I came to Federico Fellini’s 8½ late, but not for lack of trying.

As a dutiful student of Roger Ebert’s Movie Home Companion — in those antediluvian pre-Internet days the annual installments were bestowed upon me as a Christmas gift every year, then I’d spend the rest of the holiday ignoring my family while reading – I understood 8½ to be a masterpiece. Roger and everybody else said it was one of the all-time greats, therefore it must be. But I just didn’t get it, goddammit.

Time and again back in high school, I would rent a blurrily-transferred, poorly dubbed VHS copy from my local, pre-Blockbuster Mom and Pop video store, yet always returned the tape more flummoxed than enthralled. The whole thing was awfully bloody long and just so rangy, so diffuse — so *foreign.* By the time I entered New York University Film School as a smarter-than-you teenager, my contrarian punk-rock stance on pretty much every topic had hardened to a point where I was loudly proclaiming that Woody Allen’s Stardust Memories was actually a better version of 8½ than Fellini’s 8½.

In retrospect, this probably sounds insane. But in defense of my younger asshole self, please remember that at the time, having grown up on Allen’s films I already possessed the framework of knowledge necessary for appreciating how a beloved screen persona had borrowed Fellini’s themes and techniques for his own ends. And I still do consider it a great feat in filmmaking “cover songs” – one of the only times I’ve seen a director so brazenly remake somebody else’s film while still making it feel like one of his own.

I also liked Stardust Memories more because everybody else seemed to hate Stardust Memories, and I was (is) a contrarian dickhead know-it-all. And then I always did fall for (still do) women as crazy as Charlotte Rampling’s Dorrie. But that’s another story.

Cut to NYU in the mid 1990’s. I’m in a Directing class taught by Antonio Monda. On the odd chance you are one of the few people in New York City who has not yet had the pleasure of Antonio’s company, please let me explain that this local celebrity is a sly, gregarious Italian gentleman straight out of the Algonquin roundtable who at a very pivotal moment in my life did me the enormous kindness of calling me out on all the bullshit I’d been happily skating by with up until that semester.

No teacher ever pushed me harder or encouraged me more, and we’ve been dear friends ever since.

During the lecture portion of our class, Antonio showed just two scenes from 8½ – the “Asa Nisi Masa” sequence and then the final parade. I’m sure I probably groaned and said something stupid, and I’m sure he put me right back in my place with one of his usual withering one-liners. (“Sean, disappear from my life,” was a perennial.) But as he talked us all through the scenes, calling attention to the way themes were expressed in the framing and the sound design, it was like – to quote the Cape Cod weather report — light dawning on Marblehead. I finally understood 8½.

Now I’m not saying that you need a sardonic Italian interpreter to understand this movie (though Antonio’s commentary is helpfully included on the Criterion DVD if you would like to spend a couple of hours with my friend) but I am saying that sometimes these Great Films enshrined on lists like this one run a risk of being calcified by hyperbolic praise and the weight of legend, to a point where they begin to feel more like obligations. You’re going to church instead of watching a movie, as I was every time I rented this one as a teen.

Now I’m not saying that you need a sardonic Italian interpreter to understand this movie (though Antonio’s commentary is helpfully included on the Criterion DVD if you would like to spend a couple of hours with my friend) but I am saying that sometimes these Great Films enshrined on lists like this one run a risk of being calcified by hyperbolic praise and the weight of legend, to a point where they begin to feel more like obligations. You’re going to church instead of watching a movie, as I was every time I rented this one as a teen.

So let’s just get it out there right now that 8½ is seriously funny.

Fellini, reeling and stumped after the massive international success of La Dolce Vita, abandoned his Italian neo-realist roots for good and presents here one of the more amusingly self-lacerating self-portraits in the history of cinema. He’s not just gazing at his navel, he’s laughing at what he finds in there.

Marcello Mastroianni is back serving as the filmmaker’s stand in, this time playing Guido Anselmi, a renowned movie director who’s suffering from a paralytic mid-life crisis and has run out of things to say. He’s already signed on to make a massively budgeted science fiction picture, and though he talks a good game, Guido hasn’t quite figured out what the movie is going to be about just yet.

