“Hello darkness, my old friend”… Rewatching The Graduate is a true time travel. Not only because it’s been almost half a century since Mike Nichols’ cult piece has seen the daylight, during which period fashion and music have changed drastically and Dustin Hoffman is no longer a cuddly boytoy. First and foremost, this classic opens an opportunity to one of those confrontations with a long-gone aesthetic and filmmaking style that remains emblematic to this day, but nowadays is only a stylish point of reference that some filmmakers feel nostalgically inclined towards.

Recently, Schatzberg-inspired Blood Ties director and Frenchman Guillame Canet expressed his fascination with late 60s/early 70s cinema, noting it knew best how to take and cherish its time. It didn’t excuse a lack of dramaturgy with extensive editing aimed at boosting the audience’s reaction and allowed the glance exchange to mold the onscreen mood. He’s not alone in this nostalgic longing for this cinematic style that The Graduate, among many others, represent so well.

Otherwise very enthusiastic, Roger Ebert did not like the “arty camera work to suggest the passage of time between major scenes.” It’s easy to understand his lack of enthusiasm for Robert Surtees’ cinematography; it works beautifully in more creative scenes, with inventively used fade-ins and fast cuts. For example, the famous scene in Elaine’s bedroom, where the viewer sees brief flashes of Mrs. Robinson’s naked breasts as viewed by Benjamin, shocked and paralyzed with shame. Or when we follow the scuba-diving suit scene from Benjamin’s perspective, the camera seeing the ovally cut-out world from under the water through his diving goggles. But the rest of the three-time Oscar-winner’s work here falls flat, especially when imagined without the music, that often fuels the dramaturgy more effectively that the script itself.

Simon and Garfunkel’s famous score might have risen to the top of the charts upon its release and became a landmark cinematic tune, but when The Graduate opened, not everybody was willing to swing their hips to “Mrs Robinson”. Again, Ebert pointed out in his review, that “The film’s only flaw, I believe, is the introduction of limp, wordy Simon and Garfunkel songs.” I couldn’t disagree more: many sequences, evenly paced by recurring shots of Benjamin’s increasingly numb, bored face in a close-up, are long, endless empty shots of content and tension-lacking nothingness, patched up with transparent editing and brought to life only by the energetic tunes. Such literal, illustrative use of music has been a domain of the past for a good while. But in The Graduate, it plays a comparably charismatic and powerhouse part, much like the trans-techno score in Harmony Korine Spring Breakers. Yes, Ebert was right – these songs are wordy. But boy, it worked for the film, and still does so well.

When it opened in 1967, The Graduate was mostly critically applauded for its stand-out performances and the humor, steadily seeping through a seemingly dramatic, socially conscious plot. The quirky, satirical perspective resonates extremely well after all those years. Nichols managed to steer his actors in the right direction, push the envelope, but kept it clean. It now seems like an unreal anecdote, but rumor has it that Nichols originally wanted Doris Day and Robert Redford in the major roles. His final choices, Anne Bancroft and Hoffman, are each portraying a certain cultural archetype, yet, despite the juiciness and literality of their artistic interpretations, never lose the much-needed credibility.

Mrs Robinson is a plotting, strategizing man-eater who, vamped up just a bit, could easily become a graphic novel heroine in the next “Sin City” installment. However, the the psychological underpinning grounds her, furnishing the perfect cougar/femme fatale with deeply human traces of frustration, disappointment, loneliness, and bitterness so recognizable for all the formerly romantic cynics. Katharine Ross’s Elaine seems to be originally planned more as a beautiful prop, a bargaining chip greedily torn apart by her demonic mother and frantic suitor in this semi-incestuous clinch. But there’s a timeless girly honesty and pureness to the character that allows her to stay adequate, many of her likes still appearing in the contemporary films. She’s also not devoid of personality and an interesting case of a daughter-figure more sexually repressed than her mother.

Finally Benjamin, by many then-reviewers deemed an “annoying”, “unlikeable tool.” Somehow this figure seems to be the most timeless and, definitely, less annoying to the 29-year old me than a 17-year old who saw Nichols film 12 years ago for the first time. Ben is privileged and lost. Boredom was something he could’ve afforded with his parents’ thick wallet and position. His ideas about life and his desires were not carefully fostered, conscious concepts. This ill-willed, expected adult is inertly floating in the pool of coincidental meetings and impulses, being an agreeable prop in fate’s hands. His only genuine emotion is irritation – he’s childishly rebelling against expectations and pressure.

Benjamin is most comfortable in the previously mentioned scuba diving scene. He sits on the bottom of the pool, awkwardly alone and muted, after being forced to parade for a loud bunch of his parents’ neighbors, like a sad polar bear in a zoo. This golden boy is in fact grey-ish, dull, and full of fear. Fearing the inescapable obligation to man up and devoid of his own ideas to shape the future, he falls for the similar trap his nemesis Mrs Robinson did, attempting to desperately fit into social schemes and patterns before actually finding out his true self, confusing fascination for a lifelong commitment. They say timelessness is a key in becoming a classic. Doesn’t it all ring a strangely familiar bell in the times when youth is burdened with too many choices?

It seems the the public’s enthusiasm (the film was one of the highest-grossing blockbusters of its time) in a way deflected a more complex understanding of the film’s point of view. The Graduate is much closer to a thoughtfully plotted satire than simply a cool, sexy, counter-cultural piece cut out to excite rebellious youth hungry for controversy – a group that responded to it so well at the time. It provides laughter but requires focus, begging kindly not to let the most poignant, yet least redundant moments – like the last seconds of the finale – slip the audience’s attention.

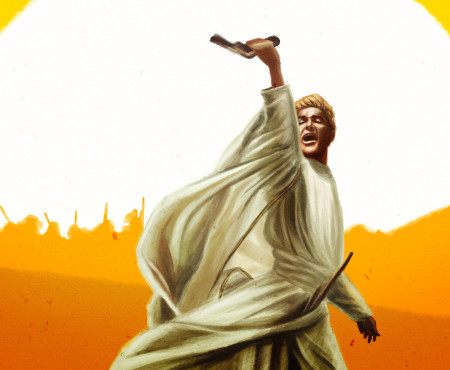

Note: If you dig the original illustration above, check out Alexandra Kittle on her Etsy page and follow her on Twitter here.