Editor’s note: Annie Hall is one of the 10 best films of the 1970s voted on by staff, friends, and readers of Movie Mezzanine. For the sake of surprise, we’ll wait to reveal where this and every other film ranks on the list until the very end. We hope you enjoy.

…

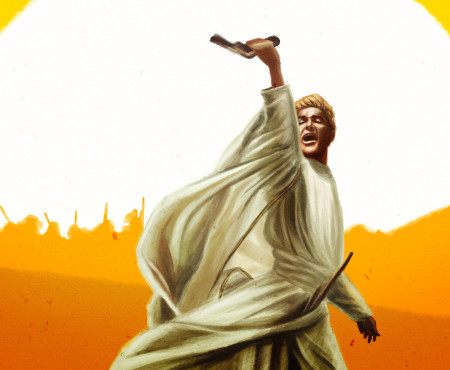

The lasting American classics of the 1970s weren’t so much released as they were unleashed. They’re a foaming, vicious bunch of savages that still blaze across screens and shake viewers to their core today. The work of directors Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Stanley Kubrick, John Cassavetes, William Friedkin and Sidney Lumet helped set a new standard for cinematic rules by continually bending and breaking them. They provide unflinching glimpses into the lives of reprehensible protagonists. They aggressively and exhilaratingly challenge an audience’s comfort, safety and trust that had been built by decades of more restrained filmmaking. Much of this burst of incendiary cinema was due to the influence of foreign directors who’d been remolding the medium overseas for years, but had yet to mingle with the mainstream in the States until this pioneering decade in cinema rebranding.

What’s unique about this period is how many risks filmmakers took and were allowed to take. It smacks of an era gone by, when audiences and studios had different wants and agendas, and directors were encouraged to plumb depths to whatever extent they saw fit. A common adage is, “They don’t make them like they used to”, to which there is some truth, of course. There are still iconic, envelope-pushing, rule-changing films being released today, but in much different regard from those from over 30 years ago. Looking back, some films are so brazen, so electrifying, and so vital, it’s a surprise and a relief they ever got made at all. None more so than Woody Allen’s reigning romantic comedy bedrock, Annie Hall.

Annie Hall as we know it today was never meant to be. Yet it plays pristinely, a prime lean cut pitched to perfection in which no scene, shot or conversation is a second too long or too short. Its serpentine stream-of-consciousness non-linear narrative conceit is seamlessly integrated, never betraying the emotional integrity of its characters or the central romance. It’s a film that combines so many idiosyncrasies and technical innovations, yet remains so fundamental in its representation of a couple throughout its many stages of growth, resulting in the single most universal film of all time. And it was all by accident.

Until Annie Hall, the films to Woody’s credit had been exclusively slapstick, zany comedies, all descendents of the likes of Bob Hope and the Marx Brothers, and precursors to the absurdity of Airplane! and its ilk. While not tremendous moneymakers, Woody’s pre-Annie Hall comedies were successful in leaving the mark of his comic sensibility on audiences, and doubled as ideal vehicles for a bevy of hilarious heroines in well-drawn roles including Louise Lasser, Jessica Harper and Diane Keaton. After skewing Russian literature (Love and Death), political leaders (Bananas), and future nostalgia (Sleeper) in broad comedies, it was as if Woody said, “Okay, you’ve seen that I can be funny, now it’s time to get to know me a little bit.” So he set out to make his first film set entirely in modern-day New York City, about what he refers to as “real” people.

The most universal film of all time needed a conduit. Perhaps an unlikely candidate, that hat fell on the head of Allen, the nebbish, bespectacled, perennial standup comedian who, even after releasing a film a year since the mid-1960s, never wore the job description of ‘filmmaker’ conventionally. Many of his films unfold like routines. Some are episodic (Radio Days, Everyone Says I Love You, Deconstructing Harry), while some play like protracted bits (The Purple Rose of Cairo, Zelig, Midnight in Paris). But all benefit from his extensive literary and cinematic knowledge and gift of peerless comedic timing to flesh out each story in a satisfying way during its transition to the screen. The romance between Alvy Singer (Allen) and Annie (Keaton) that propels Annie Hall was only a small part of Woody’s original vision, but so prevailed in audiences’ favor during the editing and screening process that he decided to reduce the film to the two of them and leave the rest, begrudgingly, behind. It’s the best, most selfless decision he could have made.

Early drafts of the film centered around a murder mystery of a college professor who lived in the same building as Alvy and Annie, which then devolved into a farcical period piece set in Victorian England. Woody had previously decided in 1975 after making Love and Death in France and Yugoslavia never to shoot outside New York again, so that idea was quickly scrapped. The script, co-written by Marshall Brickman, then became “Anhedonia”, which means the inability to experience pleasure, a probing glimpse into the mind of a man who suffers from that very condition. Plenty of outlandish fantastical components remain, such as Alvy’s flashback to an elementary school classroom in which present day Alvy interacts with his former classmates, asking them where they are today (“I used to be a heroin addict, now I’m a methadone addict,” says one cherub faced first grader). One of the more famous sequences that was omitted involved Alvy playing basketball with the New York Knicks, shot on the court with the actual team. By eliminating these elements – the ones that restrict the narrative to Alvy’s mind – and filtering them instead through the core relationship with Annie, the film reaches wide enough to embrace any and all who have met someone who altered the course of their lives forever.

Alvy and Annie’s relationship isn’t one for the ages, but that’s precisely what makes it so compelling – it’s utterly authentic. Of course their relationship is doomed. There’s no hope that love will conquer all, or anything so remotely fanciful. In fact, they’re broken up even before the film begins.

