is that Miyazaki may not be up to the task. Emotionally distraught, he invites Sunada into his home, where he shows us his meticulously annotated chart of recent disasters – natural, political, and environmental. Without mincing words, he suggests that the end of human civilization seems near to his eyes. (The end-of-days reckoning of films like Princess Mononoke takes on a far more personal appearance as he does.) And Miyazaki has micro concerns to match his macro ones: At 72 years old, he’s finding that his career as an animator has left him unfulfilled, and unsure that he’s contributed anything of worth to the world. Some wondered how The Wind Rises, which concerns an airplane engineer whose life turns tragic when his work is put to wartime means, related to the aging Miyazaki. Hearing him lament an existence spent on commercial causes, Wind reveals itself as no less than a veiled autobiography.

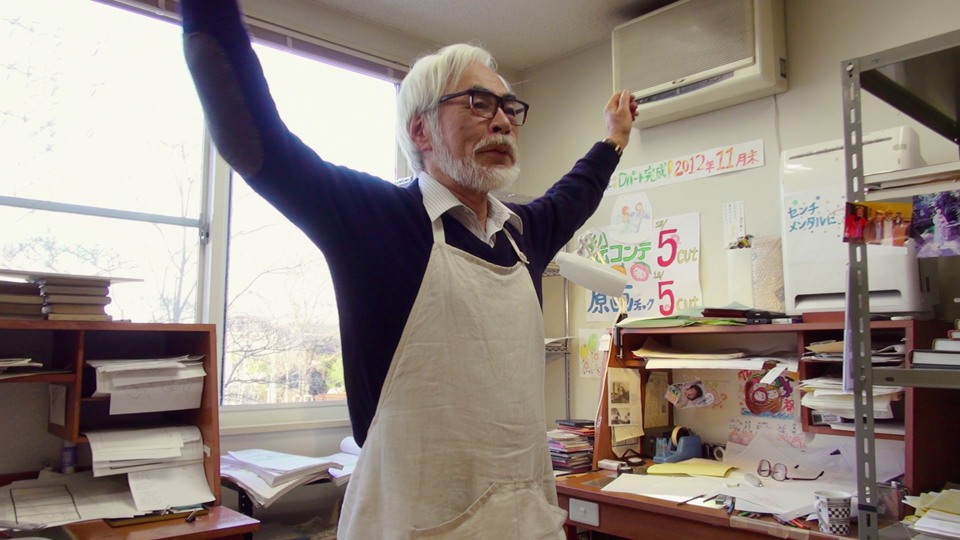

Even Miyazaki’s boundless imagination is facing strife. The Wind Rises is over-budget, behind schedule, and remains incomplete. Miyazaki notes that this is his first film aimed at an audience other than children – and, throughout the production, he fails to find the tone he wants to strike as a result. (Miyazaki’s films don’t have scripts, nor writers: He draws them himself, storyboard-by-storyboard, scene-by-scene, unsure of how his films will end until the endpoint of production itself.) Stress colors each moment. There’s mourning in the air, a melancholic lament for the end of a master’s career – but nobody has time to give in to the dirge, because there’s too much work to be done.

Never content to merely provide a eulogy for Studio Ghibli’s animation house nor for traditional hand-drawn animation in general (both are likely living out their last days) Kingdom instead uses discontinuous editing to track the way production moves from Miyazaki’s sketchpad, to the production team (where the frames are completed) to the post-production team (voice work and editing) to the marketing team (everything from press conferences to posters) and eventually, to audiences. Sunada, rather than follow any one individual’s narrative, documents the stops taken on an idea’s path to the public.

It’s this refusal to kowtow to the cliche of the director’s unquestioned, domineering authorship – suggesting instead that auteurism (Miyazaki’s one-man, one-sketch, one-shot style; the films deeply influenced by his own psychology and doubts) and below-the-line craftsmanship (the workers bringing color and life to those frames, at their own discretion, independent of Miyazaki) are intertwined, co-dependent forces – that propels Kingdom far beyond the ranks of the DVD bonus features it superficially resembles. That Sunada dedicates two scenes to Miyazaki’s son Goru struggling to find the inspiration needed to direct his own next film, confirms her interest in the relationship between a director and his work. Production requires body and soul, her film suggests: the crew the former, the filmmaker the latter.

Kingdom, then – at once a work of documentation, reverence, and filmmaking philosophy – recalls Lillian Ross’ seminal work of long-form journalism, Picture. That book documented the creation of John Huston’s Red Badge of Courage, dedicating chapters to workers above and below the line, providing exposition only when necessary to advance its own chosen narrative; a dramatic structure Sanada translates to the moving image impeccably, providing an impression of the creative process with comparable comprehensiveness. One can only hope Kingdom is afforded a life independent of Ghibli, as Picture has claimed independent of Red Badge’s own legacy. A work this vast – concerning authorship, filmmaking, the hierarchy of the workplace, and the daunting responsibility brought on by one’s own reputation – should not remain a footnote in the Ghibli canon.