Editor’s note: Alien is one of the 10 best films of the 1970s voted on by staff, friends, and readers of Movie Mezzanine. For the sake of surprise, we’ll wait to reveal where this and every other film ranks on the list until the very end. We hope you enjoy.

…

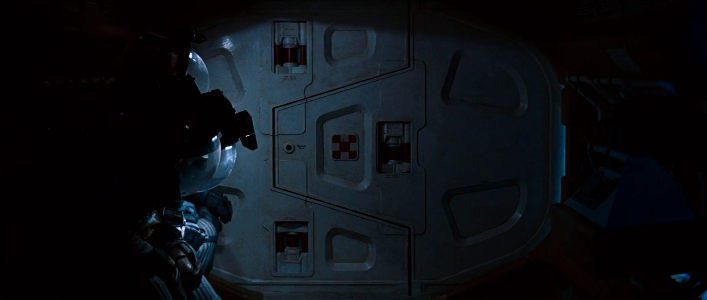

Alien brought with it a style of lighting and production design that gave walls, ceilings and floors the tactile quality of flesh. Director Ridley Scott and cinematographer Derek Vanlint achieved this look by pointing their cameras in the direction of hard light sources rather than keeping them hidden or tamped down. Between the light and the camera, enrobed with claustrophobic, low-ceilinged sets, Scott placed the film’s humans, often modeling their faces in trenchant chiaroscuro or faint fill light. Smoke, steam and sparks provided intense accents.

It’s a look thousands of films, commercials and TV shows have imitated since but very few have carried out with such elegance or dramatic weight. The design team assembled by writer Dan O’Bannon emphasized realism and functionality aboard the ship (Ron Cobb, Chris Foss) while evoking a medieval nightmare in anything to do with the alien and its planet (H.R. Giger). Scott’s patient observation of events makes the film as terrifying as it is beautiful. He trusted the actors he cast as bickering working class crewmembers to hold our attention while the alien threat menaced from offscreen, and each shot is its own universe of primal tensions and pleasures.

So much has been written about how many of the film’s iconic images evoke those tensions and pleasures (symbolic wombs, tombs and genitalia) that I prefer to sample here some of the less celebrated transitory moments that prime them:

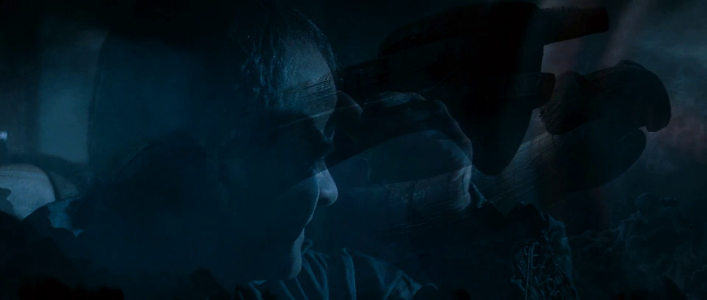

After a rough landing that starts a small fire and knocks out the ship’s power, the film briefly becomes something like a documentary. A handheld camera darts around, capturing the crew scrambling to put out the flames and restore power. Kane (John Hurt) is thrown into shadow as a lamp shows us just how cramped the cabin can get.

Lambert (Veronica Cartwright) is the film’s barometer of terror, and without histrionics or excessive dialogue, Scott indicates how desperate the situation has gotten just by isolating her from the dark background with pearly light that brings out her startled teal eyes.

Just before the fateful excursion that will bring the alien on board the ship, there is a moment that could pass for penance in a shadowy cathedral.

Ridley is Queen of the ship long before the death of her superior, Dallas. We know this only by the reverent compositions.

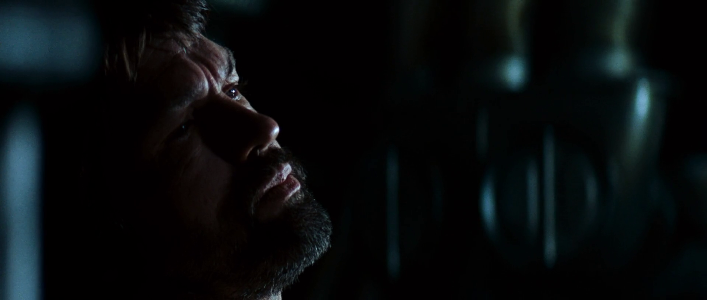

Dallas (Tom Skerrit) spends the film looking beleaguered and irritable. Whether stealing a moment to himself in the escape shuttle cabin or leading a fateful expedition, he is quietly losing his grip.

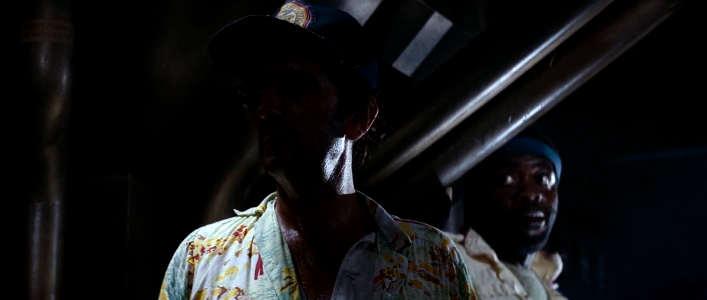

Parker (Yaphet Kotto) and Brett (Harry Dean Stanton) are second only to the alien itself when it comes to sketchy lighting. They are highly skilled engineers, but in the film’s social microcosm they’re more like boiler room mechanics.

They become real to us as their desperation surges.

Ash is not to be trusted, according to one of the strangest, longest shots in the film: We explore the infirmary in a smooth arc until resting on Ash, who is studying the alien through his microscope. Ridley startles him and us, appearing seemingly out of nowhere to subtly interrogate him.

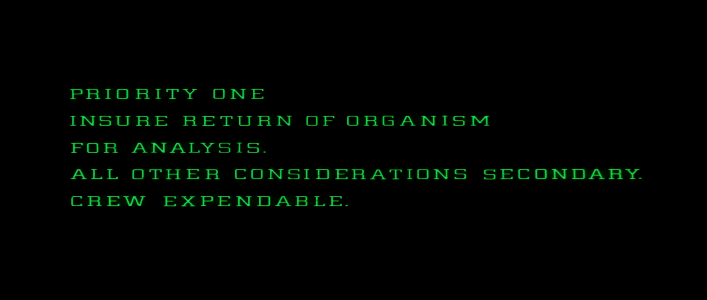

We eventually learn that Ash, along with the corporation that every member of the Nostromo crew works for, has no concern for their survival, only for the alien’s safe transport to laboratories back on Earth. In 1979, capping a decade of post-60’s disillusionment, inflation, and Hollywood’s unprecedented (if mostly superficial) interest in working class struggle, this film was a disquieting statement. “No one can hear you scream” is a possibility that haunts corporate wage slaves to this day. Alien has extraordinarily long reach into an unspeakably savage animal past and a mercenary future that is actually right now.