Attempting to hide out at a spa, he’s dogged in every scene by producers, screenwriters, fans, critics, mistresses, his wife and most of all memories and fantasies – into which Fellini’s film slips without a moment’s notice. Guido’s background mirrors the filmmaker’s, as do his lady problems. But it’s a funhouse mirror, presented in the groundbreaking cinematography of Gianna di Venazo who startlingly, constantly has people rudely entering the foreground of the frame like absurd interruptions. The sound drops in and out, sometimes mid-sentence depending on the character’s mood.

Guido frets and fritters, meeting several times with a Cardinal and a Cardinale – the latter an opaque ideal of unattainable beauty played by maybe the only actress in the world fit for such a role. Then he dithers. He screws his annoying mistress and hides from his financiers, drifting away mid-conversation into baroque childhood reveries, mostly sexual in nature. The entire time, hundreds labor away at building the set for his latest (still unwritten) opus upon a nearby beach – a giant phallic spaceship that’s going nowhere. Yes, the central metaphor here is an enormous, useless cock.

I don’t mean to imply that the entire movie is a piss-take, but after so many viewings I’ve come around to the idea that 8½ is at least half-kidding, most of the time. Mastroainni is such a mischievous screen presence, one need only take a brief look at Daniel Day-Lewis (inarguably a better actor who happens to be all wrong for the role) as Guido in the recent woebegotten musical adaptation Nine to see what a vapid pit of angsty self-pity into which this all could have descended. But instead it is a playful nervous breakdown, alight with ideas and joy, bouncing about to Nino Rota’s improbably catchy soundtrack as Guido gets his comeuppance.

(Briefly circling back to the previous paragraph, I still don’t understand why on Earth anybody thought a musical version of 8½ needed to exist when we already have All That Jazz.)

Fellini gets a bad rap sometimes for his leering camera and, to this viewer, a not unpleasing fixation on big boobs and bigger butts. But watching this film again the other night, I was fascinated by his treatment of Claudia Cardinale. For two hours she has been an unattainable embodiment of female perfection visiting Guido only in dreams – she’s his imaginary, idealized cure for all that ails him. Then when she finally shows up for real, they don’t hit it off at all. This is expressed beautifully in the blocking and camerawork. He’s standing up while she’s sitting down, he’s in the shadows while she’s in the light. They’re two of the most beautiful people ever photographed, not striking a single spark.

Fellini gets a bad rap sometimes for his leering camera and, to this viewer, a not unpleasing fixation on big boobs and bigger butts. But watching this film again the other night, I was fascinated by his treatment of Claudia Cardinale. For two hours she has been an unattainable embodiment of female perfection visiting Guido only in dreams – she’s his imaginary, idealized cure for all that ails him. Then when she finally shows up for real, they don’t hit it off at all. This is expressed beautifully in the blocking and camerawork. He’s standing up while she’s sitting down, he’s in the shadows while she’s in the light. They’re two of the most beautiful people ever photographed, not striking a single spark.

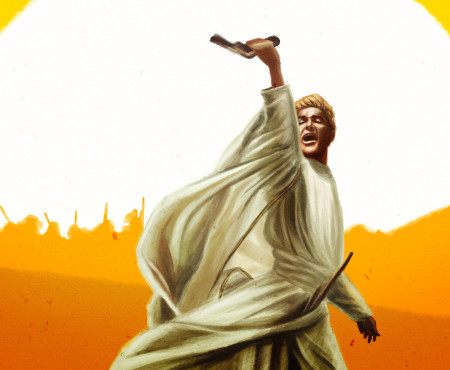

Guido causes all of his own problems and reaps what he sows, but it is only at the very end, when he stops trying to bullshit around (directing everything?) and embraces the chaos he’s created, then the character can finally find a measure of peace. That’s when the circus begins. Life is a carnival.

8½ is not actually my favorite Fellini movie, just because La Dolce Vita cuts me to my core. But I still love it because it reminds me that I don’t always understand everything on the first try. I love it because it’s so silly and inventive, and I love it because that “Ride of the Valkyries” music cue always makes me laugh like a drain.

But I mostly love 8½ because it reminds me how a good teacher can help you see things that you were missing before. Grazi, Antonio.