After titles set to no music, with only ambient scratches and pops on the soundtrack, Annie Hall begins with Alvy, who makes his living as a comedian, addressing the camera in what is essentially a one-on-one standup routine with the audience. “There’s an old joke…” he says, and so begins his confessional. He and Annie have broken up and he is suffering. Then, in an attempt to discover what went wrong, he launches into the details of his life, beginning with his unusual childhood, through to his first marriages and then meeting and falling in love with Annie. Even after countless viewings of Annie Hall, the dead silence over the opening titles is still jarring, but it’s the perfect gateway. It sets no expectations, makes no assumptions. It’s spare and unobtrusive, and lets the film that follows speak for itself.

That “where-did-I-go-wrong?” moment at the top of the film that slingshots the story into motion is as close to a plot as the film ever has, but Woody deftly manages to implement his snappy train of thought without it ever derailing. Characters could be speaking directly to the camera, then in the next scene interacting with their younger selves, and then in the next scene they could be animated in the style of a Disney cartoon, yet Woody makes it all seem like the most natural progression possible.

The unsung hero of Annie Hall (and Manhattan too, for that matter) is co-writer Brickman. Woody always wrote screenplays on his own (as a time saver), but Brickman was invaluable in aiding the scripts with their sparkling back and forth. He and Woody would venture out to the streets to bounce ideas off each other and to chat, in what became the repartee between Alvy and his womanizing friend Rob (Tony Roberts), who calls Alvy “Max” because he deems it a better name for him. Brickman was the one who, along with editor Ralph Rosenblum (who had worked with Woody since his first film Take the Money and Run in 1969) spoke up about the original cut of Annie Hall being incomprehensible and in desperate need of reworking.

The irony is that Woody came full circle with Annie Hall. His somewhat narcissistic downbeat intent didn’t transpire to the final product, but 36 years and over 40 films later, Annie Hall is still his legacy. It’s the Woody Allen film that people who dislike Woody Allen like. It’s his most famous film, his most cherished, and his most awarded (in 1977, it won Oscars for Best Screenplay, Director, Actress and Picture over the big box office draw that year, Star Wars). But it’s his relinquishing the limelight to his character’s relationship with Annie that ensured its timeless canonization.

When they first meet after a group tennis match, Annie’s a giggling mess as she offers Alvy a ride home, and then turns out to be the worst driver he’s ever seen. (“That’s okay, we can walk to the curb from here,” he says after she finally parks.) Their impromptu day date continues to her back patio where they drink wine and struggle to keep their conversation interesting. Neither is listening to the other, as demonstrated by the subtitles that pop up providing their inner monologues in which both are actively worrying about how they’re coming off to the other. By the end of their relationship, Annie is more grown up, more assured, more confident, which were all destinations led to by Alvy’s influence. It’s perhaps the harshest realization, that you can help your partner to outgrow you.

It’s common for Woody Allen’s films to be dismissed by gentiles (non-Jews) who feel they have no entry point into that world or sense of humor, perhaps feeling left out by what they see as inside jokes, or maybe unsure about whether they should feel comfortable laughing at rather than with a person of Judaism (as someone who was brought up Jewish, I can assure those people, yes, they absolutely should). But Woody never relies on playing up the stereotypes of Jews for cheap laughs. In fact, he usually skews others’ perception of Jews. When Annie first meets Alvy, she blurts out a comment she should probably instantly regret, but tellingly doesn’t. “You’re what Grammy Hall would call a real Jew”, she says. Later, when Alvy meets Annie’s family, they’re sitting around the dinner table and the Jew-hating minx at the end of the table takes one glance at Alvy before he is physically transformed into a full-bearded rabbi. The scene culminates with Annie’s family’s civil congregation interacting through a split screen with the shrill, howling barbarism of Alvy’s parents at their dinner table (Alvy’s mother repeatedly hollering, “His wife has diabetes!” is so hysterical and quotable, it should be ringtone fodder). Woody isn’t making any overarching statement about Jews or even about WASPy families like Annie’s; he’s providing them as examples of polar opposites, how one fits like a square peg in a round hole into another’s life, and how a romantic pairing doesn’t necessarily make sense in the many different contexts of the individual’s lives.

This dual polarity is accentuated by Annie and Alvy’s bicoastal desires. She is drawn to the sunny, laid-back charm of Los Angeles, while he remains affixed to New York City, a factor that ultimately, physically separates them. But not before a visit to the nonstop party home of record producer Tony Lacey (Paul Simon), where a dashing young Jeff Goldblum almost steals the entire movie with his one unforgettable line of dialogue.

It’s a testament to the timelessness of Annie Hall that most of its references to pop culture or current events are unsuccessful in dating the film. Almost 40 years later, it’s unlikely that today’s audiences would recognize famed media theorist Marshall McLuhan when Alvy pulls him out from behind a poster at a movie theatre to lambast a loudmouthed moviegoer for his misguided and pointless pontificating on Federico Fellini, Samuel Beckett and McLuhan, but the gag has never lost its punch. It’s still the most victorious, cheer-worthy scene in the entire film. A standalone masterpiece of comic-fantasy indulgence punctuated with a line of dialogue that bittersweetly sums up not just Annie Hall, not even just Woody Allen’s repertoire, but cinema as a whole. Alvy, standing between McLuhan and the shamed movie-line nuisance, turns to the camera and laments, “Boy, if life were only like this.”