There’s a very good chance that Denis Villeneuve is just fucking with all of us.

His newest film Enemy opens with the cryptic quote “Chaos is order yet undeciphered,” from the José Saramago novel which its based on, The Double, and then gives us an erotic yet disquieting dream sequence in which protagonist Adam Bell (Jake Gyllenhaal) checks into an Eyes Wide Shut style strip club that has a strange fetish for spiders crawling along the dancers. For a while, you’re unsure just what you’re going to get from this film — even if you do know the initial premise. Will this be a pretentious aping of Lynchian dream-logic, or will it reward the viewer with its strange imagery.

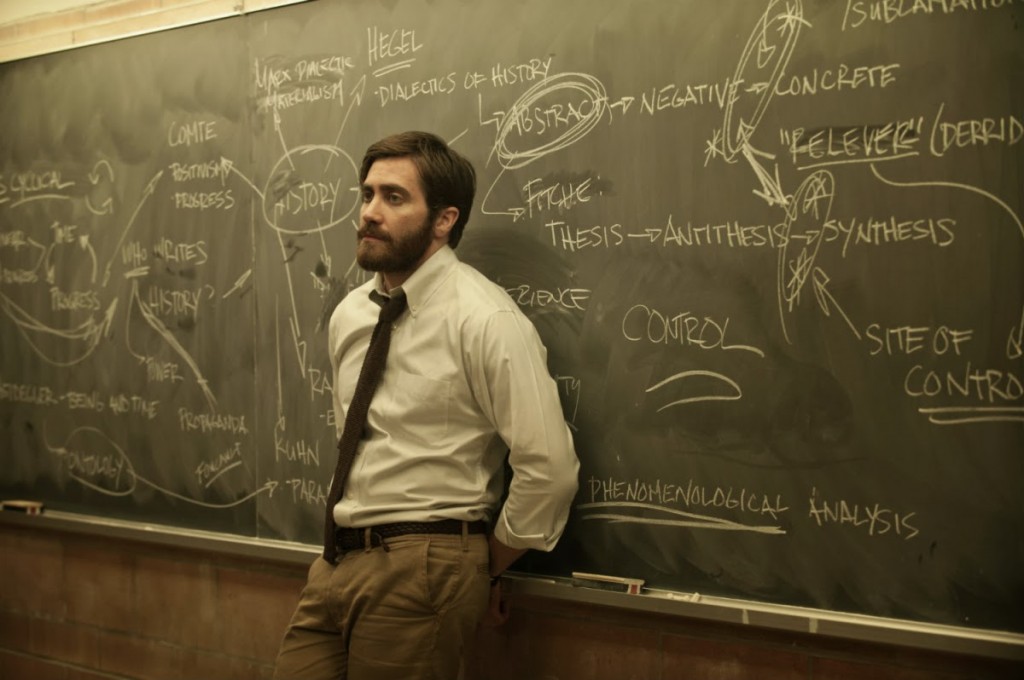

I’m still not sure if the film really is as intellectually stimulating as it thinks it is, but I’ll be damned if it isn’t one of the most absorbing psychological thrillers I’ve seen in a while. Owing just as much to Cronenberg as he does to Lynch — with the film’s Canadian backdrop, sickly color palette, sexual perversion, and strange fascination with insects and themes regarding the distinction between body and mind — Villeneuve glues us to history professor Adam Bell’s existential predicament: meeting an exact physical doppelganger named Anthony (also Gyllenhaal), a Z-list movie actor who is either everything Adam is or is not, depending on how you look at it.

Gyllenhaal plays both Adam and Anthony with masculine anguish and quiet, existential horror. While it’s easy to reduce his performance by claiming he’s just doing a whole lot of brooding, he manages a rather difficult balancing act in emphasizing both how different and alike the two men are.

It’s easy to see that Adam is very reserved, serious, and intense, while Anthony is more outgoing, active, and flippant; and as simple as that dichotomy sounds on paper, Gyllenhaal manages to imbue each personality with enough subtle differences to outweigh the obvious ones. At the same time, what really makes Gyllenhaal a highlight is how he utilizes the traits that connect both Adam and Anthony. Neither one feels like the “hero” or (pun not intended) the “enemy”. Rather, he does the simple but noble option: treats them both as flawed human beings who wind up doing drastic things when faced with something that extends our limited understanding of how the universe operates.

Enemy‘s supporting cast is also very good, if mostly under-utilized. Isabella Rossellini (of Blue Velvet fame) is given only one scene to really chew, but boy can she chew. Melanie Laurent plays Adam’s girlfriend, who is only used for cold, dispassionate sex by both Adam and, sadly, the film. Not given much to do, you’re left wondering why Villeneuve and co. hired an actress as talented as Laurent for such a thankless role. The only supporting player who really gets to shine is Sarah Gadon (further drawing comparisons to Cronenberg), who imbues a small role — in her case, Anthony’s pregnant wife — with incredible weight and dimension, able to make the most out of her scenes with an expressive face that can display roughly 346 different types of terror of the creeping unknown.

This is obviously not the first time we’ve had a film about doppelgangers — see Kieslowski’s wondrous The Double Life of Veronique, Ingmar Bergman’s masterpiece Persona, hell, there’s even a new one coming out later this year from Richard Ayoade called The Double, not to be confused with the Saramago novel that Enemy is based on — but Enemy really hones in on the existential dread of what it would be like to meet your double in a way that Ayoade’s comedic sensibilities, the sensitive humanism of Kieslowski, and the enigmatic qualities of Bergman couldn’t.

That isn’t to say that Enemy is lacking in mystery, beauty, or (very dark) humor. If anything, the screenplay by Javier Gullón features a fatal weakness in thinking that the mystery behind Adam and Anthony’s circumstances can even be solved, leaving brief but still rather noticeable “clues” for attentive viewers to discover through repeat viewings.

Thankfully, Villeneuve recognizes these faults, and while he still rolls with them, his atmosphere is so exhaustively, oppressively grim that the rest of the film carries with it an ironic quality. Villeneuve isn’t treating his story seriously in the same sense that he treated Prisoners. Rather, his style is invasive, omnipotent, and voyeuristic as he just observes these puny humans as they’re undergoing a cosmic anomaly that’s beyond human comprehension, occasionally burning them with a giant magnifying glass just to see what happens. As moody as the film is, it’s clear he’s having some sadistic fun with the material.

Another apparent influence of Enemy is Hitchcock, especially in its masterful pacing. Wading through its plot in a slow, limping, groggy demeanor, many scenes are simply just characters stalking and following each other — recalling Hitchcock’s Vertigo, among his other films. Villeneuve manages to imbue these seemingly simple scenes not just with gracefully wrought tension but also a surprising amount of emotion and existential foreboding all with just colors, shot choices, and the actor’s faces.

All of this culminates to, yes, that ending that all the other critics won’t stop yammering about. Is it, as David Ehrlich said, one of the scariest movie endings since Don’t Look Now? It’s hard to say at this point, but it’s been exactly a month since I’ve seen the film and it still hasn’t let go of my imagination. There’s a very good chance that the final shot — which basically begs the audience to “interpret” it — means absolutely nothing in the grand scheme of things, but that’s nothing compared to the sheer visceral impact it had on me.

Just like the two Gyllenhaals uncertain of whether or not their existence even has a function in the web of organized chaos that makes up the fabric of our universe, we can’t help but refuse to ignore the experience, digging deeper and deeper into the horrors that await us. And who knows, maybe there is true meaning buried underneath. I couldn’t tell, though. I was too busy running from the spiders.